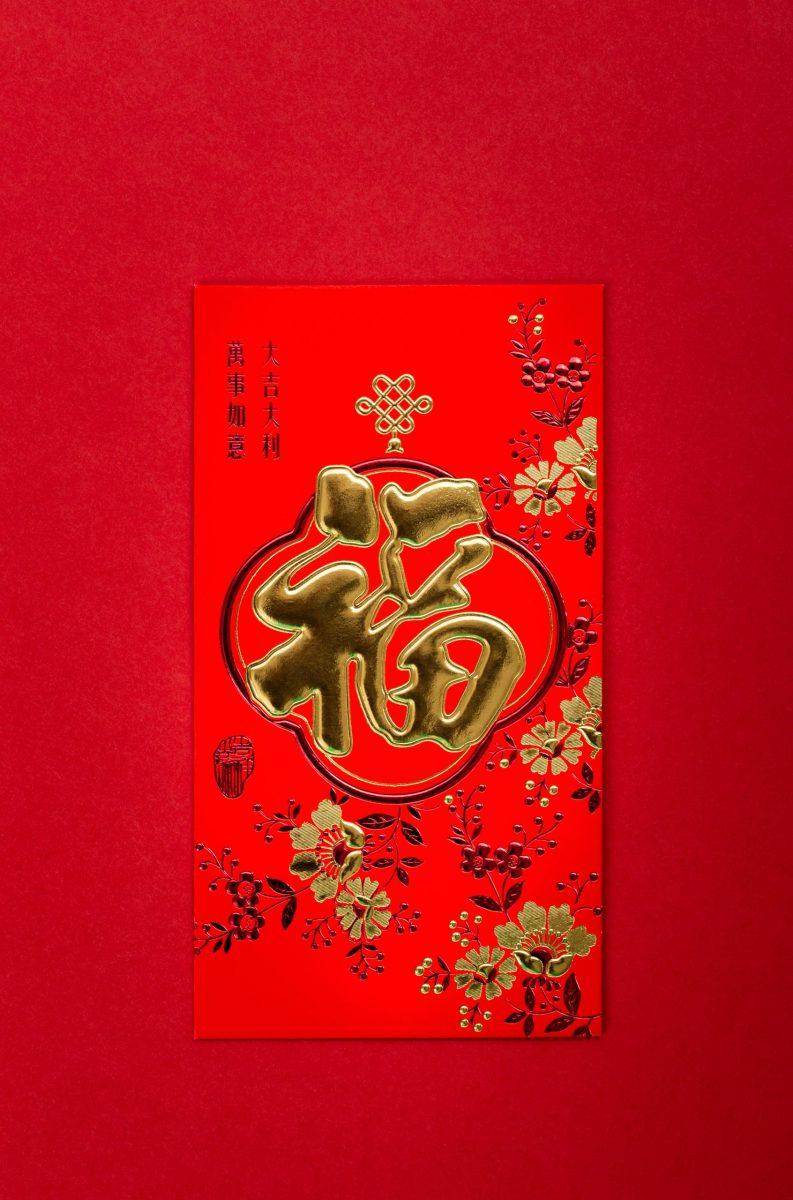

The coming of the Lunar New Year brings many things: good luck, red envelope money, house cleaning and forgotten traditions. Recently, Holly Hoang (TikTok: @hollynhoang), a small Chinese Vietnamese American influencer, went viral for wearing a “traditional yet modern” version of a qipao (Cantonese: kei-poe).

A qipao is a classic Chinese long dress, adorned with elegant and intricate silk designs. From watching Maggie Cheung in the early 2000s Shanghai-nese romance movies to celebrating the coming of the Lunar New Year, the qipao can be worn for both formal and informal occasions.

Although Hoang’s main goal was to modernize the classic qipao, in reality, she sexualized a cultural garment. In contrast to the conventional long dress, Hoang wore a custom made two-piece qipao, consisting of a short sleeve bra top and a miniskirt.

Unfortunately, this instance of cultural ignorance is neither the first nor last of its kind. As a result of social media and the bandwagon effect, it has become a trend among young people to modernize cultural traditions, such as clothing, food and style. However, in this context, modernization means that the cultural component of the traditions has been omitted completely. One example of modernization is “fusion foods” which take away the authenticity and the familiar “taste of home” that international students and immigrants yearn for in an attempt to make food look new and improved. The recently popular “clean girl” aesthetic is an insult to Latinas and Black women, whose slicked back buns and gold hoop earrings have been stolen by white women and molded to fit Western beauty standards.

Some may say that these are simply forms of cultural exchanges from one country to another. Although there have been previous instances of a proper and polite cultural exchange, such as when people from mainland China applauded the Utah teen who wore a qipao to their prom in 2018, these aforementioned actions cross the line into cultural appropriation.

What exactly is cultural appropriation? In the past decade, the term “cultural appropriation” has permeated our everyday vernacular, frequently referencing something a celebrity has worn on the red carpet. Cultural appropriation is not as simple as Ariana Grande’s misspelled Japanese tattoo. Rather, it is the adaptation of cultural elements by a dominant culture without paying homage to its original culture. Whether it is having a Polynesian tribal tattoo or the Westernization of Black and Latinx fashions, it is the cherry-picking of certain “alluring” aspects of a culture that contributes to the inherently imperialistic nature of Western society.

American culture, especially, has turned into one of cultural imperialism, taking only the attractive cultural elements and leaving the rest behind without respecting its origins. In 2015, Nicki Minaj directly confronted Miley Cyrus — and indirectly confronted the entirety of Hollywood — regarding this cherry-picking, “You can’t want the good without the bad. If you want to enjoy our culture and lifestyle … then you should also want to know what affects us, what is bothering us, what we feel is unfair to us. You shouldn’t not want to know that.”

The qipao itself has had a long and vibrant history from the 1900s when Chinese women wore qipaos as a form of protest against traditional gender roles, to the ’60s when the clothing garment expanded its reach through becoming a global trend and the ’90s during the fashion industry’s time of experimentation and cultural appropriation of the qipao (and other cultural clothing pieces). Rather than respecting and recognizing the qipao’s impact on history, Hoang chose to forgo the symbolic significance of the dress and instead sexualized a piece of clothing rooted in feminism, diametrically opposing that it stands for.