Content Warning: Abortion and Prison Abuse

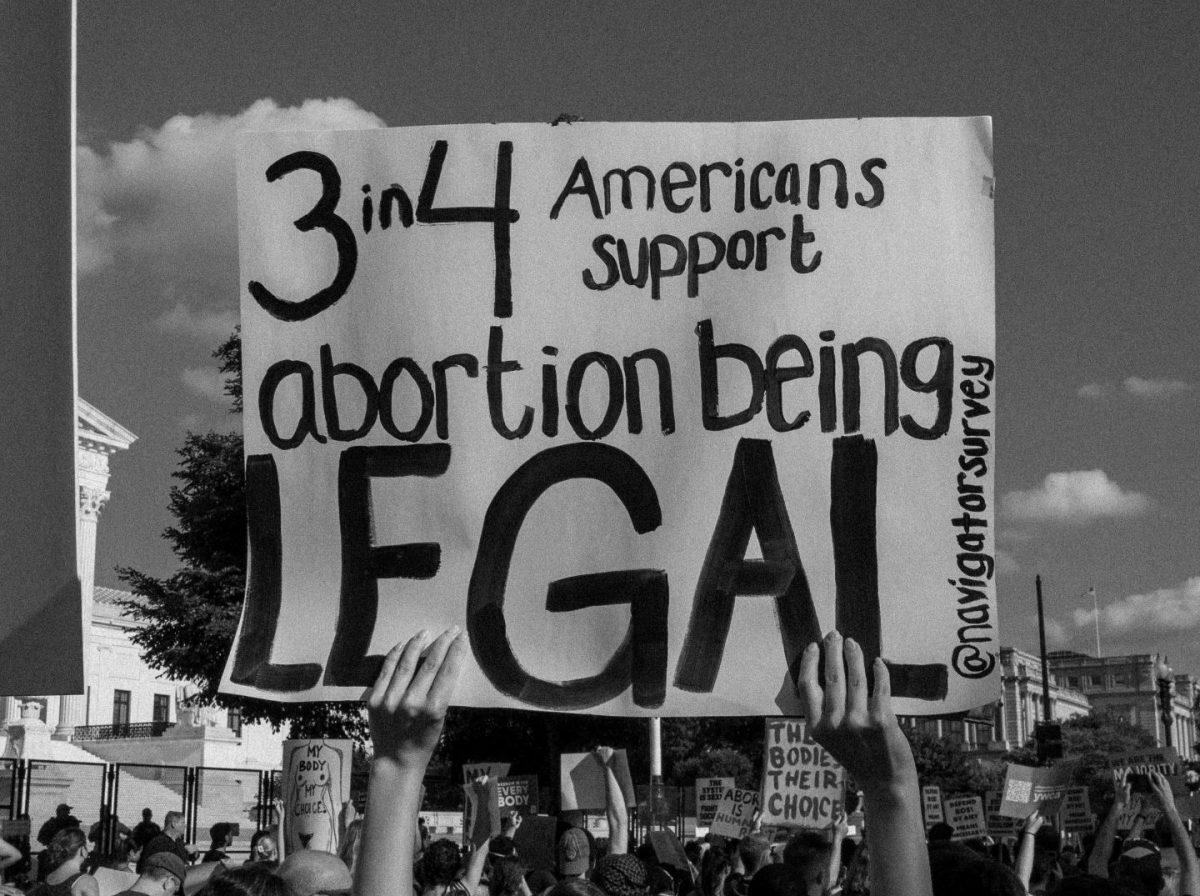

On June 24, 2022, the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, taking away the federal right to abortion. Reproductive rights activists took action immediately, continuing their work from years prior to make abortion more accessible. On Nov. 30, Wellesley Against Mass Incarceration (WAMI) teamed up with Wellesley for Reproductive Justice (WRJ) to discuss the effects of criminalizing abortion, both on a national and local scale.

The meeting began with a brief overview of the history of abortion in the United States. It was emphasized that before 1840, abortion was neither up for debate nor heavily stigmatized. In 1840, men in the medical field began to work to outlaw abortion in order to increase their own power in the medical system. This framing of abortion stuck until 1973 when the Supreme Court passed Roe v. Wade. It is important to note, however, that Roe v. Wade only allowed for a legal right to abortion — it did not ensure equal access to reproductive health care. Roe v. Wade served as a legal basis until this past June with the passing of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

The overturning of Roe v. Wade and the ramifications of inequitable access to reproductive health care were examined during this joint session on Wednesday, exploring the issue through many different lenses including health, economic and criminal justice impacts. Although these may be considered different categories, the overlap between each can be seen through the issue of reproductive health care.

The lack of access to abortion has many health effects, as outlawing abortion does not mean stopping abortions overall —only safe abortions. Similarly, state bans on abortion work against many doctors’ wishes, putting them in a dangerous place of deciding between potentially losing a pregnant person’s life and being reprimanded by the law. It was highlighted in the meeting, however, that prosecutors should be discussed more in the conversation around reproductive justice, as they choose which cases they take up and do not have to take abortion cases. This is just one example of the widespread nature of reproductive justice not only affecting those with the ability to become pregnant and those in the medical field, but those in all fields.

From an economic perspective, abortions are expensive, especially with increased travel costs to states where abortions are still legal. This increases strain on lower income individuals, as they do not necessarily have the time or the resources to travel to receive an abortion. There are also implications for affordable housing and welfare, as individuals’ homes are given different treatment than those of families, causing the ability to get an abortion to potentially dictate what kind of housing a person would receive.

The meeting also included discussion of prison justice in relation to reproductive health care. An increase in abortion bans has led to increased incarceration, which shows how prison justice is a relevant topic of discussion in reproductive health care. WAMI and WRJ used a local example to illustrate the need for reproductive health care in the prison system with the institution of Massachusetts Correctional Institution — Framingham (MCI-Framingham), showing how even in a blue state with a legal right to abortion, there is still work to be done. In interviews conducted as part of an investigative report last year, people in MCI-Framingham discussed how they have limited access to sanitary products such as pads and tampons — let alone shampoo and deodorant. This leads to families having to use money they may not be able to spare to send these supplies. Similarly, Massachusetts law prohibits people being shackled while in labor, but the report states that this is not followed at MCI-Framingham.

These are just a few of the areas of advocacy in the reproductive justice movement brought forward by WAMI and WRJ. They concluded the meeting with a “utopia” thought exercise, asking members to think of ways that the Wellesley, Massachusetts and United States communities could provide better access to reproductive health care. Makayla Almonte ’24, president of WAMI, shared why it is important to have conversations like these.

“I don’t think people conceptualize just how much the criminalization of abortion overly impact[s] women of color and low income communities. It’s important to know that because of this decision there are thousands of people, millions of people, not even just women [and] people with uteruses. Everyone is going to be affected by this and it’s going to last for generations.”