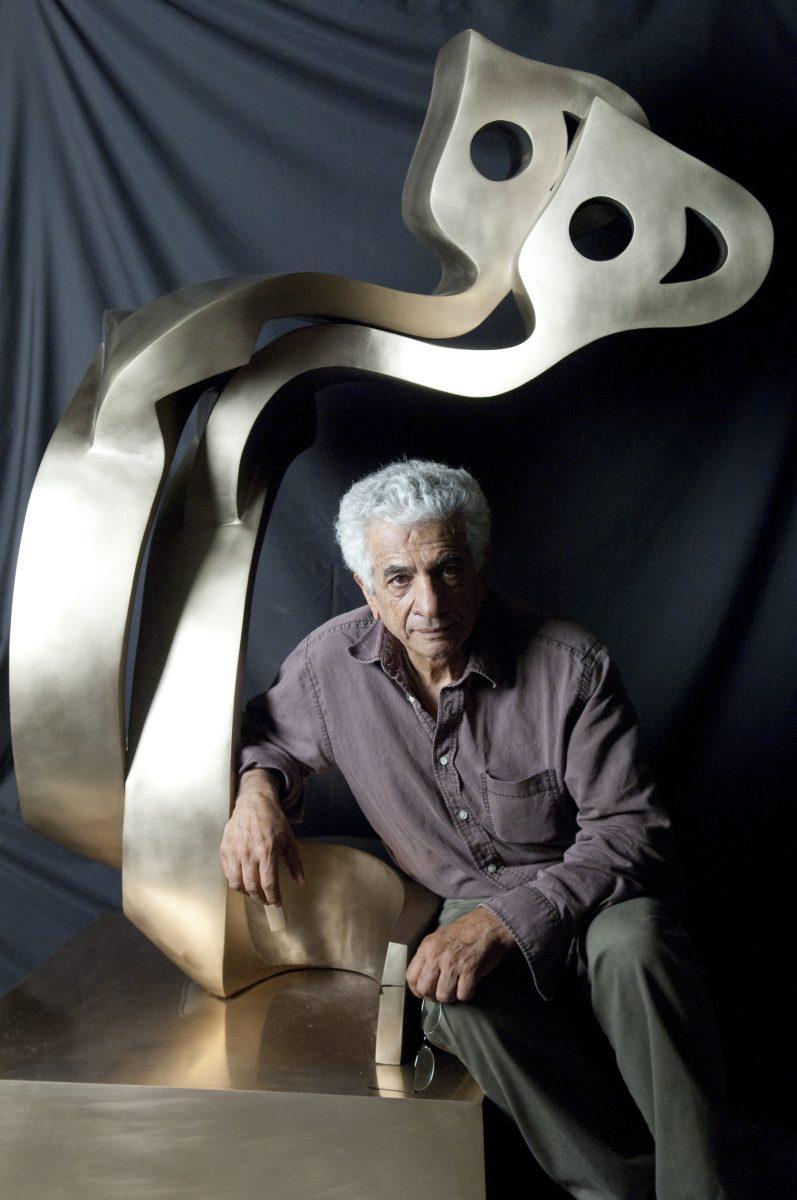

Despite record-breaking snowfall, Collins Cinema was bustling with students, faculty and community members for the Davis Museum’s Spring Opening Celebration. The highlight of the museum’s spring semester is the first ever U.S. museum retrospective of Iranian sculptor Parviz Tanavoli’s work. In fact, there hasn’t been an exhibition of Tanavoli’s work in the United States since 1976, although Tanavoli is often referred to as the father of modern Iranian sculpture and is a founding member of the Saqqakhana movement.

At the opening celebration, Tanavoli participated in a roundtable discussion with the co-curators of the exhibit: Lisa Fischman, the Ruth Gordon Shapiro ’37 director of the Davis Museum and Dr. Shiva Balaghi of Brown University.

The exhibit represents almost all the media in which Tanavoli works. Although Tanavoli is best known for his modern and expressive sculptures, he has also created works in paint, printmaking, jewelry, rugs and ceramics. The exhibition opening at the Davis will be comprehensive in terms of media, with one notable exception.

Due to U.S. sanctions on importing Persian rugs, Tanavoli’s textile art could not be displayed at the Davis Museum for the retrospective.

The loss of Tanavoli’s textile art from the exhibition is an important blow given his extensive writing on Persian textiles. In addition to other books about art collecting and Persian tradition, Tanavoli has authored several books on various kinds of textiles, ranging from flatweaves to traditional Persian lion motif rugs.

The idea for the exhibition at Wellesley was born when the co-curators saw his art treated badly in Tehran. Although Tanavoli’s art commands a high value on the market, the curators felt that it was being mishandled. When Wellesley College trustee Maryam Homayoun-Eisler heard about the situation, she recommended setting up an exhibition of Tanavoli’s art at Wellesley.

Because the exhibit at the Davis features such a broad range of Tanavoli’s work, it offers an excellent chance to study the progression of one particular motif: “heech,” the Farsi word for nothing or nothingness. His project exploring the meaning of “heech” has spanned 50 years as of 2015, with its origins in 1965. During that time, Tanavoli has recreated “heech” in various media, including jewelry, ceramics and neon.

At the roundtable, Tanavoli discussed the role of heech in both Persian tradition and pop culture. Tanavoli emphasized that artwork’s value is largely in its sociopolitical context as well as in its aesthetic content, which drove him to explore the meaning and significance of “heech” and other Persian motifs. Wellesley students expressed interest and enthusiasm for Tanavoli’s incorporation of Farsi characters into his work. “I’m a big fan of Iranian art and I’m a Hindi and Urdu student, and a lot of his art uses scripts, which I love,” said Maureen McCord ’18.

Heech is not the only Persian symbol that Tanavoli has investigated. Tanavoli’s art often draws from the intersections of Persian history and modernity. He mentioned at the roundtable that he was also inspired by the Persian love story of Farhad and Shirin.

The story that tells the tale of Farhad, a commoner who falls in love Shirin, a princess. Both meet a tragic ending that has become as well-known in Persian tradition as “Romeo and Juliet” has in the West. “Farhad became like my ancestor,” Tanavoli said, describing his heartfelt connection to Persian lore.

Another traditional motif Tanavoli considers in his work is the Persian lion – Tanavoli saw a lion rug in Shiraz and was inspired to work with the motif. He wrote a book about the presence of lions in Persian textiles that, as he told the roundtable, he kept himself busy with during the Iranian Revolution.

Balaghi reiterated that no other university or college students, even in the Middle East, would have this level of access to Tanavoli’s art. Other than the internet, the only other place to for an American to see artwork by Tanavoli is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, which purchased Tanavoli’s sculpture “Poet Turning into Heech” in 2012.

Tanavoli’s work is notable not just for its artistic prowess, but for the attention that it has commanded from collectors. His art has set record prices in Dubai, in the U.A.E, and at Christie’s auction house. The high profile of the exhibition drew reporters and photographers to the Davis opening.

Although the Davis is a small museum, global media has reported on the Tanavoli exhibition. The Guardian, based in the United Kingdom, published a piece on the exhibition, and Hali Magazine, an internationally known art magazine, named it an Editor’s Choice exhibition.

The retrospective of Tanavoli’s work is also an important piece in a larger shift of arts culture at Wellesley. This semester, in addition to Tanavoli’s retrospective at the Davis, Collins Cinema will be showing a film series called “Women in Iranian Cinema.” This will complement a symposium called “Art and Reality: Contemporary Middle Eastern Art in Context.”

Although the study of art history at Wellesley typically conjures up images of European Renaissance paintings, in the vein of “Mona Lisa Smile,” Wellesley students, however, seem eager to embrace the change.

“I just know about classic, medieval art, so Iranian art is something I haven’t seen, and I’m looking forward to fighting my Eurocentrism,” Sarah Michelson ’18 said.

This year’s Spring Opening celebration marks the opening of three new exhibitions, “Parviz Tanavoli,” “Michael Craig Martin: Reconstructing Seurat,” and “Rembrandt and the Landscape Tradition,” all of which are open at The Davis from Feb. 10, 2015 to June 7, 2015.

Photo Courtesy Of Parviz Tanavoli.