“My heart thudded in a black plastic bag, its heartbeat gradually snuffed out as North Carolina turned red, then Georgia, and finally Pennsylvania,” wrote a close friend from Beijing, currently a first-year at Medill. The fate of international students hinges upon the chosen presidential candidate, while they themselves are powerless, without the right to vote. Otherwise integrated into classrooms and clubs, the elections reveal the chilling notion that 1 out of every 8 students around us have little say in the country they live and study in. In the face of another four years under a nativist head of state, international students can only brace themselves and strategize for self-preservation.

Despite growing up under completely different educational systems, students around the world compete for a spot in elite American colleges as a means of accessing higher-quality education and socioeconomic mobility. Many students aspire to work in the US after graduation, as it is the forefront in many fields, not to mention higher salaries. For students from countries like China and Russia, staying in the US also means enjoying various freedoms of expression, which in their home country are privileges, not rights.

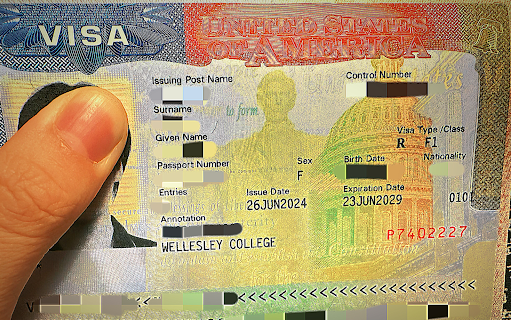

Working after graduation usually hinges upon the H1B visa, which is obtained via lottery. Luckily, international students have a bit of time. After graduation, F-1 visa students are granted one year of “optional practical training,” or OPT, which requires working full-time in an area directly related to their area of study. STEM students (which, at Wellesley, luckily includes Economics) can apply for a 24-month extension, effectively giving them three chances in the visa lottery. Historically, the number of visas granted is capped at 65,000 (with an additional 20,000 for graduate students) per year, with the odds oscillating between 25% and 40%.

With a Donald Trump presidency term, this predictability is a lost luxury. Looking back to his first term, the “Buy American and Hire American” executive order triggered H1B denial rates to surge from 13% in 2017 to 24% in 2018. To international students, denial means they must leave the US within 60 days, regardless of whether they can find a job elsewhere with similar pay and required skill sets. The real fear lies in the policies that could potentially be passed this term. In 2015, Ted Cruz (R-TX) and Jeff Sessions (R-AL) proposed a bill that entirely eliminated the OPT and required a minimum salary of $110,000, which fortunately has been abandoned after the 2016 elections. Trump recently appointed Kristi Noem to lead the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees the US Citizenship and Immigration Services. Noem, who was an opponent of COVID-19 safety measures and denies climate change, doesn’t seem too friendly towards international students, as evidenced by her firm adherence to the MAGA movement.

Alternatively, some students secure jobs that provide visa sponsorship, where the employer provides documentation that justifies why hiring an immigrant worker is necessary. However, these positions tend to be highly competitive seats in large multinational companies, concentrated in software and finance. In anticipation of tightening H1B approvals, international students must either secure a sponsored job, or at least declare a STEM major to buy two years of time. Finding a third country — such as the U.K. — is an alternative for those who are determined not to return to their home country. Considering that liberal arts colleges have limited recognition as prestigious institutions outside of the US, the Wellesley degree loses much of its power. In the end, college is no longer a safe space to explore, but a four-year grace period before the F-1 bomb explodes.

After the election, I was enraged, betrayed by the land of opportunity that I had entrusted my future to. Anger sizzled into bitterness and finally, disillusionment. As a non-immigrant, the country had almost zero obligations towards me, even less than that towards refugees. Realizing I had gambled my parents’ hard-earned money for my own future, I settled upon a politely suppressed fear.

While the election conversation at Wellesley focuses on abortion, the loss of trans rights, and protection of the families of undocumented immigrants, one in eight students face the uncertain future of their ability to live and work in the US post graduation. Fully paying and often well-dressed, international students can seem like a rather privileged group, almost undeserving of occupying the post-election discourse, but they certainly face a kind of existential threat. With limited knowledge of partisan forces and no affiliation to particular states, it can be hard for international students to participate in election conversations in the first place. Appreciative of the good intentions of the Community for Political Engagement (CPE) and Slater International Center, I skipped the self-care conversations. Tucking my coloring books and half-finished scarf into the bottom drawer, I turned to LinkedIn, determined to outsmart the man who called my family carriers of the “kung flu.”

Contact the editor(s) responsible for this story: Caitlin Donovan