On the evening of March 28, Wellesley Asian Alliance (WAA) hosted an event entitled: Asia America Through Academia in honor and celebration of the 10th anniversary of the creation of the Asian American Studies (AAS) minor. The event was held in the Jewett Sculpture Court and featured a pop-up exhibition covering the history of AAS, and the collective action, organizing and protest that led to its implementation as a minor at Wellesley.

Emma Lee ’24, one of the co-coordinators of WAA (a position analogous to president in the non-hierarchical org), explained that as the 10th anniversary came up org members were considering how to commemorate the event. Lee had been considering and proposing ideas to the Eboard since her sophomore year, many of which were drawn from her passion for history and knowledge she had gained from the major.

“I wanted something to memorialize it. And as a history major, a really interesting way to do that is always through exhibitions or anything related to a museum. I feel like we have a lot of archives in particular that I would love to kind of resurrect, and show to the broader Wellesley community. We have archives that date back to when students were first protesting and demonstrating to get a full time Asian American advisor,” Lee said.

Lee’s instinct for a historical angle for the event proved successful, as it allowed WAA members to draw on their extensive archives, including articles from The Wellesley News, and ensure the legacy of the effort put into AAS could be taught to a new generation of Wellesley students.

In a pamphlet distributed at the event AAS was explained as an “interdisciplinary field that examines the lives, cultures and histories of people of AAPI descent living in the Americas. AAS as an academic field was born out of the movements for ethnic studies in the 1960s.”

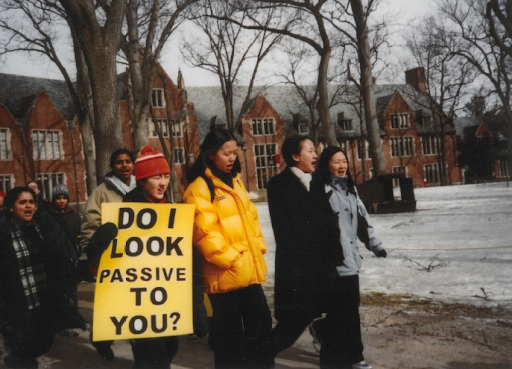

The exhibition began with a timeline of AAS at Wellesley. Drawing from decades of work by faculty and students to increase and support diversity both inside and outside of the classroom, the push for an AAS minor marked a turning point in 2001. Professor Elena Creef, who was hired in 1993 and is the only trained Asian Americanist faculty member, was denied tenure in 2001. This severely hindered opportunities for Wellesley students to be educated in AAS. The decision was a dismissal of the field at an administrative level and jeopardized its future at the college; not to mention the disregard for Creef’s immense popularity as a professor. This spurred Wellesley Asian Action Movement (WAAM) to organize a student protest of over 200 members. During this time, Wellesley had also been without a full-time Asian Advisor for two years, and the position offerings were so underfunded that they were barely able to attract any qualified applicants. Many Wellesley community members, especially students, saw this as a systemic denial of Asian voices, interests and concerns that ought be uplifted by the community beyond trivialized lip-service.

WAAM was eventually joined by Siblings Leading Action for Multiculturalism (SLAM), an org working for similar representation and support for Latine students. WAAM-SLAM’s collaboration was an essential moment in the history of the creation of AAS, as it drew students together and cemented the origins of solidarity that would allow for a collective push towards institutional recognition of ethnic studies.

Protests and organizing continued for over a year, after which Wellesley implemented the Korean Language program, the South Asian Studies program and full time positions for a Dean of students of Asian descent and of Latine descent.

But the work didn’t stop there. 13 years after its first wave of protests WAAM-SLAM II was formed, this time advocating ethnic studies more broadly, multicultural houses and, as an overview poster put it, “a redistribution of resources at Wellesley.” In 2014 the AAS minor was created. The exhibition highlighted not only the work of student activists in this achievement, but also the monumental efforts of faculty in the creation, organization and realization of the program.

Lee explained that this tracks with a long history of thoughtful collaboration between WAA and professors, and that professors had an especially important role in the creation of the AAS minor.

“Professor Kodera, of the religion department, was one of the founding members of WAA. And he’s also really helped shape the curriculum of Asian American Studies, along with Professor Yoon Lee, of the English department … [WAA doesn’t] know too much about how to create a minor. The professors know that. Back in the day, it took a lot of talking to the professors, getting their input, getting their letters and getting a paper trail from professors supporting us so that our own demands have some legitimacy, have some faculty support behind that. Something that’s really special about WAA is just how close we are with certain faculty members,” Lee said.

She explained that WAA is a “student organizing group, run by students for students.”

“We’re always thinking about what are Wellesley campus’ needs, what are the students’ needs, and then we hope, plan, execute and deliver projects or events that help kind of move forward any agenda we have … One of the pinnacles of my career as co-coordinator of WAA this year and my Eboard this year was raising awareness about issues pertaining to Palestine, and pushing informational mediums, newspaper articles, infographics, resources to students on campus. We hosted action hours for Palestine, in which we help students write letters to representatives, make calls, write emails, etc.” Lee said.

The event also featured short speeches from many of the professors, students and alums who had been instrumental in the creation of the AAS minor and WAA. There was a short archival video clip of students talking about the importance of the AAS minor during their protests over a decade ago. This moment came full circle with Lee talking about her own experience in AAS classes, and how much they had meant to her. She elaborated on this in her interview, saying:

“I saw Asian American psychology and it seemed like such a niche topic to me, I didn’t know that my own psychology could be so important to have a whole class dedicated to it … I remember one of those poignant moments was when the professor was talking about languages, and how language and affection is communicated very differently within culture. So he brought up the example, think about your immigrant parents, if you have immigrant parents, or if English is not their first language, if they say, I love you, when they hang up the phone, is that in English? Or is that in their native language? And then everyone in the room, we just went still … That’s an example of Asian American psychology, in the sense that we tend to, even in our language, hold a lot of value and [it] reflects a lot about our culture … it informs our personality and our psychology that impacts the way we behave. And that can impact the health outcomes, that can impact things like generational trauma, etc. That connection, just from the example of what your parents say, over the phone, showed me this untapped scholarship of Asian American facets of life … that, to me, was the first gateway into realizing oh, my God, my voice, my life, my experience actually matters. And they’re actually worth scholarship, and they’re worth being studied. And leaving the class, I felt like a lot of my own experience had been validated … a very broad impact of Asian American studies is that students learn things in these classes that they either take to the PhD level, they take to work in nonprofits, or they take to take back home, to open up these conversations about what they learned or to just inform their worldview,” Lee concluded.

The event also featured student works from AAS classes, as well as a spotlight on the classes themselves, which covered topics from fiction, popular culture, psychology, food, politics of beauty, labor and immigration and experience via the lens of Asian American studies. Essays in the exhibition included: “Not Like Other Chinese Moms: the Story of My Mom and Her Lifelong Immigration,” by Emma Illidge ’24, “Pretty Ugly: An Examination of Lookism and Neoliberalism in South Korea,” by Emma Lee ’24, “Illusions of Authenticity: Unraveling Cinematic Orientalism in ‘My Geisha,’” by Ashley Kwok ’24, “The Transformation of ‘Chinatown:’ Asserting Agency and Subverting the Model Minority through Placemaking” by Milena Zhu ’26, “Found in Translation: Translating Japanese Tombstones and Recreating Histories” by Natalie Osako ’26, “Transnational Migration and its Effects on Identity” by Anisha Rao ’23 and “The Intersection of Queer and Asian American Identities,” by Brenda Zhang ’26.

Event posters, promotional materials and presenters continually highlighted the importance of the intersectional work of collective action and protest in the creation of the minor, and the work that is still to be done. This largely includes expanding institutional support for ethnic studies as a whole at every level. Notably, there are currently still no Indigenous Studies professors at Wellesley. Beyond education, the event also served as a call to action for the Wellesley community, with the Welcome poster and informational pamphlets concluding:

“We are not done yet. We urge students to learn about the history of advocacy behind ethnic students, behind AAS and to continue the fight and memory … change is possible if we organize.”