This past summer, I volunteered at a hospital, located near the Syrian border. Working with refugee patients, I witnessed the physical and emotional wounds and burdens they carry on a daily basis. After their home country was overrun by Bashar al-Assad, Syrian rebels and the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the refugees were searching for a safer place to live.

In 2011, during the height of the Arab Spring, Syrian people took to the streets, protesting al-Assad’s presidency (which closely resembled a dictatorship, since he became president in 1971). The Syrian government violently attempted to muzzle these demonstrations by open-firing on the demonstrators, which intensified the rallies and spread a freedom-seeking fever across the country.

2012 brought a temporary pause in violence as rebel fighters seemed to be reaching a stalemate with the government. Then Hezbollah, a Lebanon-based terrorist group, started sending fighters to Syria, effectively helping the Syrian government systematically murder their people. At this point there were just over 2 million Syrian refugees, a dramatic increase by almost 1.8 million persons from the previous year.

On September 14, 2013 an agreement between Syria, Russia and the United States placed all of Syria’s chemical weapons under international regulation and monitoring by the United Nations. However, this momentary promise of hope for peace was interrupted by ISIL. After declaring a caliphate, ISIL began seizing territory in Syria in 2013.

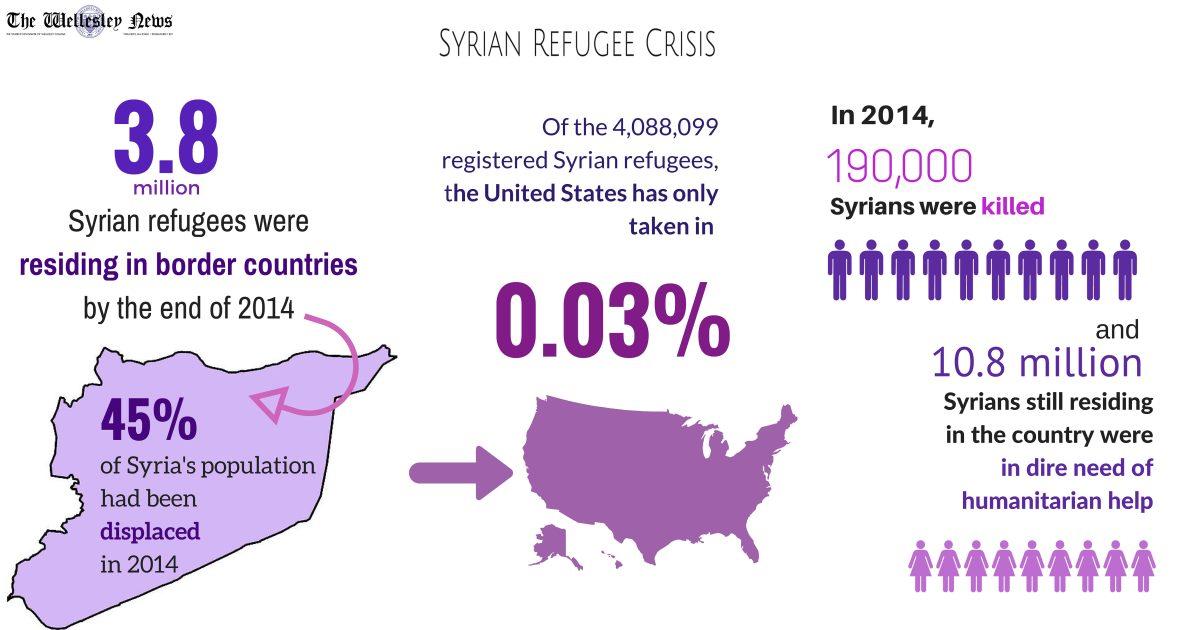

Towards the end of the year 2014 there were 3.8 million refugees from Syria residing in border countries. Amnesty International estimated in 2014 that 190,000 Syrians had been killed and 10.8 million Syrians still residing in the country were in dire need of humanitarian help. 45% of the country’s population had been displaced by this point.

Syrian families, however, are often unable to move, as many countries have refused or have been resistant to providing amnesty for these refugees. Often countries argue that their immigration services are not equipped to handle the massive flux of refugees. Of the 4,088,099 registered Syrian refugees, the United States has only taken in 0.03% — a minute amount. And if refugees are allowed to resettle into a new country, they are often housed in temporary settlements, where public health and education issues are of concern.

Yet, relocation alone will not solve the Syrian refugee crisis. Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, a chemical weapons adviser to NGOs working in Syria and Iraq, argued in a recent opinion piece in AlJazeera that ultimately, the solution to this issue involves “defeating ISIL and removing Assad from power.”

My experience showed me up close the need of the Syrian people and the struggle to win back their country. Though resettling Syrian refugees can be an immediate solution to solving this refugee crisis, I believe that the international powers should think about a more long term solution. In the short term it would be helpful for countries, such as the United States and those in the European Union, to take in more Syrian refugees in, but ultimately this will not end the Syrian crisis. Hopefully a long term solution will involve overthrowing the forces that seek to destroy Syria, such as ISIL and al-Assad, and allowing for the return of the Syrian people to their homeland in peace.

Dr. Necessitor | Oct 11, 2015 at 10:21 pm

What’s more shocking is the refusal of Muslim countries to take in Syrian refugees. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and other extremely wealthy Middle Eastern countries have refused to accept Syrian refugees. America does a piss-poor job of assimilating POC immigrants and Europe is much worse. This is a recipe for disaster in Europe.