On May 27, 2023, during the NCAA rowing championship, I rowed in the Wellesley varsity eight as it crossed the finish line, securing a national title and team championship. Crew has been a fundamental part of my Wellesley experience and it also played a significant role in my acceptance, as I was recruited to row and participate in Wellesley Athletics.

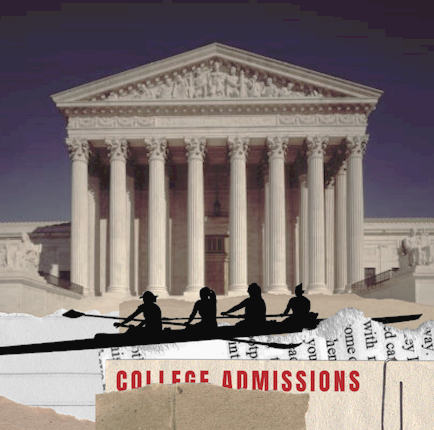

About one month later, on June 29, the Supreme Court of the United States struck down affirmative action programs, which were created to promote applicants who have been historically discriminated against and underrepresented, in response to lawsuits against Harvard and U.N.C. It claimed that considering race as a factor in admissions violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. This ruling was met with significant public outrage, for example, many activists brought attention to admissions policies that favor white upper-middle class applicants. Significant criticism was directed at legacy admissions, with some colleges opting to end legacy admissions altogether.

Athletic recruitment also came under fire. As it stands, athletic recruiting significantly favors white applicants, particularly at smaller elite institutions, including the Ivy League and top ranked liberal arts colleges. At many Ivy League colleges, student athletes generally represent around 15% percent of the student body. At elite liberal arts colleges such as Williams or Amherst college, student athletes frequently comprise 30-40% of the student population. At Bowdoin, over 820 of the school’s 1,900 students participate in varsity athletics.

Having a large number of student athletes isn’t inherently a problem, and many of these students walk on to varsity athletics programs after being admitted. The consideration of athletic performance in college admissions is conceptually no different than the consideration of any other extracurricular activity: it gives admissions officers a clear picture of the impact a prospective student might have on campus and a sense of how they will fit into the college community. Yet when schools actively recruit elite athletes to play at their institution, unlike nearly any other extracurricular activity, college admissions favors athletic achievement above all else.

Furthermore, athletic recruiting is racially biased. At these smaller institutions, upwards of 70% of the recruited athletes are often white. The Harvard Crimson reported that in Harvard’s class of 2025, 83% of recruited athletes were white. Additionally, college athletes generally come from more privileged economic backgrounds. This is largely due to access to financial resources that allow students from wealthier backgrounds to participate in sports from a younger age, and gain access to better equipment and coaching. Many niche sports have inherent physical and financial barriers that make it incredibly difficult for low-income students to participate.

Rowing is a perfect example of these exclusionary factors. While there are continued community efforts to make rowing more inclusive, the demographics of the sport reflect its traditionally racist and classist history, with people of color making up just 13% of rowers at all levels and 27% of collegiate rowers. As a sport, rowing poses several economic barriers related to the cost of equipment. Many clubs charge high school members 500-700 dollars per season, upwards of 1500 dollars a year. Beyond that, there are many physical barriers to rowing. Boathouses have to be on specific bodies of water which often require athletes to travel 30 minutes to an hour just to practice; this time is a luxury that many can’t afford. These physical and economic barriers are consistent across other sports such as skiing, sailing or golf, as well.

In addition to being financially and racially biased, recent research shows elite high school athletics can be damaging to the physical and mental health of young athletes, particularly girls. Young female athletes frequently experience higher rates of mental distress and body image issues. Moreover recent scholarship has focused on how athletic recruiting places a disproportionate amount of pressure on female athletes, requiring them to reach a performance peak when they are physiologically most likely to plateau. This is an experience that is all too familiar. My recruiting process was incredibly stressful: my self-esteem became tied to my athletic performance. My splits became a measurement of my own self-worth. I developed significant testing anxiety, occasionally throwing up before and after pieces. The entire process left me physically and mentally drained to the point where I could barely bring myself to train for the entirety of my senior year. And while I am beyond grateful to row at Wellesley, I cannot say for sure if I would endure the same process again. Sadly, this is a pattern, as I know countless other rowers and athletes who have shared similar, or even worse, experiences.

I know that I run the risk of sounding hypocritical, as I have benefited significantly from the very system I wish to disrupt. But going through the recruiting process gives me the authority to say it isn’t always worth it. Athletic recruiting creates a biased admissions process that negatively impacts the wellbeing of young athletes. College athletics can be great, but athletic recruitment shouldn’t exist.

Despite all of this, it is unlikely that any elite college will end the practice of athletic recruiting. Universities are actively incentivized to admit students that will bring fame and prestige to their institution, and there is no better advertising than an NCAA title. College athletics are a multi-billion dollar industry built on exploiting young athletes, starting with athletic recruitment. However, that doesn’t mean that something cannot be done to address this. More resources should be offered to community sports programs to help them overcome the physical and financial barriers in sports. More support should also be allocated to maintaining the physical and mental well-being of young athletes. These measures should extend up to the collegiate level where universities should do more to support the specific needs of students of color. While increasing access to more public health and sports programs may not solve the larger problems with athletic recruiting, it is an important first step.