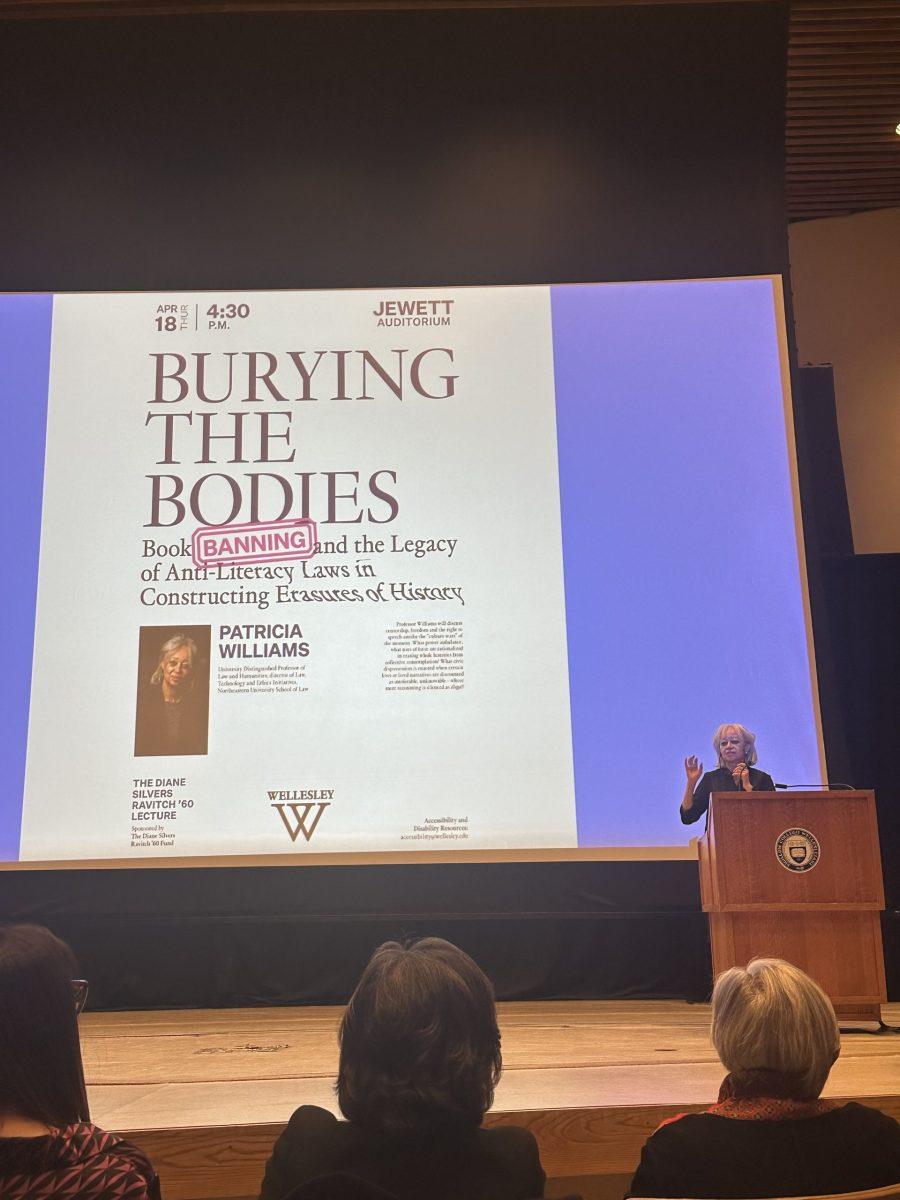

You would be hard-pressed to find a more hot-button issue in today’s school system than that of Critical Race Theory (CRT) — a term redefined initially by Christopher Ruffo, a senior analyst at the Manhattan Institute, for political purposes in a Twitter thread, which was then adopted by right-wing politicians. The threat of anti-CRT rhetoric on education, social justice and academic conversation is a crucial issue in today’s educational spaces, and in order to understand the threats to the future, we must also learn from the past. On April 18, Wellesley alum, Professor Patricia Williams ’72, spoke at The Diane Silvers Ravitch ’60 Lecture about the history of anti-literacy laws and their effect on social movements, her own experience at Wellesley College and the debate around Critical Race Theory in the modern age.

Professor Williams is a graduate of Wellesley College and Harvard Law School, and currently holds the title of University Distinguished Professor of Law and Humanities at Northeastern University. She teaches jointly at the School of Law and the Department of Philosophy and Religion and the College of Social Sciences and Humanities, and has published several times; her works include “The Alchemy of Race and Rights,” “Giving a Damn: Racism, Romance, and Gone With the Wind,” “The Rooster’s Egg” and “Seeing a Colorblind Future: The Paradox of Race.” She is also heavily involved as an alum, serving on the Board of Trustees, awarded the Alumni Achievement Award in 2000, and named a MacArthur Fellow. She has been discussing gender, race, literature and law in her field for years, and she reflects on what we can learn from the past, present and future.

When Professor Williams was at Wellesley in the 1970s, she says that there were only six African-Americans in her class year, and they were confined to their own rooms because “the school at that time, was worried about what parents from the south of the United States would think and would object to interracial rooming situations.” She often wonders what would have happened if she had been allowed to have a roommate who was unlike her, and what sort of discussions would have arisen if she had been able to have casual, constant conversations. She called it a “policy of exile,” and said that it was even more dangerous than allowing two distinct and opposing opinions to coexist with each other. She spoke about how her own son’s roommate brought a Confederate flag into the dorm room when he moved into college, but after sitting and speaking with each other, “they decided that they liked each other, basically. And they each approached each other with a certain sense of good faith.”

Professor Williams worries that we, as a modern society, have reverted back to the idea of division, or more importantly, lack of discussion. She says, “I worry that we’ve entered a moment in which you simply can’t talk about what is really hurtful. And if you do, there’s a way in which it gets pushed into … silence in a way that reiterates a certain kind of history.” She believes that reverting back to a society of silence reinforces, “Jim Crow’s legacy of racial retribution in this country,” and that to truly learn as a nation, open conversations must continue to be facilitated. She also brought up an incident in Michigan, where students held a mock-auction in a Snapchat group in regards to their Black classmates, and the way in which their punishment was pushed back on by the parents in the school district. She notes, “it is a sign of the confusion of this moment that condemning racist or bullying behavior is seen as the automatic and specific equivalent of being anti-white, and ethical of public hearings.” All of these instances prove that where there is conversation, there is understanding reached, and where there is not, hatred and misinformation festers.

This could not be any more apparent than in our current debates on Critical Race Theory. In the anti-CRT bills introduced by states, and the Project 2025 plan to nationally and legally ban all CRT language, Professor Williams says that these bills state that “no stereotyping by sex or race, no instruction that teaches any one race or sex inherently superior to another, no teaching that any individual is intrinsically racist or sexist or oppressive, and no teaching that anyone bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by members of the same race” is anti-CRT, when in fact, those are core tenets of CRT. There has been a political manipulation of CRT into a shaming and hateful educational strategy, rather than an educational one, because it brings up dark histories of racism in this country.

Professor Williams, through her own experiences and through her research and writing, has seen a shift in the education of America’s children. She sees a loss of historical learning, a sacrifice of truth for comfort, and a “disease” of intentional ignorance sweeping the nation. She believes that the only way to confront this epidemic is to look at our history, learn from it and begin to educate others on it; in other words, exactly what Critical Race Theory aims to do.

She ended her talk by discussing the impact Toni Morrison has on students, and the education she can provide: “[Morrison] wrote of the nightmare world of lost voices, where it is as though a whole universe is being written in invisible ink. She observed certain kinds of trauma visited on peoples are so deep, so cruel that unlike money, unlike vengeance, and even unlike justice, or rents, or the goodwill of others, only writers can translate such trauma and turn sorrow into meaning sharpening the moral imagination. A writer’s life and work are not only a gift to mankind, it’s a necessity.” One can only hope that this necessity is soon recognized by the nation, in hopes of preserving true education.