To most, poetry is just words on a page, illuminating in pattern, cadence, and diction a message or a story. But poetry remains two-dimensional, a concept that exists solely on paper, and only to those who actively work to interpret it.

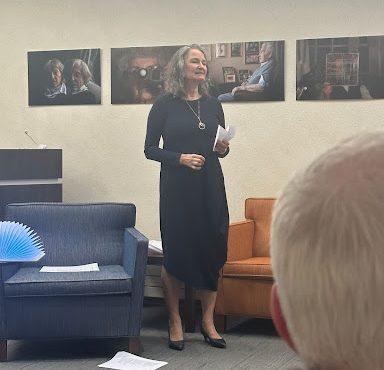

This, however, is not how award-winning poet Vera Pavlova views poetry, and it is not how she presented her latest poetry collection, “The Line of Contact.” To her, poetry is meant to be immersive, throwing her audience completely into the story and making them feel as if they are almost living the poem rather than just hearing it. In doing so, she impacts her readers and listeners on a deeper, more intimate level.

Vera Pavlova was born in 1963 in Moscow, Russia. While in Russia, she studied first at the Oktyabrskaya Revolyutsiya Music College — also known as the Kiryukov Music College — and then at the Gnessin Academy, specializing in the history of music. It is perhaps her musical background and her understanding of rhythm that inspired her to pursue poetry; whatever the reason, she began publishing after she graduated and never looked back. Her three collections before “The Line of Contact” (2023) are “Album for the Young (and Old),” “If There is Something to Desire: One Hundred Poems,” and “L’ Animal Céleste,” written in 2017, 2010 and 2004, respectively. She has also written opera librettos, music lyrics, and published essays referencing musicology. One of her most famous works, called simply “Four Poems,” was published in “The New Yorker” in 2007.

The reading, or more accurately, the performance, began in complete darkness. Pavlova would first read off a poem in her native tongue, Russian, using a slow and melancholy voice. She spoke solemnly, and her two student interpreters then read the English version with the same tone. They were poems of war and wartime, how it felt to exist when your world was crashing down around you, and phrases like “the secret lines that had taught us/how to cry” and “Trying daily to persist/washing blood stains off the flag” spoke to the bleakness and blackness of war. There was very little light, an intentional choice by Pavlova to keep her audience surrounded by a bunker-like cocoon of darkness.

Once she had finished the first section, she stood up and began lighting small paper lanterns, each with a poem upon it. The small lights lit up the darkness, and in the center of the room, Pavlova began reading each poem in Russian before lifting it aloft, passing it to one of the listeners, and having them read the English translation. Pavlova’s choices of recipients were not random either; she appeared to contemplate each choice carefully. This is perhaps because the poems were about memory and dreams. Each had a sense of childlike wonder to them, tinged with the residual bitterness from the first section. Certain lines like “a trip to cloud nine” and “days of sunshine everywhere” elicited messages of times long past, but not forgotten, with a reminder of war underneath the surface.

Finally, Pavlova signaled for the lights to rise, and then reached behind her to what had before been unassuming scraps of paper. They were revealed to be paper airplanes, carefully folded, which she then launched into the audience. A stark contrast from her last chapter, which had all been intentional; this could only be the most random of audience selections, with the poems flying at random to members of the crowd. This mimicked her poems in this third section — random but beautiful. They all seemed to be fortuitous, though still edged with both war and memory. They helped provide a brilliant end to her performance, which started in the intentional and pressing dark, and then was punctuated by sparks of light before finally illuminating the entire scene.

Following her luminescent finale, she bowed, and then was seated for questions. When asked about contemporary poets and their impact on the world today, she said, translated from Russian:

“When all around, there are explosions, their voices can become even louder … you must remember how Orpheus, with his song, made the three-headed dog stop barking … sometimes it feels as if we are singing to make the dog stop barking.”

She then went on to say, however, that there is not always a happy ending; the voices of dissent, especially those in art, can often be drowned out or silenced completely by war. While she may be referring to the ongoing conflict in Russia and Ukraine, this is in no way an isolated experience. Hopelessness, or darkness, can be all-consuming, but those little pockets of light can chase darkness away. So Pavlova not only performs to engage, but also to inspire; she hopes that between the lines and light, we can be invigorated to create something beautiful in the darkest of times.