Keeping with the Cuban theme of this semester’s Cinephile Sunday series, Collins Cinema hosted a screening of “The Last Match” (“La Partida”, 2013), followed by a lecture on Cuban LGBTQ cinema from special guest David William Foster last Thursday. While I like to consider myself a movie buff, I will readily admit that my knowledge of LGBTQ cinema is limited and that the extent of my knowledge of Cuban cinema prior to this event was just the film “Memorias del Subdesarrollo,” screened in Collins last month as part of the Cinephile Sunday series. But there is no time like the present to learn, and who better to learn from? Foster, who is a Regents’ Professor of Spanish, Humanities, and Women & Gender Studies at Arizona State University, wrote a book on the subject, “Queer Issues in Contemporary Latin American Cinema,” which is available in Clapp and digitally through the LTS website.

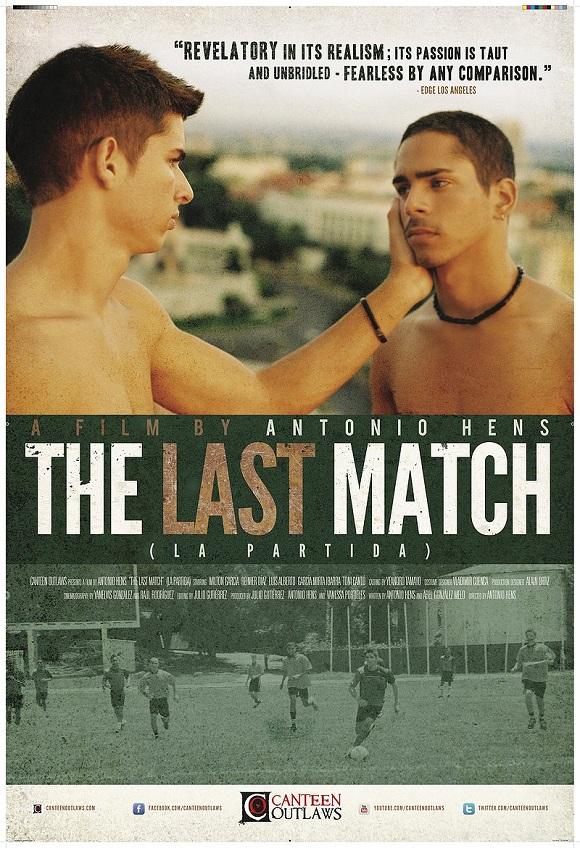

“The Last Match” itself is a respectable example of a modern, low-budget drama, though it falls into two of the traps common to that genre: obvious budget limitations and a sudden, melodramatic ending which Foster himself—though evidently fond of the film— described in his lecture as “pathetic.” The film depicts the relationship between two young amateur soccer players, Yosvani and Reinier (Rei), as it develops from platonic to sexual, and their growing struggle to keep it secret. For the most part, some intriguing subplots, such as Rei’s family’s knowledge and outright endorsement of his prostituting himself to male clients, manage to keep the otherwise stereotypical forbidden love story from becoming truly cliche. All in all, “The Last Match” is an interesting, if not overly memorable, drama about the developing relationship between two young men in modern-day Havana.

Putting “The Last Match” in the larger context of modern Cuban cinema, Foster’s lecture shined a new and fascinating light on the film. He described the film as a study of various forms of hunger, whether that be lust, hunger for food—Foster cited “The Last Match” as the first film he knows of that depicts the food shortages prevalent in modern Cuba—or greed, which also plays a central role in the film.

Foster went on to discuss modern Cuban LGBTQ cinema as a whole, and I couldn’t help but notice some fascinating contrasts with its American counterpart. For example, the 1994 film “Fresa y chocolate,” which Foster described as the “stage-setter” for modern Cuban cinema, was such a phenomenon upon its release in Cuba that people broke cinema doors in their excitement to get in. While fan culture is no less prevalent here, I cannot think of an example of a film that has inspired that much public excitement in America that also prominently features a non-heterosexual couple.

This, of course, does not mean that Cuban cinema is more inclusive of the LGBTQ community than American cinema, though Foster did describe it as a growing genre. For example, the question of lesbian visibility in Cuban cinema asked during the Q&A portion of the event received the shortest answer of the night: an immediate and decisive “no.” Foster later elaborated and bluntly stated that “the representation of women is appalling in all of these films.”

But, more than anything, Foster’s lecture highlighted just how much you can learn about a country by looking at the films it produces. Although Foster’s visit is over, there are still two films left in the Cinephile Sunday series: “La vida es silbar” (“Life is to Whistle”), Nov. 8 at 3 p.m. with an encore screening Nov. 12 at 5:30 p.m., and “Viva Cuba”, Dec. 6 at 3 p.m.