Founded just over a year ago, Wellesley Against Mass Incarceration (WAMI) recently finished a major campaign: the campaign to stop calling campus police. Now they are gearing up for their next campaign, aimed at asking Wellesley’s administration to divest from private prisons.

Clearly, Wellesley Against Mass Incarceration involves a variety of projects. However, this broad span has a common theme: opposing the prison-industrial complex. In addition to the campus police campaign and the upcoming divestment campaign, WAMI has had several events in conjunction with Black and Pink, a Boston-based organization that focuses on helping incarcerated LGBT people, as well as bringing speakers to campus.

Most of WAMI’s members, including a solid number of underclassmen, joined the organization because of their interest not just in individual campaigns, but because of their interest in the organization’s mission.

“When I came to college, I knew that I wanted to do something with organizing on a larger scale,” said member Jenna Ocheltree ’22. “We have a couple different activist orgs here on campus, but WAMI seemed really important to me because it isn’t just one isolated issue. It feeds into so many other issues with racism and classism and the drug war. It’s also very emblematic of the whole corruption in our political system.”

“The name is pretty straightforward,” added Felix Jordan ’22, who is the organization’s secretary. “This is something I was interested in, so I just kind of went to the meetings, and I kept going.”

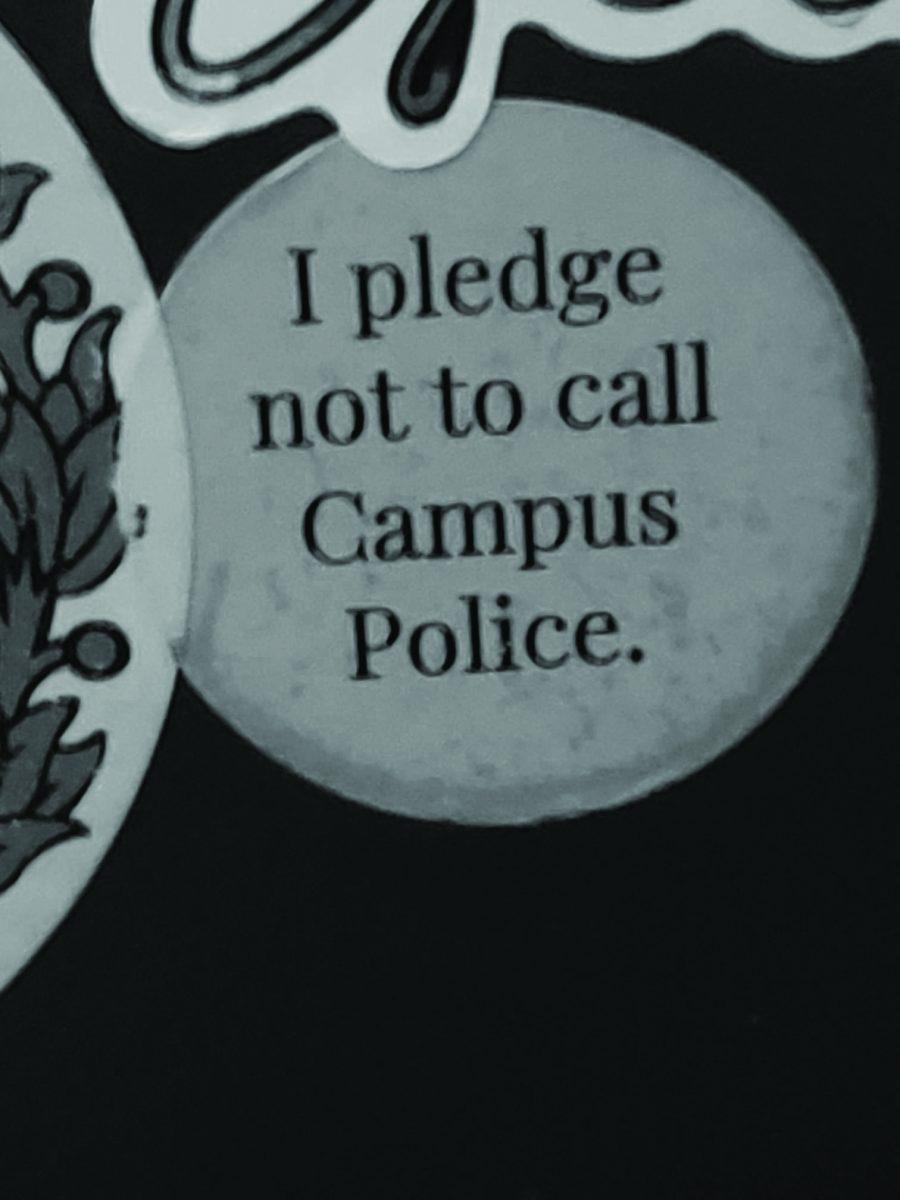

The campaign aimed at not calling campus police included a campus-wide poster campaign and stickers that students could put on their laptops, as well as a petition students could sign pledging not to call campus police. The posters suggest alternative solutions to calling campus police in different situations, usually suggesting that students talk to a member of residential life staff or try to settle disputes themselves.

One of the issues with calling campus police over situations like noise and marijuana use, according to the organization, is that Wellesley’s campus police are armed, making it possible for situations to unnecessarily escalate. Another issue is that overzealous calling can target students who were doing nothing wrong, as was the case for a Black student at Smith College who had campus police called on her for merely sitting in a common area in 2018. . Members of WAMI felt that the campaign has mostly gone well, with some minor issues.

“I feel like it was well-received with some people, [but] with others, it kind of felt unnecessary,” said Jordan. “I think that a lot of people who had themselves experienced having campus police called on them or a friend felt that it was important.”

Other students critiqued the slogan “don’t call campus police,” arguing that it might be confusing because it should not be applied to students who, say, call campus police to help with a friend who is blackout drunk. Jordan welcomed these criticisms and said that even for students who ultimately stuck to feeling critical and never signed the petition, it was important that they got to have conversations with WAMI.

Kelechi Alfred-Igbokwe ’19 added that several campus police officers were in support of the campaign as well, feeling that their time was too valuable to deal with unnecessary calls.

WAMI puts considerable effort into ensuring their campaign methods are as effective as possible. According to Ocheltree, for their last campaign they began by establishing a goal–in this case, the goal was that students not call campus police–and then took steps to research what methods would be ideal. They learned that poster campaigns had been effective in the past, which was one of the reasons they settled on a poster campaign.

The process will likely look different for the campaign aimed at asking the school to divest from private prisons.

“It’s going to be a lot bigger,” said Ocheltree. “We have to do a lot of research about where the college puts the money in the first place, which is not very transparent. We have to figure out how to get all of that, and get information, and try to work with the college to begin with.”

She added, “Going to the administration is always a good step, but in my experience the administration has not always responded positively to student requests.”

“A lot of [trying to get information] involves trying to pester people, because you don’t know exactly where to go for it,” explained Jordan. “It’s kind of hounding people and being like, ‘Hey, it’s us again!’”

As part of this process, WAMI plans to work with at least one other local college whose students are also planning on asking their administration to divest from private prisons.

The work WAMI does is important for a huge number of reasons. One major reason is that America’s current prison system, which incarcerates an especially high number of prisoners, often leaves prisoners vulnerable to abuse and mistreatment, and does not reduce recidivism.

“I think it’s very important because there are so many abuses that go on, and I think that the current system not only allows them, but encourages them,” said Jordan. “There is oversight, but it’s not actually effective, and it doesn’t prevent any of these abuses from happening. Our current system relies on human rights abuses to sustain itself.”

This is especially true for private prisons, who profit from having higher numbers of prisoners, a huge reason WAMI wants to ask Wellesley to divest from private prisons.

Students who are interested in helping incarcerated people can support WAMI’s campaigns and attending events like seasonal card-making for prisoners.

“We have a lot of privilege, and it’s important to use that privilege for good in this space,” said Jordan.