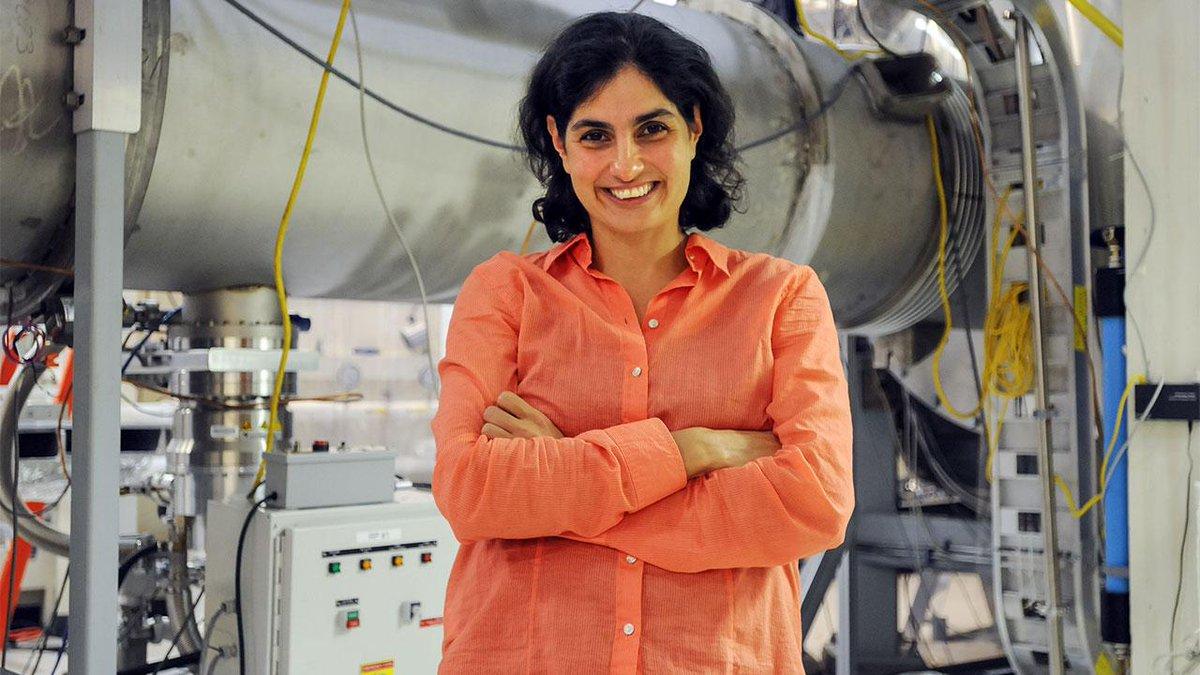

Questions regarding the universe have fueled conflict, sparked controversy, and inspired creativity for millennia. It is a seemingly impossible subject to master – but astrophysicist Nergis Mavalvala ‘90 has dedicated her entire career to making that possible. Mavalvala, a renowned researcher in the areas of gravitational waves and quantum measurement science, was appointed in August as the newest dean of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) School of Science, making her the first woman in the school’s history to serve in this position.

Mavalvala is acutely cognizant of her unique position as a powerful woman in STEM, and her vision for the future of the field is a more inclusive one – to provide a level playing field for those who want to break the omnipresent glass ceiling and pursue a successful and enriching career such as her own.

“I am a member of many minority groups – being a woman, being a person of color, being queer – all of those things are serious impediments to progressing in a STEM career for members of those groups,” Mavalvala said. “I know that my story is very unusual, and the more usual story is that membership to these groups holds people back, or it certainly gives them many negative experiences.”

Mavalvala was born in Lahore, Pakistan and later raised in Karachi. She arrived at Wellesley in 1986 as an international student, and attributes her greatest support system to the community at Slater International Center. In addition to her intensive research in the physics department, she also involved herself in the intramural squash team and spent a year abroad in Germany, almost declaring a minor in German during her time at Wellesley.

“Being a woman in a male-dominated field is a very interesting experience. While I was at Wellesley, I never fully appreciated that women were a rarity of sorts in STEM,” Mavalvala said. “Then, when I was doing my junior year abroad, and I went to my first physics class in Germany, I walked into a huge lecture hall with over a hundred students and I saw that there were only two other women in that room.”

Although she was drawn to the sciences from a young age, Mavalvala found that the liberal arts curriculum at Wellesley would better serve her broad interests in the humanities and social sciences than a larger research institution. This was largely influenced by the curriculum she had experienced in Pakistan, wherein students were confined to certain areas of study early on in their education and it was difficult to take courses in subjects outside of their respective fields.

“I don’t think I fully knew at the time how truly perfect Wellesley would be for me as a student,” Mavalvala said. “Early on when I was making my college choice, I decided I wanted to go to a liberal arts college. [In Pakistan] I was already on the science and math track. I wanted to broaden my education.”

While studying in the physics department at Wellesley, Mavalvala was introduced to her first research opportunity with professor Robbie Berg, who still teaches at Wellesley, whom she cites as one of the greatest influences of her career. Mavalava also drew inspiration from her lab work with current Wellesley professor Glenn Stark, another mentor who helped push the trajectory of her career toward physics research on a larger scale.

“My research experience at Wellesley was unforgettable. There were so many others who either were influential because I learned a lot from them in terms of research or technology, or who simply helped me out emotionally,” Mavalvala said. “Those are the people who have sort of carried me through my career and have walked the journey with me.”

After her departure from Wellesley with a degree in physics and astronomy, Mavalvala went on to pursue a PhD in physics at MIT, graduating in 1997. As a graduate student, she worked under MIT professor emeritus Rainer Weiss, who served as her physics adviser and was one of the founders of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), which was a system of large observatories with the aim of detecting gravitational waves by laser interferometry.

“The precision we needed to achieve in the instrumentation was something that had not only never been done before, but was seen as unattainable. Even when I first heard about it myself, as a graduate student, I thought it was crazy – how could we be so audacious to think we could do this?” Mavalvala said. “We had to invent everything – all the technology we needed was to be built from scratch. Early on, I knew that if we could do it, it would change the way we perceive the universe. So the payoff was going to be huge.”

Mavalvala has since dedicated nearly 25 years to LIGO. In 2016, she found success when her team made the first direct detection of ripples through space in the form of gravitational waves. The following year, as a result of her historic breakthrough, Mavalvala was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, a nonprofit comprised of scientists that is meant to advise the government in science, engineering, and medicine.

“Another thing that marked my career in gravitational waves in the long haul, from the time we started to when we made our first discovery, was that I really loved the people I was working with,” Mavalvala said. “It could have turned out differently, we could have been here today having not discovered anything. It turned out well, and not only did we make the first discovery, but we have started to make routine observations of objects in the sky like black holes and neutron stars. We’re continuing to improve the instruments and look for more unusual objects. So it turned out well, even though there was risk.”

Currently, as MIT’s School of Science dean, Mavalvala plans to combine her experience as a veteran researcher in astrophysics and as a member of several historically marginalized communities to introduce a new culture of equal opportunity in STEM.

“I also do want MIT, the School of Science, and all the departments within it, to really confront very difficult issues, that have to do with a culture that is not inclusive, to confront who has access to this level of science, and how can we broaden that access, what are the social barriers, how can we fix those,” Mavalvala said.