On the surface, N. E. B. Ostermann, lived a typical life. Ostermann graduated from Wellesley College as a German Literature major in 1936 and obtained post-bachelor degrees and experience at Northwestern, University of Munich and the Chicago Technical School. Later, Ostermann got married to a man and settled in New Jersey. Then in 1952, Ostermann was involved in a tragic accident that caused him to re-evaluate everything.

Following the accident, Ostermann started calling himself Nicolas, after the Czar of Russia, who he claimed was an uncle. Nicolas divorced his husband and settled in the Chicago area, working as a set designer for theatrical productions. He also worked in interior design, mechanical and architectural drafting, and town planning; some of his clients included Macy’s and Gimbels.

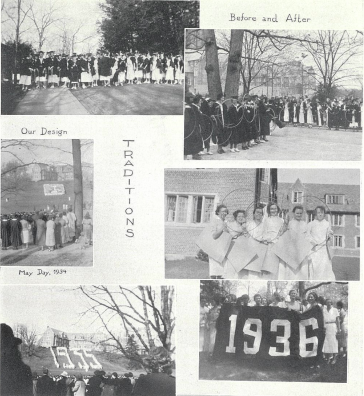

At Wellesley, Ostermann was a German Major and involved on the Hockey team. He participated in Float Night as a substitute punter and was a member of Eliot Dorm, which was a dorm located around the corner from Scoop. He had a sister who was three years younger than him and also attended Wellesley.

Nicolas began transitioning in the 1950s, following the car accident mentioned. He was placed in a sanatorium for “mental unwellness,” a diagnosis potentially related to his gender identity. While in the sanatorium, his mother wrote a letter on his behalf to the 1936 Class Council, informing them that Nicolas was disappointed and would not attend reunion.

In Ostermann’s own words he had a “near fatal injury in 1952, I discovered that I was not a woman at all. I have spent the years since that time piecing together what is certainly one of the most unusual histories in the annals of the human race.” Later in 1981, Ostermann called the experience an “unexpected, though not unhoped for, turn” and was “truly a blessing.” Describing his own gender identity, Nicolas said that he had to clarify often in communications with alums and administration that he “did not have a sex change. [He] had a sex revelation … I did turn out to be a male in disguise. In a different letter, he said, “As the world is full of imposters, it is important to know that Edith and Nicolas are one and the same person”

Nicolas’s own journey to his gender identity can best be described in his own words. In 1964, Ostermann wrote a letter to a publication saying, “As each Christmas season has come and gone, I have despaired of making it to the next, not so much because I have not learned how to survive against the odds, but because my mind cannot blot out the memory and the promise of its rightful environment … I am settled, pending improvements, in an apartment in a part of Chicago relatively unfamiliar to me … I would give anything to be able to chat with you privately and tell you who I really am … I desperately need to know that is still a real world and that its doors are not barred against me. I have no such knowledge now … I’d like to thank you, severally and all for what I know you weren’t aware of providing, you gave me nourishment in a lifetime of starvation and I hope that somewhere on earth and in heaven you will be adequately rewarded for it.”

In 1996, Nicolas’s sister wrote to the Wellesley magazine about his death saying that “she was quite a memorable person.”

The life of N.E.B Ostermann challenges the traditional history of Wellesley and provides a unique story through which to reflect on our current environment for our non-binary and transgender siblings. Nicholas’s story is one that has been erased and pushed out of the narrative. Wellesley has always been an institution for those who faced misogyny and homophobia, and this is not a recent development. The administration and older alums believe that Wellesley has always been a place for women, but Nicolas’s story is one of many that have been recently uncovered. Through celebrating and recognizing the life of Nicolas Ostermann, we hope to celebrate all the unrecognized non-binary and transgender students and graduates and connect to those who came before us.

The rediscovery of N.E.B. Ostermann’s life could not be done without the efforts made by the Wellesley Archives Staff, Rebecca Goldman, Sara Goldman, Rebecca Ludovissy, and Natalia Gutiérrez-Jones.