“Things can turn on a dime.”

This statement by Sandy Sugawara — former journalist and foreign correspondent who now works as a senior advisor to the US Agency for Global Media — was a key takeaway from her lecture on [date of the event], where she spoke to Wellesley students and faculty alike about her book, “Show Me the Way to Go to Home.” In it, she discusses the impact of Japanese internment camps — isolated areas where suspected “conspirators” were kept as a fear-mongering tactic — in the United States during World War II, and the trauma they left many Japanese Americans with after they were disbanded. For Sugawara, this idea of everyday life “turning on a dime” is important for recognizing the struggles of the past, but it also provides a warning for the future: in our often-volatile political climate, things can shift from normal to chaos in the blink of an eye.

Sandy Sugawara was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, to Japanese American parents. She found herself drawn to journalism early on, and after hearing about Wellesley College, she toured the campus and fell in love. While at Wellesley, Sugawara pursued journalism and political commentary, and participated in the Wellesley in Washington program. While in D.C. for the summer, she interned with Senator Daniel Inouye, the very first US Representative from the state of Hawaii. After graduating, she got a job working for Congressman Norman Mineta. From there, she entered the field of journalism and international media operations.

Despite her resounding success in the political and global media world, Sugawara stayed close with her family, and it is through her mother and father that she learned the true depth of the trauma Japanese American internment camps inflicted upon them. She recalls sitting with her ailing mother towards the end of her life, when, out of the blue, her mother sat bolt upright and started firing off questions. She asked her daughter why the government forced Japanese Americans into the camps in the first place, why nobody had rushed to aid those trapped in the camps, despite the lack of evidence against them, and why, more than anything, it had happened so quickly and without any significant recognition. She was especially worried, after seeing the news about insurgency in 2019, that this could happen again, and begged Sugawara to “do something to help those dear, dear children.” This startled Sugawara; her whole life, her parents had never openly discussed the significant impact the camps had on their psyche. This sudden outpouring of emotion by her mother, combined with camp documents and remainders of camp life she found a few months later, pushed Sugawara to visit the site her parents had been at during their detainment.

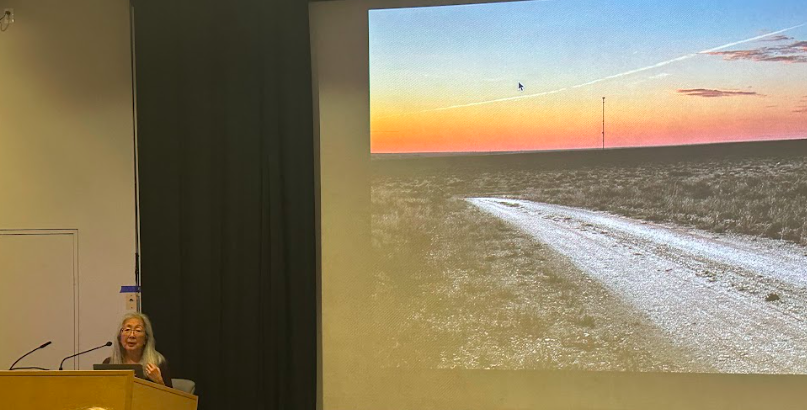

Sugawara visited the Amiche camp in Colorado first, which was the camp her parents met at. She harkened back to how she felt, standing in the dust of where her family had begun,saying, “I really felt the spirits talking to me through the landscape.”

Sugawara had always valued photography and the way photographs could transport people as well as convey an emotion that transcended words; she had even made a makeshift darkroom in the Stone-Davis kitchen during her time at Wellesley. It seemed only natural, therefore, that she photographed a place that spoke so deeply to her. But she didn’t want to stop there.

Sugawara and her colleague committed themselves to seeing all ten camps in the United States that had held Japanese Americans. What they encountered was an untapped depth of history and trauma that reflected the volatility of the American political system in times of war. Confronted by the ruins of barracks, of headstones for babies and soldiers alike, and by domestic moments like a baseball diamond remaining in the dirt, Sugawara knew she had to share her connections with the wider public. She decided to publish “Show Me the Way to Go to Home” with the hope that it would not only educate those who read it, but give them perspective into an area of American history that is often overlooked or repressed. She also wanted to emphasize the hard truth of the Japanese internment camps: the country was not made safer in any way by their existence, and yet they continued to remain operational.

So what is the great takeaway from Sandy Sugawara’s published work? The author herself leaves that somewhat up in the air, hoping the photographs will affect her viewers in unique ways. But for Wellesley students in particular, Sugawara hopes that the book will inspire them to keep an eye on the political climate around them. In a world of instability, Sugawara argues that we have a responsibility to make sure injustice doesn’t go unaddressed.

“This is a body of incredibly talented [people], and if they have a story to tell, they should tell it”; in other words, if the “turning of the dime” ever occurs, we should be ready to not just speak on it, but also to work on stopping that turn in the first place,” Sugawara said.