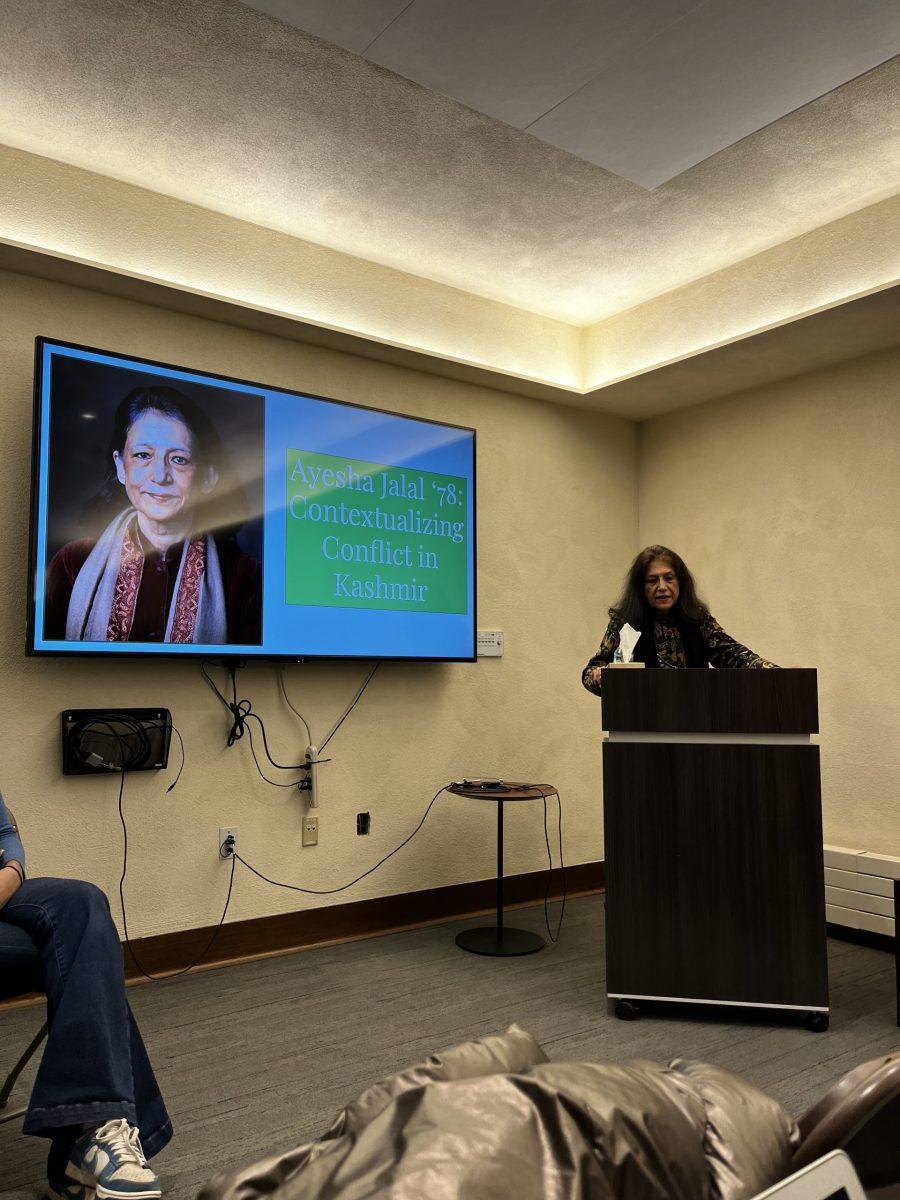

On March 28, Professor Ayesha Jalal ’78 led a fireside chat hosted by the Wellesley Association for South Asian Cultures (WASAC), titled “Contextualizing the Conflict in Kashmir.” Jalal is a Pakistani-American historian of South Asia, and is known for her work on Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. Her book “The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan,” was a pioneering work that discussed the events and causes leading to Partition. Jalal noted to The News that the causes of Partition were understudied when the book was published in 1994, and still remains so.

The format of the event hosted by WASAC was a Q&A session with some questions from WASAC e-board members to start with about the context of the current relationship between Kashmir, India and Pakistan, as well as the timeline of events that have led to the present day. Since the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, Kashmir has been a disputed territory with claims to it laid by both India and Pakistan, and is one of the most militarized zones in the world. Jalal explained the timeline of events that have led up to today, noting that the biggest blow to freedom in Kashmir was the abrogation of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution by the current government in power. Article 370 afforded Kashmir a limited level of autonomy of self-administration, except in laws related to finance, defense, foreign affairs and communication. Article 35A, under Article 370, specifically empowered state lawmakers to ensure special rights and privileges for residents of the state, denying property rights to non-residents. With the abrogation of Article 370, non-Kashmiris are allowed to buy property in the region, and this is a particular point of concern for the Muslim-majority state and population.

Jalal gave some of this context and timeline, and the Q&A began with some questions from WASAC e-board members before the floor was opened to all attendees of the event, who asked a range of questions about potential solutions for the current situation, the parallels between Palestine and Kashmir, and the impact of propaganda on how Kashmir is viewed in India, Pakistan and around the world. Professor Jalal also invited some of her own graduate and undergraduate students to speak on their experiences as Kashmiris and also as experts in their own right.

Kashmir, for as long as it has been a point of contention, has been referred to as a religious conflict, but Professor Jalal insists that that is not the sole or even most important issue relevant to Kashmir. Jalal’s insistence that religion was not the only cause of Partition goes against many of the narratives that have existed around the causes of Partition. She makes a distinction, specifically in her book “Self and Sovereignty,” between religion as faith, which is more personal, and religion as identity, which is more publicly identifiable.

“Any understanding of history will tell you that while religion was always important, … nobody had fetishized it to the extent of the colonial category, that you were just monolithically Muslim,” she said in an interview with The News.

To Jalal, the most pressing issue in Kashmir is the military occupation, which rejects the right of the people of Kashmir to self-determination. The current system in place is one that follows the system in place during British colonial rule.

“Oppression learned from the colonial state comes too easy,” Jalal noted.

Jalal was also asked about the parallels between Kashmir and Palestine, and she explained that while she thought there are definitely parallels, there is much more religious tension in Israel and Palestine.

“There are colonial structures that the British created in Palestine that are now being recreated in Kashmir to control the people, and there are also similarities in the militarization as well,” she said.

The problem with Kashmir is also how people view the region to begin with, according to Jalal. Viewing the current situation solely through the perspectives of India and Pakistan is limiting, since the nation states are largely viewing this as a land dispute, rather than an issue for the people of the region.

“There’s a tendency to see things through the nation-states. So long as you see it through the perspective of India and Pakistan, there is no solution,” she said. “There is a possibility of a people’s approach, but that is not being allowed [right now].”