MIT students, faculty and researchers gathered at the Stratton Student Center on Sept. 13 to protest the University’s financial involvement with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. An incriminating investigation by New Yorker reporter Ronan Farrow brought light to the controversy surrounding the MIT Media Lab’s funding, which was revealed to have deep ties to Epstein. The report detailed how much more money was accepted from Epstein than the Lab had previously let on and how aware the administration was of Epstein’s deplorable past. The former director of the Media Lab, Joi Ito, resigned a week prior to the protest due to an independent investigation of the donations issued by MIT President L. Rafael Reif. The protest, organized by student group MIT Students Against War, came a day after a statement issued by Reif, declaring that although he “does not recall” it, he had thanked Epstein for his donation to the school. Reif admitted in late August that the University had accepted $800,000 — a figure much larger than what had been previously disclosed — from Epstein over the course of two years.

We should not need inflammation from political polarization, exposés ignited by the sudden re-emergence of a name in the news or the supposed threat of right-wing ideology on a historically liberal campus to prompt us to ask the all-important question: where is the money coming from?

Epstein was a prominent figure in hedge funds and had far-reaching connections to leading figures in politics and business. He also ran what many termed a “cult-like” network of underage girls who he repeatedly sexually abused and took advantage of, offering them hundreds of dollars in exchange for lurid and illegal acts. He was arrested in 2008 for these crimes but escaped relatively unscathed on a 13-month sentence in a county jail, having cut a deal for a federal non-prosecution agreement that acquitted him of a life sentence if he plea guilty to two counts of prostitution. Furthermore, his co-conspirators were never named or charged, and the deal was concealed from his victims until after it was approved by the judge, effectively silencing any possible sources of dissent. The US attorney in Miami at the time, Alexander Acosta, played a major role in reducing Epstein’s sentence and later went on to become the US Secretary of Labor in Trump’s cabinet — only to resign in the face of backlash for his handling of the Epstein case. Hiding the deal from Epstein’s victims was later ruled illegal by federal prosecutors. Epstein’s case was reopened and he was sent back to jail in 2018, where he died of apparent jailhouse suicide.

In an interview with Science magazine, Epstein detailed his interest in funding university research, citing the “Trump administration cutting back on pure research” as the motivation behind his donations. He acknowledged that some of his recipients may not have been comfortable associating themselves with him, which was why he made his donations in private: “If you want to tell people you got it from me, fine. If you prefer not to, for your own personal reasons, that’s OK, too.”

The uproar around accepting “dark money” has prompted other universities to investigate their own funding resources — Harvard University President Lawrence S. Bacow launched an ongoing review of the donations made to Harvard in the wake of MIT’s Epstein scandal. Epstein made several hefty donations to Harvard as well, the largest of which was a $6.5 million gift to the Program for Evolutionary Dynamics. Bacow announced that the University will be donating an unspent balance of $186k — discovered to be donated by Epstein to the Faculty of Arts & Sciences)to charitable organizations fighting human trafficking and sexual abuse. Reif similarly announced that MIT would donate the same amount of money they had received from Epstein — $800,000 — to charities supporting victims of sexual abuse.

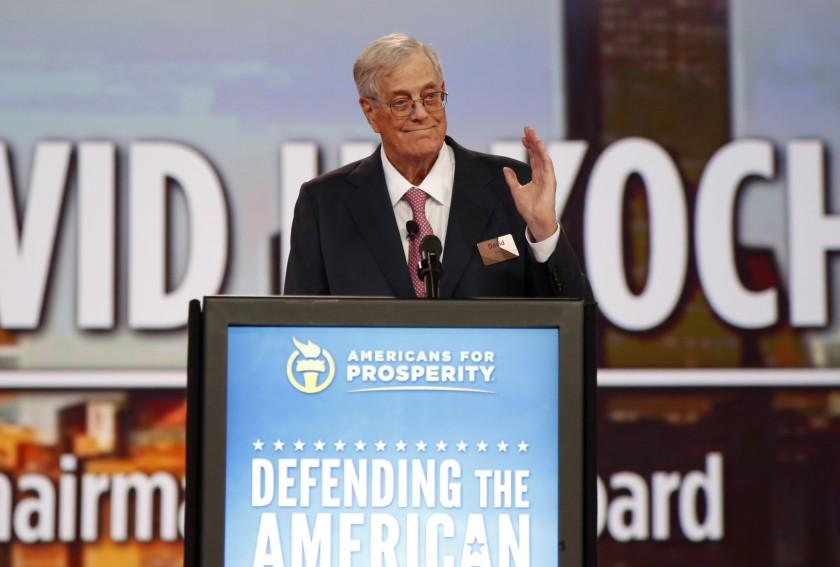

Wellesley is not immune to the serpentine nature of dark money. The college has received donations from the Charles Koch Foundation, the founder of which has received harsh criticism and backlash for the seemingly unscrupulous methods he and his late brother, David Koch, employed to amass their empire. A scathing 2014 report by the Rolling Stone exposed several of the darker facets of Koch Industries, including record-breaking levels of pollution and environmental degradation as well as civil lawsuits, congressional investigations and even felony convictions. Koch Industries reportedly pollutes the nation’s waterways more than General Electric and International Paper combined, and the Koch Pipeline Company was handed down the largest wrongful-death of its type at the time when a faulty pipeline killed two teenagers.

The Koch Brothers have also long been accused of using their influence and wealth to consciously shape American politics and thought to match their particular brand of right-wing conservatism, whether it be through directly funding nonprofit campaigns that push specific ideologies or by financing the creation of think tanks to evaluate the future of American policies. And while the outrage that followed the Koch brothers funding a project on campus eventually simmered as a result of the active restructuring of the project on President Paula Johnson’s part and a temporary overhaul of the program, the issue still stands. The situation may seem diffused now: the projects were reviewed and restructured and the donations are under investigation. However, these efforts have undertaken in the isolated incidents where dark money has been exposed.

Dark money is the cornerstone of the entire university research sector. Schools often rely on money from private donors, to the extent that they are willing to turn a blind eye to any questionable motives or sources. These controversial leading figures in financial support, who are too often embroiled in controversy and scandals, use their ties to established, prestigious institutions to direct attention towards their supposedly “philanthropic” intentions and away from the ways in which they abuse their opulence.

We need to stand in solidarity with schools like MIT and Harvard in their attempts to dismantle the all-too prolific integration of dark money into universities and colleges. Students and administration must be more transparent about the sources behind the research centers and projects on our campuses.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that “those who openly accepted money have stepped down or are currently under heavy scrutiny.” We have removed this line as it can be misinterpreted as a reference to Professor Thomas Cushman, who voluntarily decided to transition the leadership of the Freedom Project to Professor Kathryn Lynch.