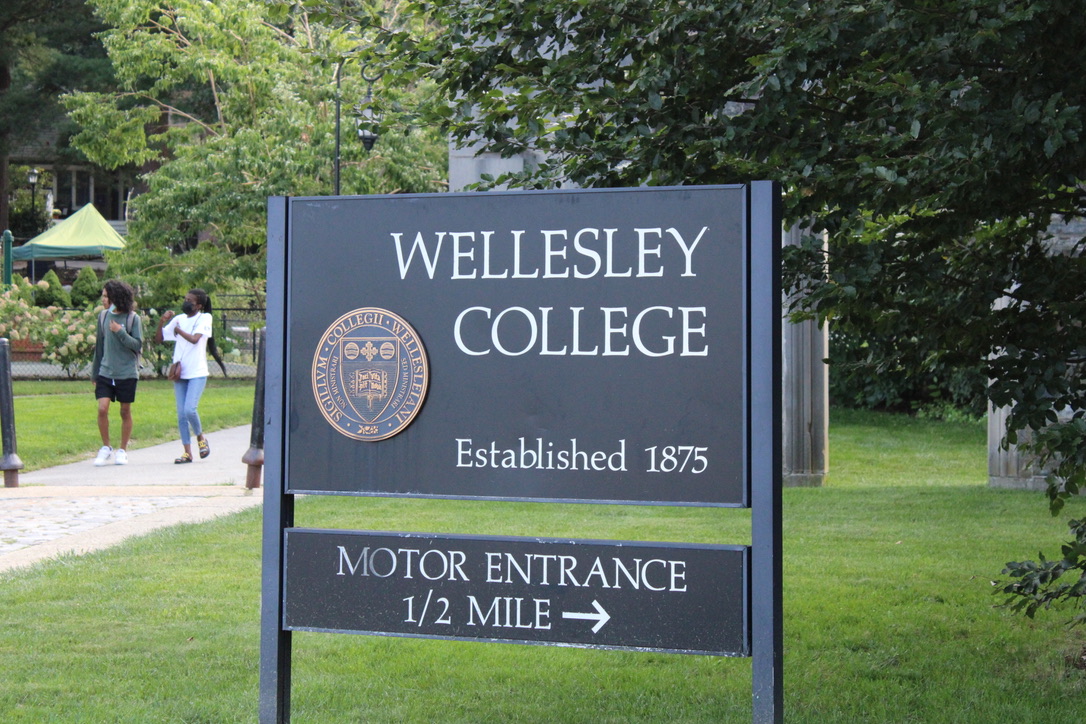

This past August Wellesley’s most recent rounds of financial forms were released, highlighting the various expenditures of the college including administrative salaries and total tuition revenue. The tax return, which was filed as a Form 990, is an Internal Revenue Service requirement for all non-profit organizations as a way to ensure transparency and that funds are being allocated appropriately. The Form 990 shows what the college is spending on what, how much upper administration is being paid, and how much students are paying.

According to Piper Orton, VP of Finances at Wellesley, the way money moves around this school has changed in the past year. “I think the first change is the recognition of the need to fund more deferred maintenance and campus renewal from current operations,” she said. Additionally, in a presentation to Senate on Oct. 8, Orton mentioned that current efforts to reduce discretionary spending are due to the school’s dependence on deficit spending following the 2008 financial crash.

“The second change was the offer of the voluntary retirement program (VRP) in FY2018. The decision regarding the VRP was guided by the need to recast our budget model in order to support institutional priorities and invest in a sustainable manner, both in our academic program and in our campus facilities.” The VRP was a pay-out program the college created in order to encourage professors to leave and to decrease the size of the faculty.

Some of the most striking of the data available on the Form 990 was that describing tuition and cost of living increases over the past decade. Between the submission date of the 2011 forms and that of the 2018 forms, which are measured by fiscal year, the total revenue the college receives from tuition, fees, room and board increased from $123,407,761 to $156,443,601, an increase of 26.7%. The student population, meanwhile, barely increased at all–with an increase of only 30 students, or 1% of the total number of students here. However, the increase in total revenue coincided with a 40.80% increase in the comprehensive cost to attend the school, according to data obtained by the Office of Institutional Research Studies.

Although the amount of tuition revenue the college gets each year has increased by millions of dollars, the amount given in financial aid per student on aid has gone up–by roughly 40%—too. The number of students on aid has remained roughly constant between those years, at around 1,250 out of Wellesley’s ~2,500 students, or around 50%. According to Orten, due to the high rate of students on financial aid the net revenue from tuition and fees that Wellesley received from students during the 2019 year was only $41,859, while the amount spent per student was $97,796.

Wellesley’s tuition increase over the past seven years was higher than that at the average private four-year institution, according to data from the College Board. The average institution increased tuition 23% over that period (adjusting for inflation) while Wellesley’s tuition, room, board, and fees grew even more rapidly.

According to Karensa DiFonzo, head of the Office of Student Financial Services (SFS), these tuition increases have coincided with a higher number of students coming to SFS to apply for aid than ever before. “Tuition increases don’t really impact the way that Student Financial Services runs, but it has impacted our volume,” DiFonzo wrote in an email to the News. “We have more students than ever applying for financial aid and many more families are seeking advice on loan options and payment plans.” She noted that most of that aid goes to domestic rather than international students, as only about “one-fourth to one-third” of the international student population is on financial aid, while close to 60% of the total student population is. These numbers are also evident in terms of the school’s listed expenses: about 60 million is spent on domestic student aid, while about $5,741,711 is spent on international student aid. That equates to about ten thousand dollars of aid per international student at this college per year, and twenty seven thousand dollars of aid distributed per domestic student at this college per year.

These forms also listed the cumulative and individual highest salaries at the College. $5,076,169 went to the salaries and benefits of Officers, Directors, Trustees, Key Employees, and Highest Compensated Employees– which included two professors, Frank Bidart of the English department and Richard French of the Astronomy department, who have salaries in the 200,000s per year which are high enough to be reported on the 990s. That figure goes up to 5,483,307 when you factor in retirement and other non-taxable benefits. President Paula Johnson and Debra Kuenstner, President and Chief Investment Officer, had the highest individual compensation-$643,524 per year for Johnson, and $619,235 for Kuenstner. According to Orten, staff expenditures, including faculty benefits, amount to about 64% of total expenditure by the school.

All of this information exists in the context of the school’s total revenue for the year, which comes primarily from investment interest. In Fiscal Year 2018, per the 990s, that revenue was 269,268,208 dollars. The total functional expenses of the college, however, were significantly higher than their revenue: $313,573,138. This trend of higher expenditures than revenue and debt spending has been ongoing except for major budget cuts following the 2009 financial crash and an exceptional gift in 2017. Consequently, the school has relied heavily on debt spending, something which Orton described during a presentation to Senate as “not sustainable.” Stone-Davis Senator Alexandra Brooks ’23 voiced her concern following the presentation over the “general trend of spending more than the income of the school and no long term solution on how to break-even.”

However, this doesn’t mean the college is headed towards financial disaster, as their total assets are still worth over two billion dollars. Most of that resides in the college’s endowment, though, which means that much of it is not necessarily accessible for things such as the building repairs student activists have been demanding this year. 43% of it comes from restricted giving, so it can only be used for what the donor specified it be used for. Orton explained this as a function of alumni giving choices. “The endowment represents gifts from generations of alumnae and others who have designated that their gift must be held by the College in perpetuity, with only earnings on the gift to be used, never the principle.”

The four construction companies who as of fiscal year 2018 had contracts with Wellesley were being paid between one and five million dollars apiece as part of the school’s five year plan to renovate facilities. Orton was able to explain more about how the construction is being funded, and said that this is working primarily through tax-exempt bonds issued by the college. “The L-wing renovation and the replacement of Sage will address $100 million of deferred maintenance that otherwise would need to be addressed,” she said, though she did not specify why that maintenance was deferred. “We issued tax-exempt bonds of $96 million in March of 2018 to help fund construction expenses, and are incurring additional interest expense and use of cash for principal payments related to the debt. Fundraising efforts are underway to address the new building costs.”

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the amount of financial aid money allocated to international students per year, and incorrectly asserted that Wellesley has been dependent on debt spending rather than deficit spending following the 2008 financial crash. In addition, it stated that 64% of the school’s expenditure goes to faculty salaries, when in fact that percentage refers to all staff, faculty, and administrator compensation. The Wellesley News deeply regrets these errors.