When Jane* received a phone call from contact tracers on the afternoon of Oct. 7, she had expected anything but the news she was given. She was informed she had potentially been exposed to a student who had tested positive for COVID-19 and that they would call her back in an hour to confirm, during which she was asked to remain in her room.

She later received a second phone call that confirmed she had been exposed to the virus and was asked to move immediately to the College Club to begin quarantine. Shortly after, Jane received an email from Director of Residential Life and Housing Helen Wang that verified her status as a close contact. She and her blockmates, who were also exposed to the same individual, were then sent another email with a basic packing list and further instructions, such as who to contact when they arrived at the Club.

Jane described the overall information provided as “vague.” The only guidance that was given was outlined in a pamphlet from the College, with the rest expected for her to figure out herself. Beyond the meal, trash, and departure protocols, Jane was on her own for the next fifteen days.

“They showed [us our] rooms and that was about it,” Jane said, noting that they were not given keys.

Two of the greatest challenges she faced while in her two weeks of quarantine was isolation and boredom. From her room, Jane could see students outside enjoying Fall Break and events, but could do little herself other than sit at her desk and lay on her bed. After two weeks, Jane found seemingly small actions to be increasingly challenging, including the move back to her dorm room.

“No one expects it to happen to them,” Jane said. “[It was] a lot of feeling like you needed to move, but couldn’t.”

In an email over the summer, President Johnson described Wellesley’s plan for quarantine protocols. At the time, a health and safety team was partnering with the Commonwealth, the Wellesley Department of Public Health and the Newton-Wellesley Hospital to establish “quarantine and isolation protocols that would follow best practices and the guidance being developed by the Commonwealth.” Later the College elaborated and said they would reserve quarantine and isolation spaces in dedicated campus buildings.

Despite this planning, more specific quarantine protocols were not clear to the student body when Fall Intent forms were submitted. Jane was originally told she only needed two negative tests and was given two different quarantine release dates that differed by three days. Despite many health officials and the college stating that quarantine would last fourteen days, Jane and Olivia* — another quarantined student and Jane’s blockmate — stayed for fifteen days.

In total, the quarantine process involved contact tracers, dining workers, club staff, Health Services, the Newton Wellesley Hospital, and College administration. However, the multitude of channels made it difficult to follow exactly what was happening. While Olivia was impressed with the work and effort the contact tracers put in, she also found herself frustrated by their miscommunication.

“[There was] a lot of conflicting information when [we] first got there,” Olivia said. “[The] contact tracers were giving us different information from the nurses from Health Services.”

Regimented testing started the morning after the students arrived with testers coming directly to their rooms. Over the two week and one day period, they were tested a total of four times. The testing schedule was not consistent or scheduled ahead of time; on one day, Jane was not given a test and then assigned a surprise test the next morning. Jane took her fourth COVID-19 test on the Monday before her Thursday departure. Although she had tested negative, Jane could not return back to her dorm because she still had to finish the mandatory two week quarantine.

In a statement to The Wellesley News regarding the lack of clarity, Karen Petrulakis, General Counsel and leader of the Health and Safety Committee, directed students to the Keeping Wellesley Healthy website for more detailed information regarding the quarantine and isolation protocol.

“Thankfully, we have only had two positive cases since the pandemic began that required individuals to be quarantined, and we have been lucky to not have needed to have a lot of practice with these protocols,” Petrulakis said, drawing attention to the quarantine student guide. “With each case, and each students’ experience and feedback about quarantine and isolation, we identify how we can improve and what additional resources would be helpful to students.”

In the last weekend of her quarantine, according to Jane, she and her fellow students were left without water for almost a day. Jane called and emailed Health Services and Res Life asking for water, but it did not arrive until dinner that day; instead, she relied on the single bottle of water she saved from dinner the night before.

“[They] can’t just leave people who are relying on them for basic necessities alone for two days,” Jane said. “[They need to] have someone we can call who will pick up.”

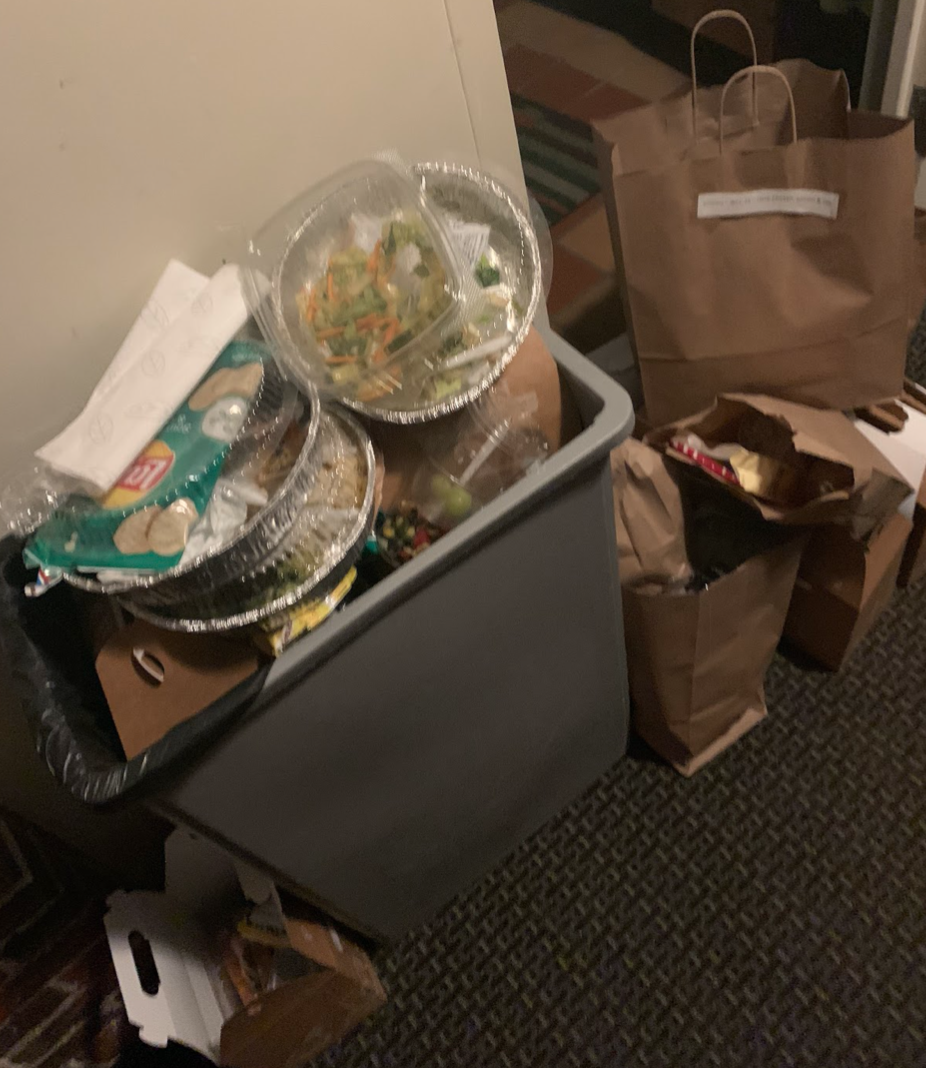

The only consistent part of quarantine was the meals. Breakfast was brought around 9 am, lunch at 1 pm and dinner at 6 pm. On weekends, brunch was served at 11 am and dinner at 6 pm. Food consisted of sandwiches, salads, oatmeal, fruit and occasionally a dessert.

However, both Jane and Olivia described significant portion and quality issues at the beginning of quarantine.

“Some days the portions were very little, and some days it was a lot and the variety of the menu was not enough,” Olivia said.

After three days of asking for larger portions, Jane’s portions finally increased, but the size still varied. Jane also had issues with her dietary restrictions being recognized, learning the hard way that unless she listed the exact foods she could not eat, she would often find an unwelcome surprise in her meals.

The students were allowed to leave their rooms to leave their trash from meals in the hallway. However, because these were not always collected in a timely manner, it attracted fruit flies and gnats in the hallways. The staff often set the food for the students near the trash, which resulted in a particularly memorable moment when Jane found gnats “crawling in her sandwich.”

[separator type=”thin”]

In order to be released from quarantine, the students had to meet virtually with a doctor who asked about their symptoms. Afterwards, administrators from the Office of Residential Life met virtually with the students in quarantine to detail dorm arrival. A little more than two weeks after the start of their quarantine, Jane and Olivia were released.

“Everyone knew we had been in quarantine, especially in the residential hall,” Olivia said, because the Community Director had emailed the entire residential hall about what time the quarantined students were expected back. While their privacy was somewhat respected, the triumphant return left much to be desired.

Jane believed Wellesley was not considerate in how they handled the situation.

When we decided to come for fall semester, I don’t think we expected it to be like this.

“This experience left me really disappointed in Wellesley,” Jane said. “[It was] so disorganized and not prepared for anything. When we decided to come for fall semester, I don’t think we expected it to be like this.”

More than anything, Jane and Olivia do not want to quarantine again.

[separator type=”thin”]

*Names have been changed to protect student privacy.