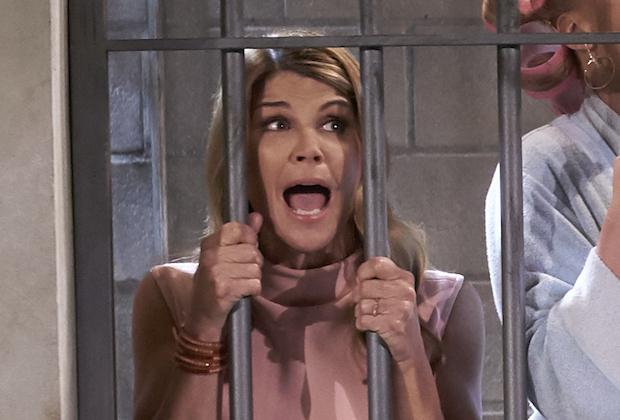

March 12, 2019 was a hard day for fans of Full House and the American meritocracy. Lori Loughlin, Aunt Becky of the aforementioned beloved sitcom, and her husband Mossimo Giannulli were charged by federal prosecutors in a scheme to secure positions for their children at the University of Southern California (USC). The couple allegedly paid $500,000 to William Singer, owner of a college counselling business and an additional $50,000 as a bribe to a coach at USC. Loughlin and Giannulli worked with Singer to convince the admissions office that their daughter Olivia Jade, a YouTube star, was a crew coxswain, going so far as to stage a photoshoot with Olivia and a rowing machine. The duo were far from the only people implicated in the scandal. Along with Singer, Loughlin and Giannulli, 33 other parents and various college athletic coaches were indicted. Between 2011 and 2018, these parents paid Singer a total of $25 million to get their children into elite colleges. Singer’s college corruption services (all items sold separately, terms and conditions apply) involved bribing athletic coaches and fixing SAT scores. The former called for doctored photos and falsified athletic achievements while the latter entailed acquiring disability waivers for extra time, bribing proctors and changing scores post-test.

For many, the scandal was simply further confirmation that the college admissions process unfairly advantages wealthy white applicants. So why would people at the top of the economic ladder hijack a system that already works in their favor? Michael W. Kraus, a social psychologist at Yale, and Paul Piff, a psychology professor at the University of California Irvine, suggest the answer lies in the myth of the American meritocracy. According to Piff, the narrative that rich people have worked for everything they have and deserve all their wealth is “baked into the American dream.” It allows people to believe that if they keep their heads down and work hard they too can reach the high echelons of society.

Michael Kraus points to the importance of elite colleges in maintaining this myth. The elite may be rich now, but if their children cannot achieve the same level of status, it suggests that their achievements were perhaps a fluke or the result of institutional privilege rather than genuine merit. Parents like Loughlin and Giannulli try to rig the system precisely because they need it to continue unfairly stacking the cards in their favor.

Perhaps more startling than the scandal itself are ways in which the college admissions process is implicitly and legally racialized. For one, low-income students of color are often faced with many more obstacles than middle-class and wealthy students. According to Vox, many low-income students have to deal with the stress that comes with poverty and rarely partake in the expensive prep-classes, tutors and extracurriculars that their wealthier peers benefit from. More troubling is the use of legacy status and donations to further advantage white wealthy students. It was recently revealed that a legacy student is five times more likely to get into Harvard than other students. The university also maintains a list of applicants whose family members are donors. According to Vox, 42 percent of the students off this list are accepted to Harvard, a sharp contrast to the general admissions rate of 4.6 percent in 2018.

First generation students, many of whom are low-income, are neither able to donate large sums of money nor claim legacy status. Elite schools are therefore well-versed in creating socially acceptable ways to privilege wealthy students and further perpetuate the myth of a meritocracy. Before pointing a finger at the 33 indicted parents as an appalling exception, there is an urgent need for colleges to take a good hard look at the ways in which they already privilege some students over others.

The flaws in the college admissions process are particularly striking considering the narratives surrounding low-income students of color. These students are no strangers to the whispers that follow them around campus, to the voices that suggest that their places at elite institutions are unfairly earned because of their minority status or because of policies like affirmative action. In reality however, as Vox points out, the Supreme Court only allows colleges to admit a student via affirmative action if that student will “educationally benefit all students on campus by creating a racially diverse environment.” There is no such requirement for legacy students. As we continue to grapple with the implications of the college admissions scandal, even at Wellesley (where 14 percent of the Class of 2021 was legacy), perhaps we are better suited asking ourselves how we expect low-income students of color to perform on an even playing field when wealthy students are not even asked to play the same game.

Alexa | Apr 3, 2019 at 4:07 pm

Really eye-opening about the impact of the meritocracy. Well written!!