The spread of information regarding the Ebola epidemic has induced frenzy across America over the past couple of months. There have been several cases in New York and New Jersey where those thought to have had the disease have been quarantined, either in a hospital or in their home, for days until they were deemed to be in good health. Last week, Kaci Hickox of Maine was quarantined in New Jersey even though she presented no symptoms related to Ebola and later tested negative for the disease.

She has fought to have the quarantine lifted but is still mandated by the state to remain under monitored until Nov. 10. On the other hand, President Barack Obama recently hugged Nina Pham (the first person quarantined in the United States) post-recovery, arguably illustrating the need to remain fearless and unbiased when dealing with victims.

These cases illustrate how we are trying to take all necessary precautions to prevent the spread of the disease, but the handling of victims can lead to ostracization and the tendency to overlook the rights of the individuals if done so improperly.

While I understand that the concern has been put into motion in terms of state regulations and laws in order to prevent the spread of the disease, I agree with Obama when he says that state-mandated actions undermine an individual’s ability to make decisions regarding her own health.

In the Hickox case, we can see the problems that are induced when the state treats the body as infected until proven healthy, and consequently treats that presumably infected body as a vessel for disease instead of a vessel for the life that belongs to the individual.

It is also as if the state is saying that they know more about how to take care of an individual’s body than the individual herself, and that is a direct interference with the notion of human rights.

I believe an apology is in order for Hickox, as while the quarantine had preventative intentions, it disrupted Hickox’s individual life and should have been at minimum reduced to direct contact monitoring immediately after her test for the disease turned out to be negative.

Furthermore, some have wrongfully compared the epidemical experience of Ebola to the AIDS pandemic years ago, saying that in dealing with Ebola, we must be cautious not to induce stigmatization or cause a similar backlash as we did with AIDS.

However, the two represent entirely different concerns for public health and come with stigmas whether we will them to or not. The AIDS virus came with a strong stigma related to homosexual behavior, irresponsible drug use and other presumptions that blamed the victim for the contraction of the virus.

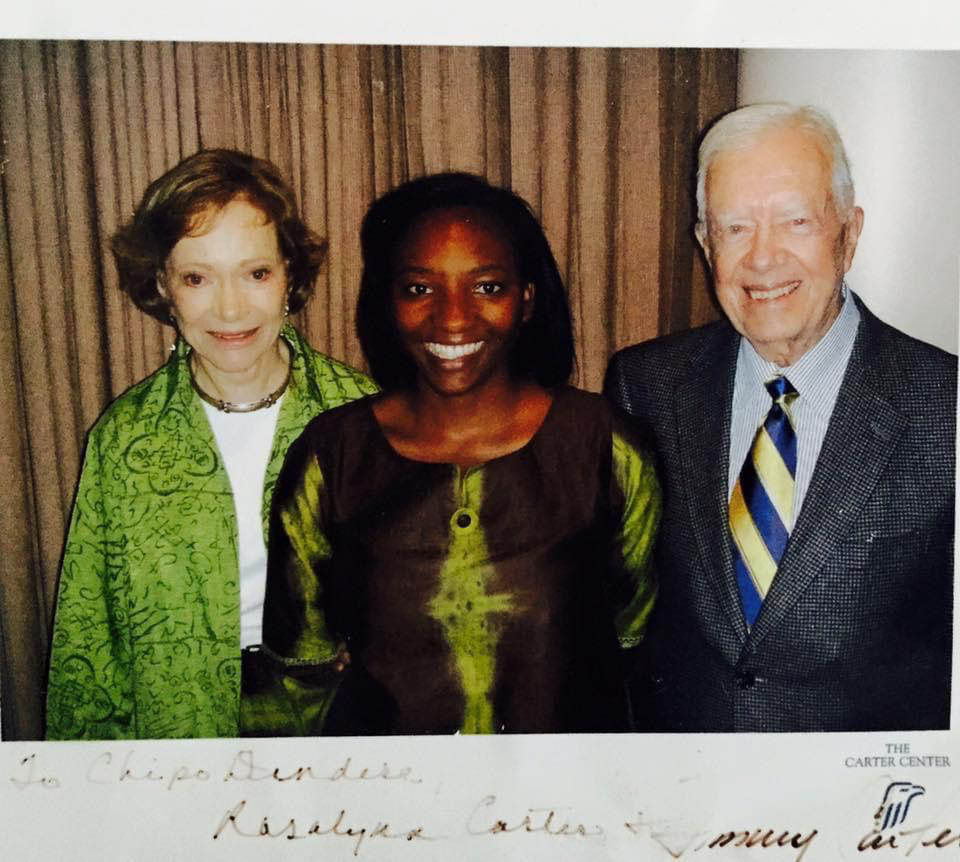

However, the Ebola disease is coming with a strong stigma related to cultural differences and the presumably indigenous, unhealthy African body. This stigmatization instead places blame on the place of origin and associates it with being part of a dysfunctional race.

While the concern regarding ostracization of the U.S. victims of Ebola is valid, it could never be the same as that of AIDS victims. This is not to say that the cultural stigma associated with Ebola is not troublesome. It represents a huge problem regarding the acknowledgment and acceptance of cultures other than our own.

But while we might be afraid of the spread of Ebola, the fear surrounding AIDS involved much more than just an infection. In this way, the two are virtually incomparable.

Regardless, both circumstances may have been less detrimental if people had been more educated in terms of what actually occurs when the body is infected. Increased awareness about the way Ebola affects the body and other research will help us to handle this far better than we handled AIDS.

When considering the issue here at home, we as Wellesley students must work against the cultural stigmatization and hopefully inspire others to recognize that Ebola is a disease, not a reflection of a race.