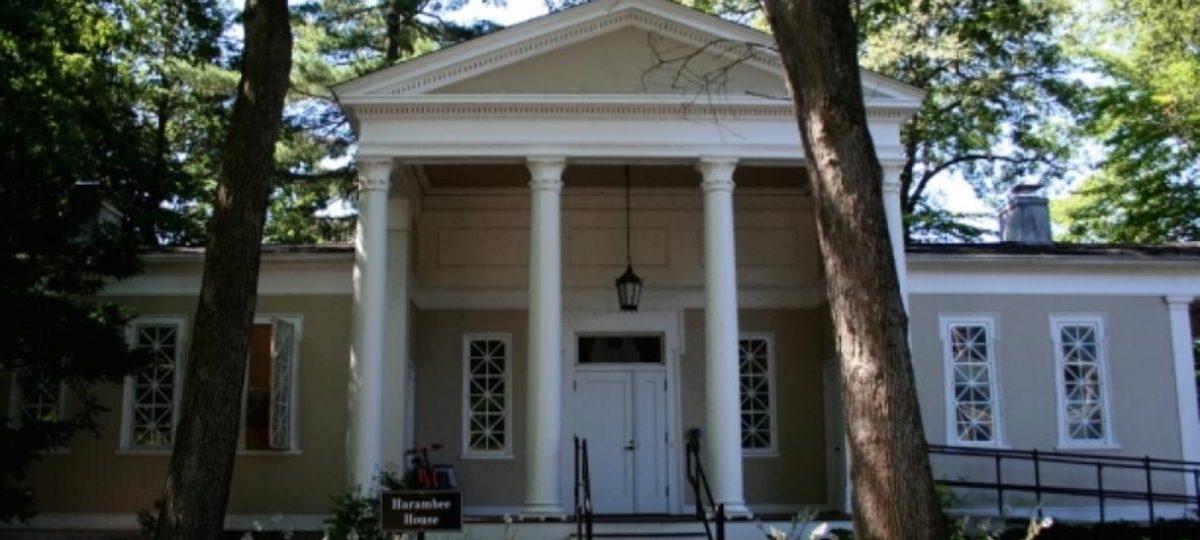

Since its opening in the year 1970, Harambee House has provided students of African descent at Wellesley a space to collaborate, celebrate culture and cultivate a community. This year, to kick start Black History Month celebrations, the House organized a talk by Professor Sabine Franklin on Feb. 1, the first of many events organized as part of the celebrations.

Franklin is a Mellon postdoctoral fellow at the Africana Studies department at Wellesley. Having completed her PhD in economics at the University of Westminster, Franklin serves as a fellow for the Governance and Local Development Institute at the University of Gothenburg and is a recipient of the 2022-2023 AAUW Postdoctoral Research Leave Fellowship at Yale University. Franklin’s interdisciplinary research focuses on how low-income countries address public health emergencies.

The talk, hosted at Harambee House, began with an overview of the global evolution of Black History Month by Franklin. The overarching theme was an emphasis on Black scholarship and celebrating Black voices. Reflecting on her time pursuing a PhD in the United Kingdom and her experiences with higher educational institutions in the United States, Franklin noted the increasingly crucial role of academia in advancing a greater understanding of Black history.

Furthermore, Franklin commented on the skewed recognition of Black scholarship across continents. She further explained the significance of historic events like the Black Lives Movement in transforming such trends.

“[When] I was there, there were 24 Black female professors in the entire UK. Compare that to Columbia University … they had 30 Black female professors just at that one university. So, one Predominantly White Institution had more Black female professors than the entire United Kingdom,” Franklin said. “Now, after 2020, with George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and the Black Lives movement becoming transnational, I noticed that Black scholars were finally being recognized for their contributions and were being promoted.”

Franklin shed light on the contributions of the Black community that helped shape US history as we know it today and how Black perspectives are often excluded from the larger conversation on US history. In doing so, Franklin discussed the tendency of higher educational institutions to treat African American history and US history as mutually exclusive to each other. Franklin further commented on how she would approach teaching US history if given an opportunity to do so.

“When I was an undergrad, you had [courses like] US History One, US History Two. And then, separately, you have Black history … looking at how Black Americans contributed to the shaping and founding of the US, it should be more integrated than that,” Franklin said. “But as someone who’s been a student in higher education, and now working in higher education, I also see more of the politics behind that. We still have generations and generations of scholars who were just not trained in that way. Speaking from my experience, as a history student … I was not trained to see these perspectives as mainstream.”

In discussing next steps as part of an antiracist, decolonial strategy, Franklin reinstated the importance of unlearning attitudes and practices that continue to be taught as part of courses on economic and political development today.

“We cannot have good policymaking if we cannot acknowledge the starting point that European countries had, and Black and Brown countries did not,” Franklin said.

Franklin concluded by urging individuals to reflect on what it means to celebrate US independence and the role that Black History Month plays in educating today’s youth on the achievements of the Black community.

“When we speak of American Independence on July 4, 1776, ask yourself – who became independent on July 4, 1776? Black Americans did not. Indigenous people did not. Many other communities did not,” Franklin commented.