On Wednesday Oct. 18, Wellesley hosted Dr. Lisa Fagin Davis, a prominent scholar of medieval manuscripts, to discuss the mysteries of the Voynich Manuscript. Hosted in the Suzy Newhouse Lounge, the event was attended by Wellesley’s sizable community of manuscript and rare book enthusiasts.

Davis has been the executive director of the Medieval Academy of America since 2013, and has cataloged medieval manuscripts at the Museum of Fine Arts, Yale University, Tufts University and Wellesley College, among others. She specializes in paleography, which is the deciphering of ancient manuscripts and analysis of historic handwriting.

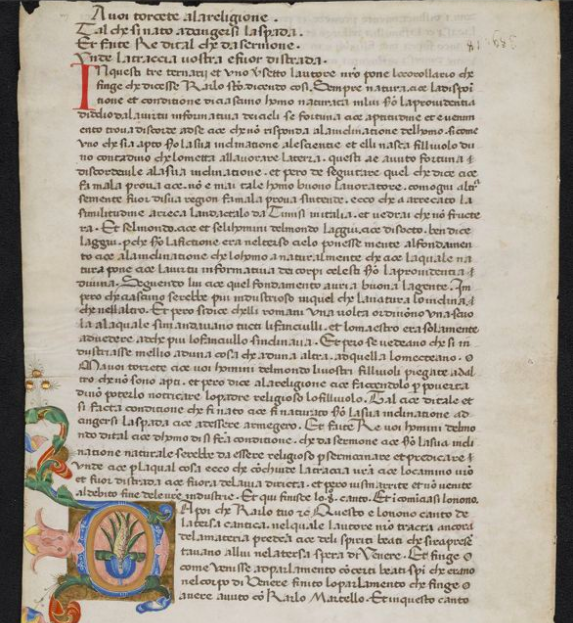

The Voynich Manuscript, which dates back to the early 1400s, is an enigma: written in a nonexistent and indecipherable language, it features seemingly scientific illustrations of plants, beasts, zodiac signs and naked women. Its author and origin is unknown. It allegedly passed through the hands of Emperor Rudolph II of Germany, Jesuit scholars, American rare book sellers, and finally to Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where Davis first “met the Voynich” as a junior in graduate school.

The text fascinates and puzzles scholars and the public, and has generated more than its fair share of conspiracy theories. Davis explained the methods linguists use to show that the “Voynichese” language of the manuscript is a real and evolved human language. Unlike fantasy languages like Elvish or Klingon, Voynichese passes Zipf’s Law, a linguistic rule showing that in a natural language, the most common word is twice as common as the next, and so on.

At the lecture, Davis presented her studies of the images and glyphs used in the texts, and her theories on the writers behind it. Her work has found that five distinct scribes wrote the text, two of them writing in their own unique dialects of Voynichese. She remains hopeful about the possibility of someday understanding the manuscript’s mystery.

“I think we’ll get there. And that’ll be just the beginning, like, that’s not the end! Once you can read it, then you’ve got a whole new world to explore! You know, that’s not the end of the puzzle, I think,” Davis said.

Davis’s visit was arranged by Ruth Rogers, the Clapp Library’s Curator of Special Collections. As curator, Rogers oversees Wellesley’s own collection of over 40,000 items, which originated from the collection of Wellesley founder and rare book collector Henry Durant.

Rogers met Davis at a conference of manuscript scholars. Rogers and the Friends of the Library (a group that supports the work of the Clapp Library) decided that the College’s collection of 40-plus medieval manuscripts needed to be cataloged by a specialist, and they hired Davis to do so.

“It took her more than a year to catalog them, and now they’re really professionally cataloged,” Rogers explained. “People write to us from everywhere, all over the world. Many of them have actually been digitized, thanks to LTS’s commitment to preservation and access, so people can actually study them from anywhere.”

One attendee at the lecture was Maggie Erwin ’23, a Wellesley alum who now studies with Davis at Simmons University’s graduate program. Erwin talked about how Wellesley’s unique connection to the world of manuscript archiving led her to pursue a path in archival library sciences.

“Because of my work in special collections here, and in the book arts lab, I was very interested in how books were made, and that’s kind of how I became interested in the history of books; and then Wellesley has an incredible manuscript collection,” Erwin said.

Erwin encourages Wellesley students to get involved with this aspect of the school.

“I think that it would be great if more students could be involved because as Professor Davis was saying in her lecture, there’s so much we don’t know, and that is true of Wellesley’s collections too; there’s tons of stuff to be researched.”

As for Davis’s lecture, Rogers agreed it was a success, well-attended and captivating.

“As erudite as she [Davis] is in the knowledge that she has, she is also equally generous in helping anyone who’s interested in her field. She’ll answer your email, she’ll answer a tweet, she’s always ready to listen to anybody and help anyone,” Rogers said, later adding with a smile, “She’s got some arcane specialties, like Star Wars memorabilia.”

Davis’s singular overlap in interests was evidenced in the slides she showed of her collection of Voynich items, including a canonical comic strip in which the Voynich Manuscript was stolen from Yale and had to be recovered by the Avengers.

Davis said she enjoys hearing people’s theories on the manuscript, telling the story of a woman who believed it was a crochet pattern and actually “crocheted” several pages of the mysterious text.

She also mentioned her own predispositions, saying, “In my heart, what I want it to be — I will whisper to you what I want to be, which is that I really want it to have been made by a community of women, who recorded their knowledge for future generations. That’s what I hope it turns out to be.”

However, she notes the importance of exploring the artifact with genuine scholarly curiosity.

“When we approach an ancient object such as the Voynich manuscript, we tend to bring our preconceptions with us to the table,” she said. “The more we burden the manuscript with what we want it to be, the more varied the truth becomes. To truly understand the past we have to let it speak for itself. The Voynich manuscript has a voice, we just need to listen.”