There are doubtless many nooks of witchcraft on Wellesley’s Campus, but one I know for sure is on the fourth floor of Clapp Library in Special Collections. Curator Ruth Rogers and Associate Curator Mariana Oller have been my longtime co-conspirators in searching for holdings in Wellesley’s Special Collections that treat the topic of witches and witch hunting. Every time I teach PHIL200, Philosophy and Witchcraft, the students and I voyage to Special Collections to look through texts, ponder frontispieces, and dissect iconography. Armed with loupes and a spirit of exploration, we try to put ourselves in the space and time of historical authors and ask the question: what did they think about witchcraft? The articles below give you a sense of some answers in relation to seven early modern texts and one present-day artist’s book. I am grateful to Ruth and Mariana for their help this year and every year. I also wish to acknowledge the generosity of the Medieval and Renaissance Program, which recently funded the purchase of Pierre de Lancre’s text, which you will learn about below. And thank you to The Wellesley News for running this feature!

-Prof. Julie Walsh, Associate Professor of Philosophy

Origins of The Iconography of Witches

by Ella Warburg, Katie Adler, & Emma Fraser

The witch is one of the most iconic Halloween costumes of all time. Worn by young and old alike, the witch is a go-to, spirited costume. All you need is to be adorned in black, a pointy hat, a broom and, if you have one, a black cat, and boom: you’re a witch!

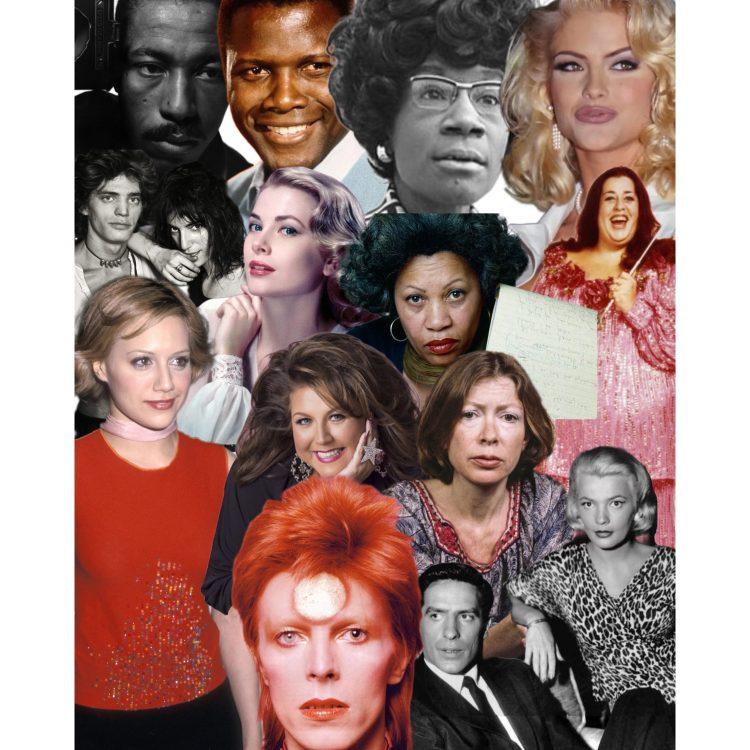

But where did this iconography of the witch come from? We visited Special Collections and dove into George Cruikshank’s “Plate 10: Witches Frolic” in his book Twelve Sketches in order to find out. Created in 1830, “Plate 10” depicts seven witches out at sea, surrounded by blackbirds with a horned devil in the waves and a white ship in the background. Two of the seven witches have the classic black pointy hats, two have black cats that are holding on for dear life, all are riding what appear to be barrel tops, one is looking towards the reader with mischief in her eyes, and all are flying towards the devil. The black birds behind the witches bring a further menace to the picture, as they are commonly associated with being both familiars of witches and omens of death. While the wind appears to be blowing in multiple directions, it all points towards the devil in the sea. This picture effectively screams “evil magic” through its typical portrayal of the evil witch.

In pop culture today, there are two types of witches: the “good” witch and the “bad” witch. The classic dichotomy between good and bad witches directly ties with our conceptions of the visualization of good and evil, which are rooted in racism, ableism, anti-semitism and homophobia. A good witch often looks like a Disney princess: she is usually blonde, white, sparkly, and happy. A bad witch is the opposite: she is usually dark haired, green-skinned, big-nosed, and conniving. The brow that sits upon her wart-filled, wrinkly face is always furrowed as she plots with malintent. In this view, you can tell who is a good or bad person just by looking at them. While these stereotypes are used to quickly identify people in the media, it is dangerous when taken as truth. When we look at Cruikshank’s “Plate 10: Witches Frolic,” we see a perfect example of the evil people via the bad witch stereotype.

In PHIL 200: Philosophy and Witchcraft, we question why the witch hunts happened in Medieval Europe and, of course, Salem, MA. However, the literature does not suggest that those accused of witchcraft between the 15th and 18th centuries wore pointed hats, cloaks and had feline sidekicks: in most cases they looked like everyone else. The classic visual representation of a witch today is the same as depicted by Cruikshank in 1830. There are certain phenotypes that are coded morally, but where did these beliefs come from? Where did the witch costume come from, and why do we collectively associate certain iconography of costumes with witches? While we may never know, for now, let’s just enjoy dressing up as Glinda the Good and Sabrina the Teenage Witch on the spookiest night of the year.

Satan’s Workshop

by Aiko Miller, Gretchen Willmuth, &d Marysabel Morales

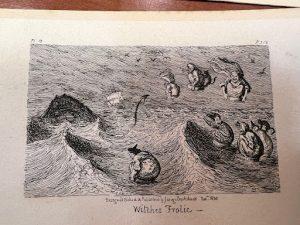

While Santa and his workshop were working all year round to bring gifts and joy to children, Satan and his workshop were busy spreading evil and mischief. In the etching, “Elfin Arrow Manufactory,” George Cruikshank puts a dark spin on the familiarity of a workshop environment. As the caption describes, Satan is depicted slouching over a candle-lit desk in concentration as he finishes an arrow. Elves march in assembly lines assisting Satan in making his arrows. Witches, black cats, bats, and an owl are also present. Cruikshank portrays his interpretations of witchcraft and evil through easily understandable iconography that his viewers will recognize. By bringing his ideas to life in the metaphor of a workshop, and attributing stereotypically Jewish characteristics to the evil beings present, Cruikshank is attempting to convince his viewers of the relationship between evil, witchcraft, and Judaism.

Cruikshank used a setting that was familiar to his 17th century audience in order to convey his interpretations of the way Satan used a workshop-like space in a cave to portray an “Elfin arrow Manufactory.” The etching portrays Satan hunched over a work desk with his faithful elf workers delivering the necessary materials to make the tools with which to produce acts of evil. In the corner of the workshop, a group of Witches and pointed hats stand and gossip. By using the pictorial metaphor of a workshop, which were familiar spaces to most at the time, Cruikshank makes his ideas easily accessible to his viewers. He emphasizes who is part of the construction of evil by including them in his art, in this case Satan, elves, and witches all work together. Thus, without having to read any words, the viewer can interpret the art and understand how Satan constructs his tools of evil.

In this etching, we can also see the connection between witches, evil, and anti-semitism. One clear connection Cruikshank makes between witches and Jews are the pointed hats that the witches are wearing in the etching. The pointed hat that witches wear was likely based on a Judenhut, which is a pointed hat that Jews wore in Medieval Europe. At the time, Jews were often associated with black magic and devil worship, so the common imagery of witches wearing hats similar to that of the Judenhut furthers this connection. Another pictorial metaphor that connect with anti-semitism is Satan pictures with his overexaggerated nose and his horns. There was a notion at the time that Jews had horns, therefore connecting them with the devil since the devil is often depicted having horns. The artist’s use of a large nose on the devil is a classic stereotype of Jewish features, again showing Cruikshank’s connection between Jews, evil, and specifically the devil in this case.

Cruikshank’s easily understandable landscape etch gives the viewer ideas about the way in which Satan conducts his work, as well as ties stereotypical Jewish qualities to evil-beings. By creating an accessible metaphor in his work, Cruikshank’s interpretations are easily understood by the viewers. His interpretations perpetuate dangerous and harmful views that we can see are still in use today. This is one of the earliest pieces of evidence that we have that connects Satan to familiar locations and familiar people at the time in order to further legitimize the witch trials and the villainization of certain community members.

Spectral Sight: An Insufficient Explanation

by CJ Jin, Emily Zhang, & Maddy Rondestvedt

We all wish that sometimes we didn’t have to take responsibility for our own doings. Wouldn’t it be easier if we could blame a random person for our own issues? Even better, what if you could blame a person you hate for all of your issues, and they would actually be held accountable? Well, if this sounds even slightly enticing to you, we are sure you’ll fit right in in the New England witch scene of the late 1600s; unless you’re a woman, of course.

According to novelist William Godwin in his Lives of the necromancers (1834), figures of authority in 1692 Salem had their own ways of dealing with issues: they appealed to what they called the “spectral sight”. This witchy-sounding ability was exactly what witches feared most as the “spectral sight” accurately identified the witch behind every unfortunate situation that happened. How exactly does “spectral sight” operate, you ask? Well, the mechanism behind such an amazing phenomenon is surprisingly simple. Whenever a misfortune occurred for an individual, the figure of the person that inflicted the evil would miraculously appear in front of the victim, invisible to anyone else. Consequently, the owner of the figure, being accused of witchcraft on the grounds of the “spectral sight” experienced by the accuser, was trialed and often executed. Many innocent lives were lost to such baseless accusations.

Reasons as to why this ridiculous phenomenon happened is unclear. However, Godwin, in an attempt to explain the witch hunts, offers an interesting explanation. He writes, “hence the miserable prosecutors gained the power of gratifying the wantonness of their malice, by pretending that they suffered by the hand of one whose name first presented itself, or against whom they bore an ill will.” Those accused, “though unseen by any but the accuser, were immediately taken up, and cast into prison.” Goodwin suggests that those gifted with the ‘spectral sight’ are granted the power of deciding another’s fate. How do they choose? Either by accusing the first name they come across or by accusing those they dislike. And in doing so, they satisfy their own maliciousness. Seems rather nonsensical doesn’t it? Although it is human nature to search for the reasons behind why events such as the Salem Witch Trials occurred, an explanation such as this feels insufficient.

The reason behind this phenomenon isn’t just because the prosecutors were miserable and wanted to execute malicious deeds. At the time, society was highly patriarchal and misogynistic; women were often thought of as secondary or inferior creatures. So, in the face of the unknown, when people wanted answers and something concrete to explain the unusual or supernatural, they pointed toward the susceptible population as scapegoats. Those that had “spectral sight” likely targeted women, who often had no control over the situation. To the prosecutors and the elite, such immoral actions were rational in their mind; they were a product of the social and cultural norms of the time. Analyzing the possible reasons for witch-hunts reveals the disturbing reality of a patriarchal society and the flaws of human nature.

As we transition out of the Halloween season, we could reflect more about its history. Surely, dressing up as a witch deserves a second thought.

What Makes a Witch?

by Campbell Lund, Zipporah Cohen, & Diana Salinas

When dealing with powers ranging from invisibility to animal familiars, identifying the source of these magical abilities might seem like a daunting task. But no need to worry, accusing a witch is actually a lot easier than it seems and evidence will certainly present itself if you look hard enough. Neighbors and even family members accused each other as heretics for any casual misfortune that came their way. Evidence for claims of witchcraft could be as simple as the death of your cow, a sudden cough, or dying crops. These accusations might seem flimsy to the modern interpreter, but it’s important to acknowledge how society’s severity of religious faith made witchcraft an undeniable truth.

This was the reality throughout Europe when the Malleus Maleficarum, a standard handbook on the detection of witchcraft, was published in 1468 and carried into the 18th century. Although evidence for witchcraft has continually presented itself in a case-by-case manner throughout history, we do see a shift when analyzing texts such as Joseph Glanvill’s Saducismus Triumphatus (Full and Plain Evidence Concerning Witches and Apparitions), published in 1726, to a more logical and methodical attempt to not just accept witchcraft as true, but prove it.

The Malleus Maleficarum is the work of two 15th century inquisitors, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. In presenting witchcraft to the public, they tackled everything from the details of performing magic to why witches are usually feeble women with otherworldly libidos. Kramer and Sprenger were able to run wild with their beliefs because witchcraft was taken as a given. At the time, there was no “not believing in God.” It was His way or the highway (and by highway, we mean witchcraft). Because God’s word was the basis of belief, they repeatedly invoke Scripture as evidence for their claims. When all else failed, commonly held beliefs were defended by biased analyses of observations.

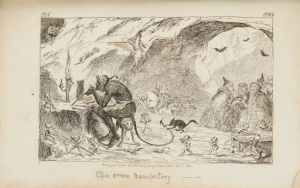

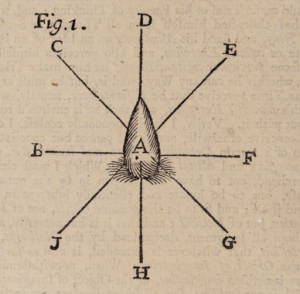

The Saducismus Triumphatus seems to follow the Malleus’ footsteps in trying to prove the existence of witches and other supernatural phenomena by taking a more scientific approach. It begins by confidently explaining the nature of a spirit that would, in turn, make witchcraft a plausible and real practice. By this time, it was no longer sufficient to have God give explanation for the existence of witchcraft; the innate human need for a logical explanation of these events became urgent. Take a look at some of its funky diagrams. It might be hard to believe but Figure 1 represents the “Sensorium of the soul” (whatever that means) while the cube attempts to explain how spirits penetrate matter.

Both Kremer and Sprenger’s and Glanvill’s texts are built upon the same foundation and serve similar purposes: to educate the common reader on the reality of witchcraft. The authors wrote with the goal of conveying the undeniable truth that is witchcraft, though the standards for sufficient evidence evolved. Where Kremer and Sprenger were able to explain away skepticism with religious belief, Glanvill took sought explanations by employing scientific methods. Although today we might read these texts with disbelief, it’s no doubt that they had devastating real-life consequences.

The Domestic Witch

by Chloe Shilale, Alex Asack, & Danya Gao

Despite their recent resurgence as a popular figure in media and Halloween costumes, witches have historically had a negative, fearful connotation. When people think of the witch hunts, they usually think about how many people were killed for being “witches” and tend to assume everyone had a negative opinion of witchcraft. However, Miscellanies by John Aubrey, published in 1696, opposes this notion in its blatant support of magic. The book details information on dreams, omens, and even transportation by an invisible power. One of its most interesting passages is a chapter on magic itself and how to perform it. Each spell is described in detail, and many include a note about who explained the spell to the author, such as a “gentleman of great quality” (107) or an “experienced midwife” (109). The spells detailed in the book vary in both instruction and purpose, including spells to cure a toothache, staunch bleeding, and induce a dream that will reveal your future spouse to you. For example, one spell describing how to cure an ague involves writing the word “ABRACADABRA” on a piece of parchment in the shape of a triangle by decreasing the word by one letter per line, and then wearing that piece of parchment around your neck (106).

This book aims to offer context for the notion of witchcraft, but also offers specific accounts of spells that are more instructional than educational. Especially in the 17th century, witchcraft was feared and considered a dark art. The victims of the witchcraft trials were often accused of interfering with fertility and killing infants and children, but the spells detailed within Miscellanies are softer and even beneficial instead of harmful. After Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger published their witchcraft treatise Malleus Maleficarum in 1487, witchcraft began to take on its modern associations with the Devil. Malleus Maleficarum, translated as The Hammer of the Witches, essentially acted as a guide for hunting witches, whom Kramer and Sprenger identified as predominantly female. This treatise was published a full 200 years before Miscellanies, so even before we opened it, we fully expected to read another book condemning witchcraft and were surprised to see that, if anything, Miscellanies was the opposite.

It’s also interesting to note the context behind the words. This copy of Miscellanies, from the late 17th century, is bound by sheepskin with covers so often perused that they have fallen off. One might consider, then, the reasons that people might have read this book. Was it as an instructional guide, in case they themselves wanted to practice witchcraft (specifically, its domestic applications)? Or maybe to familiarize themselves with the craft, perhaps to better and more accurately accuse others of it? Or was it just used as a humorous escape, just a book of impossible stories about impossible magic? To support this last thought, there’s a faded, scribbled inscription under the previously discussed “ABRACADABRA” section, that notes: “Can mankind ever be so credulous?” (106). While it’s impossible to know if the owner was hoping that others would believe these spells, or casting their own doubt upon the cures that Aubrey describes, it’s worthwhile to consider the reasons why one might not only purchase this book, but also refer to it so often that it eventually falls apart.

“Fear Vicious Men”: Exhuming the Salem Witch Trials with Maureen Cummins’ Salem Lessons

by Yilia Qu, Tiffany Chu, Gabby Szatkowski, & Abigail Chen

From the name of Sabrina the Teenage Witch’s cat to the city’s role as the setting of movies like Hubie Halloween (2020) and Hocus Pocus (1993), it certainly seems that pop culture does not find three centuries “too soon” to comedize the US’s most notorious historical witch hunt. Salem’s depiction in pop culture occupies a wide spectrum, all rooted in the history and infamy of the witch trials. Salem Lessons (2010) takes a different approach, more similar to Arthur Miller’s Tony Award winning 1953 play The Crucible than to the light-hearted mischief of its contemporaries. In Maureen Cummins’s artist book, the accused and accusers are brought to the forefront in first-person perspective poems penned by the poet Nicole Cooley.

Let’s take a step back. Besides the witch trials and Sabrina’s coy cat, what do we know about Salem? Here’s a quick refresher. The Salem Witch Trials were a series of witchcraft cases brought before local magistrates in the settlement of Salem, a part of the Massachusetts Bay colony. February 1692 marked the beginning of the trials, and with it the beginning of an era of mass hysteria and scapegoating. Its origins can be traced back to when the afflicted girls accused the first three victims—Tituba, Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborne, whose poetic stories are all featured in the artist’s book—of witchcraft. Over a year, more than 200 people were accused of practicing witchcraft, and 20 were killed. May 1963, when the remaining victims were released from jail, marked the end of the witch trials.

Salem Lessons gives us a new perspective on the way in which we uncover truths about the past. Beginning with the art book’s slate covering evoking a gravestone, Maureen Cummins reminds us of the weight that these accounts carry. As we traverse through the text, we carry with us the heaviness of the events in the conscious efforts we make to expose and recover the pages. Cummins shows attention to detail in the formatting choices, including her choices of color, text, and material. Names are written in blood-red, and readers have to consciously and carefully open up each page in order to reveal the confessional-toned poetry underneath. We find ourselves perceiving the text in a manner like that of a memorial, paying tribute to those involved one by one.

Growing up, we accepted that lessons learned in school and textbooks are objective, valuable, and true. But Salem Lessons reminds us to stay critical. Not only is the whole book an example of ignored history, but it also points out the biases in knowledge. For example, the poem “The Reverend, Samuel Parris,” inspired by Salem’s extremist prosecutor, indicates that the seemingly good lessons might contain biases and lead to negative consequences. So the sad news is, every piece of information we receive is inevitably fragmented and mediated. In this case, maybe we need to ask ourselves: what is the truth? (If it exists. Does it?)

Lake Waban, Jennifer’s Body, and the Misogynistic Origins of Witchcraft Stories

by Tekla Carlen, Anissa Mansour, and Jessica Wu

In 2021, incoming Wellesley students participate in the yearly Lake Jump tradition. Most of us swim and toss pennies into Lake Waban hoping to somehow find them again come graduation.

In 1624, when Thomas Heywoode wrote Tunaikeion: Or, Nine Bookes of Various History Concerninge Women, women suspected of witchcraft would be thrown into dangerous waters because it was believed witches could not sink or drown. Either way this was a death sentence: if you float, you are a witch; if you do not, you are innocent but also dead.

If witches are powerful beings, how could they let themselves be caught?

This conundrum surfaces when we look at the implications of claims surrounding witches. Logic does not necessarily follow in these accusations of witchcraft, but it did not need to. Here are some things we know about witches’ capabilities. Witchcraft was offensive magic, not defensive. Witches who were jailed could ask to see the judge before their arraignment in an attempt to avoid severe punishment. Their success depended on how “skilled” they were. Could it have just been seduction rather than witchcraft? Was seduction seen as witchcraft? These are questions we can only ponder.

What needs to be understood is the context in which we get these “rules” and “guides” of witchcraft. Manuals to catch witches were written by men with motives to villainize women.

In Philosophy and Witchcraft, we read Malleus Maleficarum [the Hammer of Witches], written by Heinrich Kramer, an infamously misogynistic theologian. He argues that witchcraft is mainly practiced by women because women are intellectually and morally inferior; and therefore easily seduced by the devil.

Kramer is not alone in thinking that women succumb to devil’s seduction easily. We see strikingly similar ideas in Heywoode’s writing; theft is men’s evil and witchcraft is women’s. Both authors characterize women as feeble, malleable creatures who practice magic that harms those around them.

Heywoode provides examples of notorious women he considers to be witches, drawing many from Classical mythology. For example, Circe is one of the first witches he mentions. He says that she “changed men into seuerall shapes of beasts” and set a precedent for many who came after her.

While modern readers would consider this pseudohistory, Circe was a symbol of predatory womanhood in Heywoode’s time. The anxiety men felt about women’s power—even though allegedly, their fault was their weakness—was intense enough that they felt the need to write thick volumes about women deriving power from the devil.

Today, we see similar archetypes in pop culture. The 2009 film Jennifer’s Body, a cult classic, features Megan Fox as a teenager possessed by a demon who eats men to maintain her supernatural strength. Though Jennifer is not a witch, her threatening sexuality is also represented as a paranormal power that targets men, and an iconic scene shows her swimming in a lake in a way that highlights both her femininity and her otherworldliness. It may not be Lake Waban or medieval “moates and riuers,” but some ideas never change.

A Peek Into Witchcraft Beliefs in 1622

by Amelie Chen, Hannah Stickler, & Gabrielle Li

Among the many books in Wellesley’s Special Collections is “L’incredulité et mesreance du sortiledge plainement conuainecue”, a 1622 book that discusses the existence and validity of witchcraft and magic spells. While the nature of the book renders it a difficult read (written in old French), its table of contents, the only image in the book (Fig.1), and a poem attached to the image may help us gain some insights into what the author is trying to express.

The author, Pierre de Lancre, dedicates the beginning of his book to a discussion on the existence of witchcraft. As shown in the table of contents (Fig.2), he then talks about several topics including fascinating, fondling, scopism, divination, magical ligation and apparitions for half of the book. Though it seems that the author tries his best to be objective and neutral by examining as many aspects of the matter as possible, his presentation of the history and arrests of a number of infamous witches in the second half of the book gives his personal belief away. It is unlikely that a truly impartial author would go through cases of notable witches in such an extensive, meticulous, and sensationalized way, which possibly sways his readers into accepting the existence of witches and malicious supernatural power. Therefore, it’s probable that the author is predisposed to the belief that witchcraft does exist and he tries to convey the idea to his readers in this book, despite his effort to sound unbiased.

Alongside the table of contents the author includes an engraved image of witches amidst ritual with a caption in the form of a poem titled “Abomination of Sorcerers” (translated from old French). This image characterizes witches as deviants who use their sexual power to entice men into enchantment. The author, a white, male, Christian, used this image to display the “worst characteristics” of females in an attempt to demonize them. Using this image as a guide, the reader learns that women (especially the presumptuous or elderly) desire to enchant, deceive, or otherwise harm targeted groups such as men and children. The image also illustrates how witches have particularly close relationships with animals, and may use certain tools to aid their magic such as broom sticks, potions, or other spells. Any of these characteristics and tools may be used as identifiers for witches in the 17th century.

Attached below the illustration is the poem, “Abomination of Sorcerers”, which directly condemns the ritual happening in the picture. In the text, witches are referred to as servants of the devil who apply evil magical spells that stir up hatred and horror on the enchanted commoners. The third stanza narrates the witches’ ritual of torturing people and causing chaos through fire that burns eternally. Such a description fits with the engraved image: on the top right corner of the illustration, through the tiny window, we can see exactly what is being described in the poem! This text, compared to the related image, is a more direct way in which the author could express his emotion towards witchcraft — his indignation and disgust seem to be jumping off the page! While the illustration serves as a visual representation, the poem gives the audience a vivid imagery of what a witch is like.

The book “L’incredulité et mesreance du sortiledge plainement conuainecue” has left a strong impression on us in that while we are unable to fully comprehend the author’s complete arguments (since we didn’t read the whole book), we can see his dispositions and beliefs on the matter of witchcraft through the image and poem he chooses to put at the beginning of the book. By portraying and condemning a stereotypical witch and her evil practices through a vivid image and evocative poem, the author, although expressing his unbiasedness in the table of contents, validates the existence of witchcraft and the diabolical rituals associated with it.