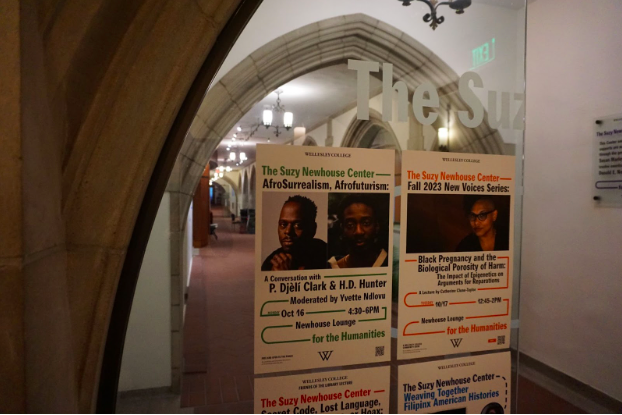

“What’s up, y’all!”: Afrofuturist author H.D. Hunter greets the crowd filling the Newhouse Center lounge. He is met with a rumbling chuckle from the audience, smiles cracking faces – an early indicator of the success of the event. The event, artfully titled ‘A Night of AfroSurrealism and Afrofuturism with P. Djèlí Clark and H.D. Hunter,’ was a celebration of Black Speculative Fiction Month, moderated by Wellesley College’s very own Newhouse Visiting Assistant Professor of creative writing, Yvette Ndlovu, hired last year with resounding enthusiasm from the English department.

“We were really lucky,” Marilyn Sides, an English professor who was part of the hiring process, remarked. “She’s somebody who really supports other writers. She writes in this genre herself, and obviously is very connected.”

Sides was particularly excited about the background in black speculative fiction – a genre under which falls the subsects of afrofuturism and afrosurrealism – that Ndlovu brings to the department. And bring it she has. Every aspect of the talk was carefully crafted and executed so that audience members and authors alike were able to discuss and derive a greater understanding of black speculative fiction through the lens of two forces within the genre.

“I wanted two speakers that would be in conversation together to talk about science fiction and AfroSurrealism and Black speculative fiction, and I think P. Djèlí Clark and H.D. Hunter were just the perfect conversationalists together,” Ndlovu said.

The two authors were a pairing which allowed for multiple perspectives to be in communication. P. Djèlí (pronounced “Jel-ee” or “Jah-lee”) Clark writes for more mature audiences and has an established career with novels like “Ring Shout,” also serving as an assistant professor in the department of history at the University of Connecticut. Meanwhile, Hunter is an up-and-coming YA writer whose debut novel, “Futureland,” contains elements of the graphic novel. Hunter, who has a background in indie publishing, was inspired in part by his experience growing up.

“I’ve been writing for a long time. Since I was a kid, just kind of for fun or through whatever outlets that the school had. Simultaneously, I was always consuming speculative media. Whether it be science fiction or fantasy, cartoons, the stuff that I liked to watch and read was always in that realm. But it was not always representative of black Americans and there wasn’t a ton of diversity of kinds of culture and ethnicity in general in the media that I was consuming when I was a kid,” Hunter said. “But there was one show. It’s called ‘Happily Ever After’… I loved that show, and I think that my first inclination of ‘I can write a story that’s a fairy tale or a fable or a fantasy or science fiction and put myself in it or put people that look like me in it’ probably came from that show. But it wasn’t until way later after high school after college that I sort of made the connection and started doing it in an intentional way.”

For both authors, history and homelands play a major role in their work. History is also an important element for the black speculative fiction genre as a whole. Ndlovu notes that the terms underneath the black speculative fiction umbrella are, to an extent, fluid. She says that it is up to the authors to define where their pieces may fit under that umbrella, whether labeled “Afrofuturism,” “African surrealism,” “AfroSurrealism,” “Africanjujuism” or something else.

“All these different terms that have come up help to capture the diversity of the black community. And I think that’s a good thing that someone like me from Zimbabwe and southern Africa can find space in the genre. That somebody like [Hunter] who’s from Atlanta, Georgia, as well as P. Djèlí Clark, who has roots in the Caribbean in Trinidad and Tobago, that we’re from completely different places, but we’re able to find a home in speculative fiction,” Ndlovu said.

This gets at one of the most poignant points of the talk itself: part of the value of the event was having faculty, students and authors in conversation, to bring together multiple perspectives in order to conduct a productive, meaningful conversation. A large part of this was driven by Ndlovu’s own experience and knowledge of the authors themselves, leading her to ask layered, complex questions – which Sides emphasized: “Oh they were just brilliant!”

“My personal definition of AfroSurrealism is that it tells the narrative of the contemporary black experience,” said Ndlovu. “AfroSurrealism taps into the absurdity by using horror and magical realism to think through that lived experience and Afrofuturism is doing similar work. Only that it’s kind of speculating on how the present and the past will shape Afro futures.”

Both authors at the event incorporate past and future elements to think through very real traumas and issues, and black speculative fiction is a genre gaining popularity for its ability to do so on a wider scale.

“I feel like we’re watching something amazing develop in real time,” said Hunter. “It’s been developing so long without us being able to watch as closely … writers have been doing this for generations that just weren’t in the limelight enough. And so it felt really humbling to be a part of an event that is focused on those things. And it also felt great as a takeaway to say this is just a starting point.”

Although on a small scale, this event is indicative of the growth in popularity black speculative fiction is seeing, as Hunter points out, the genre has a long – if buried – history. Ndlovu details her own experience as a Zimbabwean whose family and community uses mythology to better understand and process real-world issues.

“Zimbabwe was under a 40-year … Mugabe dictatorship, and we used the concept of immortality to think through what does it mean to live under absolute power,” Ndlovu said. “I’ve taken that with me and used things like immortality, mermaids and spaceships to think about the real world and real structures in the world and systems of injustice.”

One thing touched on in the talk was the effectiveness of the genre as a way to work through historical traumas, particularly in Clark’s novel “Ring Shout.”

“Using speculative fiction weirdly provides a little bit of displacement. It’s not right now, it’s not that exact history,” Sides said. “By having that, you get a chance to get into it in not the usual way … It’s not palatable. It just gets you out of this conditioned reflex that you have to these things.”

Black speculative fiction is growing through multiple mediums – through film with the release of “Black Panther” and through music with artists like Janelle Monae. And with that growth, definitions of these subsects gain more nuance, a fact Clark pointed out during the talk as a positive sign – if sometimes difficult to navigate.

“My favorite avenue to revisit the past is definitely Afro-speculation,” Hunter said of the genre, going on to recommend all of Clark’s works. Clark was an inspirational force in the industry for Hunter and one of Ndlovu’s teachers at the Clarion West Writer’s Workshop. Ndlovu and Hunter have previously collaborated on a grassroots collective supporting black speculative fiction writers through mentorship and creative writing classes, called Voodoonauts. Hunter has been working in the black speculative fiction genre in multiple capacities. Perhaps part of what makes him successful in these various roles is his intentionality. Each character, chapter, and project carries with it specific meaning and purpose.

“I hope that folks can see what I’m trying to embody in this newer generation of publishing professionals,” Hunter said. “The publishing industry is big and old-fashioned and unwieldy. I feel like a disruptive force a lot of times and I’m always proud of it, but sometimes, it’s not fun at all. Sometimes it feels like walking backwards, but I think that being transparent and honest about my experience as somebody who is trying to create art for a living … I want to share what that feels like to people who might have that same aspiration or maybe are just curious.”

Hunter details the differences he has noticed moving from indie to more major publishing: kids, who remain his primary audience for their “Futureland” series, are not included in test groups. In the same vein, adults are typically the ones securing media for kids, so Hunter explains that they must walk the marketing line between staying true to what kids will read versus what adults will buy. Part of his mission is to make his novels accessible and engaging to a group who tends to drop out of the reading realm: tween to teen boys. Generally, Clark, Hunter, and Ndlovu all are seeking to expand the genre of black speculative fiction, making it more visible and accessible to a variety of groups – including in academia.

“I’m just hoping that people read more widely, as well as experiment with speculative fiction themselves. I think speculative fiction, especially in academic settings, is sometimes viewed as not a serious form of literature,” Ndlovu said. “But I think just hearing from Clark and how history and all his research has informed his fiction shows that it’s rigorous. So I hope people are encouraged to play with ghosts and mermaids and not feel like they can’t do that in an academic setting. They can certainly do that at Wellesley.”

Hunter, who has a sequel to his debut novel coming out on Nov. 7, called “The Nightmare Hour,” and an AfroSurrealist short story coming out Nov. 13 from the Porter House Review, emphasized his gratefulness for Wellesley, the Newhouse faculty and staff, Ndlovu, Clark, and the full audience who chose to attend. This Wellesley event has the distinct honor of being Hunter’s first college book talk: perhaps a testament to the ever-widening avenues which black speculative media is carving out in the literary world.

For those looking to get into black speculative fiction, Ndlovu and Hunter gave their recommendations for black speculative fiction in multiple media:

Collections and novels:

- Ring Shout by P. Djèlí Clark

- Fifth Season by NK Jemisin

- What it Means When a Man Falls from Sky by Lesley Arimah

- Chain Gang All Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei Brenyah

- And This is How to Stay Alive by Shingai Njeri Kaguna

- Jackal Jackal by Tobi Ogundiran

- Pet by Akwaeke Emezi

- Binti trilogy by Nnedi Okorafor

- Dread Nation by Justina Ireland

Films:

- Get Out, by Jordan Peele

- Sorry to Bother You, directed by Boots Riley

- I Am A Virgo, by Boots Riley

- Atlanta, by Donald Glover

- They Cloned Tyrone, directed by Juel Taylor

Music:

- “Metropolis EP” by Janelle Monae