Friendships serve as relationships away from relationships: a romance or a marriage trouble us with cumbersome sexual expectations, while family binds us to obligations or kinfolk we may wish to escape. When our romantic or familial relationships break apart, our first instinct is to knock back a few glasses (or bottles) of alcohol with our friends, during which we may either discuss personal issues thoughtfully or blither about something or other, laugh about absolutely nothing. And isn’t that what friends are for? They’re privy to our dirtiest secrets — our most inebriated alter-egos. They arrive packaged with several pints of Ben and Jerry’s, video games, cheesy erotica and a few YouTube videos that only make sense at three in the morning. New studies encourage college students to latch onto their friends, an achievement worthy of a degree in our career-oriented, fast-paced lives. At Wellesley, we’re hounded to create and manage social networks that would secure us a career, but for the sake of our mental well-being and more enriched adulthoods, we should aim for loftier goals and seek friendships that would survive all cracks of adulthood: heinous boss, awkward dates, little pink slips and ugly haircuts.

Investing time and labor into long-term relationships may improve your mental health. A study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B surveyed over 2,000 high school students and found a strong correlation between those who lacked friends with good mental health and depression symptoms. Conversely, the same study found that students who had a large circle of friends were not as likely to be clinically depressed. Another study surveyed around 4,642 Americans aged 25-75 in 1995 and again in 2005, concluded that poor quality of social relationships was a major risk factor in long-term depression. In this context, poor quality entails friends who themselves are struggling with depression and other clinical mental disorders. Such studies suggest that taking the time and effort to form a healthy, platonic relationship with someone, where one is not always emotionally dependent on the other, may prove beneficial in the long run.

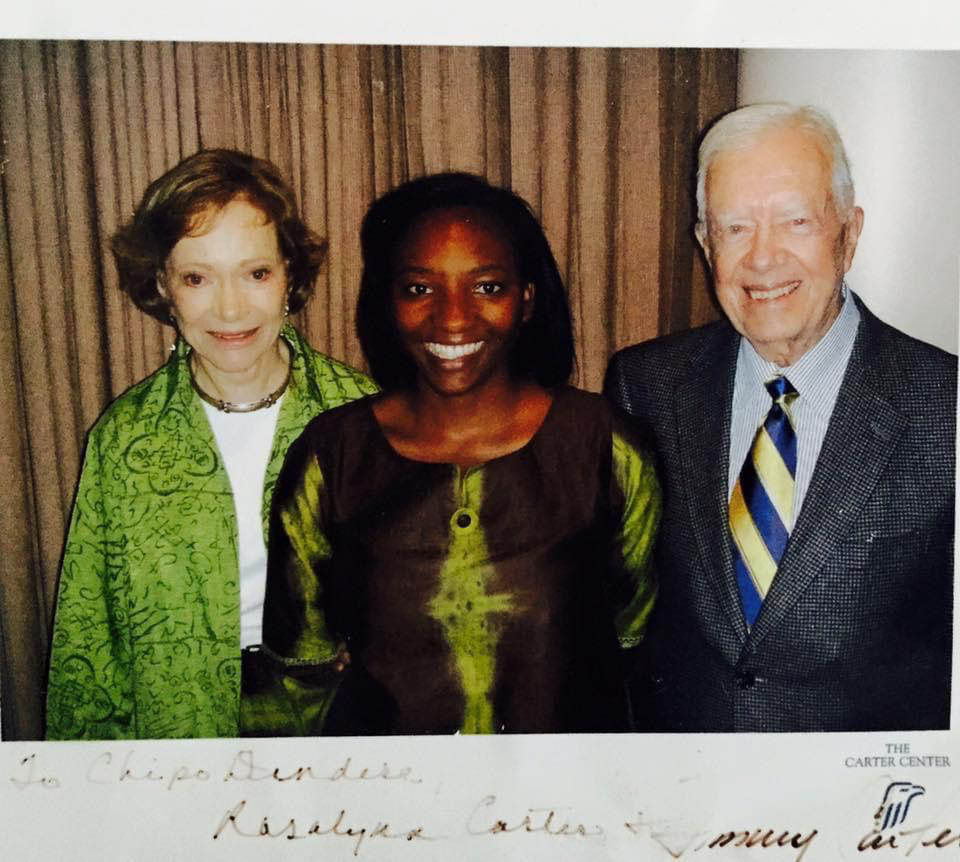

Rarely do we find testaments to enduring friendships, but one example was published as a photo essay in the Atlantic last month. Photographer Karen Marshall began taking photos of a group of teenage girls living on the Upper West Side in 1985 and continued to do so for 30 years. The photos weave together fragments of adolescence and womanhood, from slumber parties to first cigarettes to weddings, and even the tragic death of one of the women in the group. The photos portray a kind of familiar comfort and idleness present in the best of friendships, and demonstrate how the best moments in our lives are when we’re with our friends, playing hopscotch or arguing about which frat boy is cuter.

The conversations are meaningless, but the uninhibited feeling of camaraderie, the taste of damp night air and the scratchiness of your friend’s jacket, endures a lifetime. Even when miles apart, what exists in place of your missing friends is not loneliness, but the knowledge that you remain significant to someone who willingly and by choice cherishes you.

And yet, friendships shatter as easily as they form. I can recall the night a friend and I ran around the campus till the wee hours of the morning, swapping candy and learning each other’s entire histories by heart. The weeks afterward ushered in new classes, new classmates, and emails that grew more and more clipped till they stopped altogether. A dinner every day becomes once a week, once a month, until you pass them in the dining hall one day and you vaguely wonder whether you should even say hello. Occasionally, randomly, a thought flits through the muddled mind: Wasn’t there that girl who liked to dip her Snickers in her Coke? She kept a pink stuffed bunny? Her name started with an S?

Several factors can explain the phenomenon of deteriorating friendships in college. First, college students use social media to build extensive networks for contacts and career opportunities, but the process takes time away from building deeper bonds or contacting old friends. A psychological reason may also lie behind the emphasis on networking over friendships. When we contact strangers through Linkedin or Facebook, we are not expecting a response, whereas a cold shoulder from a former best friend hurts us and can make us feel neglected or even worthless.

In addition, social media leaves us little reason to drop our old friends personal messages or leads us to erroneously conclude that we are no longer good enough to stay in touch. How many times have we scrolled through our Facebook feed, swallowing that desperate need to compete with our former classmates’ prestigious internships or hot new boyfriends or girlfriends?

Social media makes us privy to personal lives and accomplishments, but erases the story behind filtered photos of sorority parties and every self-congratulatory tweet. The selective control we have over social media–choosing to inform the world about our college acceptances, but neglecting to mention the nights spent crying over rejections, for example–ironically isolates us from other people. Understandably, many people recoil from sending intimate accounts of their lives to former friends who unwittingly construct an illusion of a perfect, put-together life.

For all the time we spend emphasizing the importance of friendships, a crucial fact remains: forming a friendship necessitates mutual vulnerability, a willingness to let go of our composure and behave as weirdly as we please. The thought of reaching out to someone strikes fear in all of us, but maybe it’s time we send a brief email to those we formerly knew and loved, and rekindle those inside jokes, conversations filled with interrupted sentences and snorts of laughter, and late-night Skype sessions spent talking about absolutely nothing and absolutely everything.

Photo courtesy of Wellesley College