On Feb. 27 Professor Eric Jarrard and Jordyn de Veer ’24 presented and discussed their research for Professor Jarrard’s upcoming book “The Exodus and Law in Monuments and Memory.” The talk is part of a new speaker series presented by the religion department entitled: New Research in the Study of Religion.

Jarrard is a Scholar of Biblical Studies with a focus on the Hebrew Bible. He began the lecture by describing his evolution as a scholar, beginning in his hometown, Richmond, Virginia, which was described as having the “distinct dishonor of being the capital of the confederacy.” The town, which is full of (confederate) monuments, shaped his thinking about the importance and meaning of these structures. His upcoming book is driven by a desire to explore how monuments in the ancient world affected the writers of the Bible, as he explained, “how do monuments affect the way we think about the past and the way we transmit these stories?”

He highlighted how those who study or engage with the Bible often attempt to parse out the history from the law, but he sees them as inseparable elements. He explained that the legal code of the Bible is almost inconceivable without Exodus, which follows a long history of monuments that explicitly link history with law — “laws and decrees tend to be commemorative … and also mark specific events.” Jarrard argued that the Bible mimics the events of the monuments around the writers of time, lacking adequate resources to construct physical monuments of their own, Biblical writers constructed a textual monument.

The exploration and discussion of these monuments is vital to his book, but many of them are owned by or located in European museums, and to obtain even a photograph for use requires an exorbitant fee. Jarrard noted that his “ability to understand monuments relies on using exploits of colonial activity,” and he wondered how to reckon with this for his book.

“I can’t divorce my project from [its] ethical implications … the objects I study are only available because of exploitation of the Middle East, which was often justified using the Bible [itself],” Jarrard continued, “My work is paradoxically grounded in postcolonial theory … I try to separate the work I’m doing from monetarily incentivizing museums to hold onto objects of contested origin … [I want to] push against what I think of as orientalist impulses which want to cleave the Bible from its context in the Middle East.”

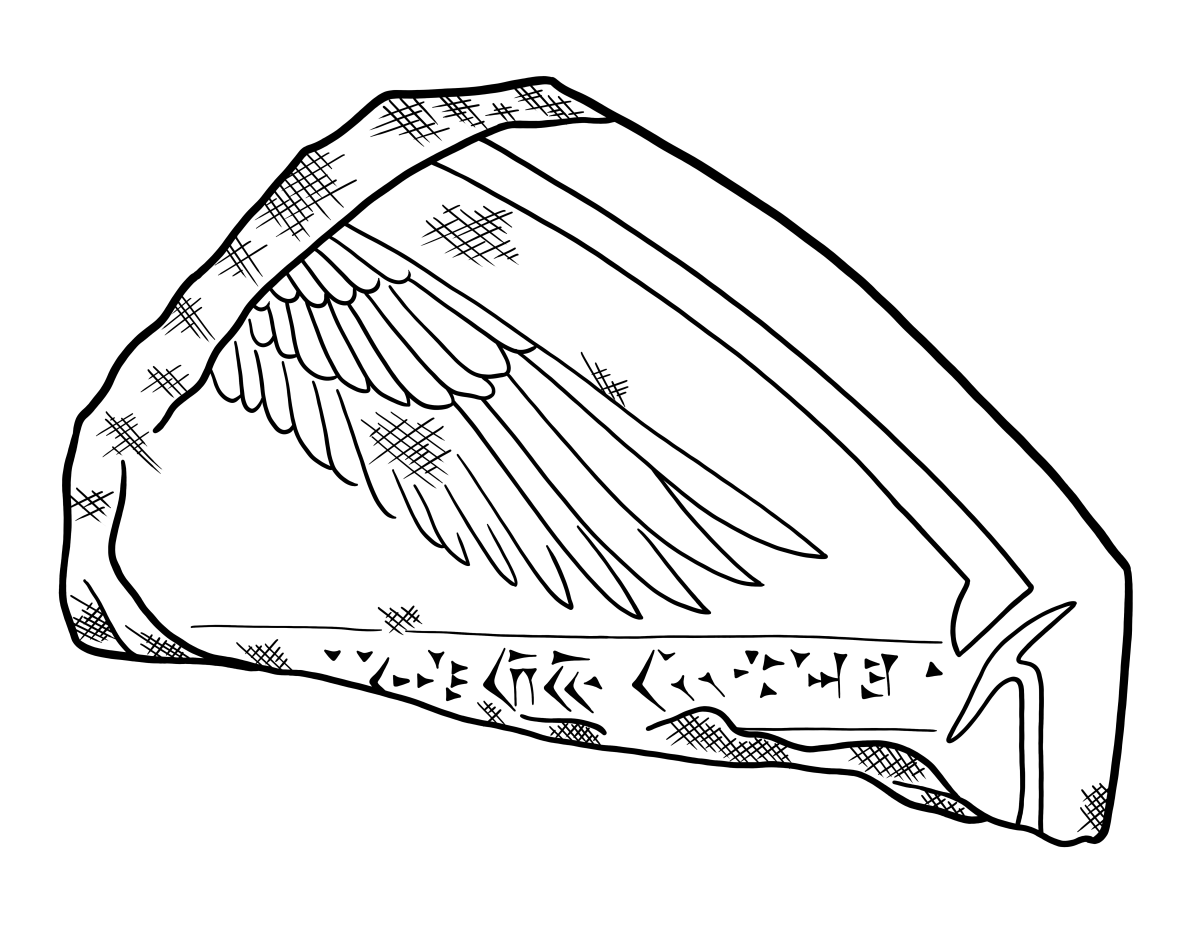

Jarrard and de Veer worked together to develop a new way for these monuments to be presented in the book, and settled on de Veer (who has artistic background and experience) drawing the monuments. De Veer explained in their portion of the lecture that this had the added benefit of increasing legibility, as monuments are often large, damaged and old.

Before coming into this role, de Veer had taken several classes with Jarrard, and the two have developed a close relationship. But de Veer explained that, “this is the first time that I’ve really been able to incorporate my academic interest of religious studies with my art.”

The process of creating the drawings was labor intensive, especially at the beginning as Jarrard and de Veer worked together to craft a unique style, with de Veer sometimes creating as many as ten different versions of a drawing. Although tedious at times, de Veer explains how much they have enjoyed the undertaking.

“It has been really inspiring, because it just shows that you don’t have to do the predetermined thing. You can go outside of the box and think about reparative and critical thinking that goes beyond the norms of what academia has instilled,” de Veer said.

The lecture was well received and one of the Student Administrative Assistants for the religion department, Ella Kromm ’24, commented on how much she enjoyed the lecture.

“Both of them did a really great job presenting …and making it so people could understand, even if they weren’t coming from the background of a religion major or Biblical Studies,” continuing, she said, “[de Veer’s] artistic talent, and their ability to recreate these monuments … it was so beautifully intricate, all the details that they were able to incorporate.”

De Veer also noted how the research process has brought them back to Wellesley, and has encouraged them to think about the College’s place as a community within this scholarship.

“He [Jarrard] did a bunch of research on a piece that the Davis Museum owns. He looked at the provenance of it, because it didn’t have any record … It stirs the thinking process about where, even at [a small institution like] Wellesley, we stand in the colonial ramifications of looting and the diasporic element of what comes after that,” they said, continuing, “ … I think that it’s something that I’ll carry with me, the spirit of pressing back against that convention of what academics and what scholars are supposed to do and what they’re supposed to look like.”