If you asked me if I would like to sit next to a political conservative or a liberal-minded individual at dinner, I would choose the former. The same applies to the classroom; if registration was based solely on a professor’s political leaning, I would be predisposed to choose the conservative. While I draw a line when it comes to actually voting in political electorates, I find a great deal of value, growth and self-challenge from engaging with beliefs that diverge, confront and simply disagree with my own. Perhaps, that is my comfort with discomfort or my naive lack of self-preservation. Regardless of my own political allegiance (liberal, democratic and left-leaning), I reject the assertion outlined by Bruce Sheiman in his recent letter to New York Times editors that conservative opinions are less credible and less valuable in academia. While conservatism in biology is anachronistic, the diversity of political beliefs is crucial in academic settings.

In his letter, Sheiman fails to distinguish political conservatives from traditionalist schools of thought. He argues that conservative views of biology, economics and ethics are unequal to liberal views. Consequently, there are and should be few conservatives in academia. And there are, indeed, fewer. In the journal, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, scholars from six universities noted a “political groupthink” in academia: liberal social psychologists outnumber politically conservative social psychologists fourteen to one. This too is obvious when considering campaign donations by Cornell’s faculty: over 96% of donations to political candidates have funded Democratic campaigns. Arthur C. Brooks of the Times noted this general imbalance as evidence of discrimination and hostility: 79% of social psychologists stated they are less likely to support a conservative hire over a liberal with identical qualifications. Here, Sheiman’s argument is both flawed and justified. Conservative biologists — that is, creationists — are and should be markedly absent in accredited universities; evolution is a fact, whereas creationism is unsubstantiated and ignorant of the scientific method. However, political conservatives should not be absent from the humanities or social sciences.

The definition of conservatives is variant; hereon, I would like to abide by the common Wellesley definition: the political minorities that sit a little too right. While the presence of conservatives is lacking at the College, it’s an important voice. As the authors of the study argue and Brooks highlights, “increased political diversity [improves] social psychological science by reducing the impact of bias mechanisms such as confirmation bias, and by empowering dissenting minorities to improve the quality of the majority’s thinking.”

When the majority rules, widely held ideas do not face the criticism and standard of scrutiny allocated to minority ideas. In science, we can see this as a Nature article that goes unquestioned merely because of the authorship and associated prestige. Clearly, this example is dangerous as it assumes away the hallmark of science: reproducibility. The failure to reproduce results — to contend conclusions made by a group of researchers — is akin to accepting an unsubstantiated argument. Rather, the diversity of research supports steps in the right direction; science gets closer to the truth when contention and doubt supports further investigation, which ultimately increases the number of data points. Diversity reduces the bias of research, and more generally, of academia.

Likewise, in the humanities and social sciences, the diversity of opinion allows for contentious, but productive conversation. Professors play an important role in offering viewpoints. While some argue that emphasizing diversity of political beliefs could take away from general quality, it assumes away the validity of the opposing side. If anything is to be derived from history is that the “right side” isn’t always the “same side.” Groupthink, which is produced from isolating oneself from dissenting viewpoints, may be a purportedly extreme example, but it has insidiously influenced and arguably determined political, military, social and corporate failures — including the 2003 invasion of Iraq after 9/11. In any of the cases, one theme does exist: the majority opinion was assumed to be the right opinion. Unfortunately, this assumption is wrong.

In less dramatic circumstances, if Wellesley is to be culturally, religiously, socioeconomically or in other facets diverse, our community must encourage the presence of contention. Stressing diversity and inclusion must be inclusive of all permutations of diversity. If conservatives or Republicans are underrepresented in academia, it surely isn’t because there aren’t plenty. American politics is red; it is no secret that Republicans hold the reins of both houses of Congress and the greater number of state legislatures and governorship. Even few miles out from the Wellesley Bubble, liberal students can find the right side of the spectrum. While we can try to avoid opinions we do not like, we cannot let those opinions be unrepresented, ignored, devalued or unengaged on campus — whether it is in personal conversation or when hiring professors. Homogeneity has never been an indicator of growth or conducive to intellectual rigor.

Avoiding confrontation is intellectual coddling; we have to engage with different opinions to realize and address the flaws in our own. We learn from disagreement. Even if different opinions are available via social media or out on the streets of Boston, their absence on campus wrongly devalues their importance. I personally have benefitted the most not from conversations with my liberal compatriots, but from heated debates and genuine dialogue with strangers, classmates, professors and friends with whom I wholeheartedly disagree.

Moreover, professorial diversity challenges the comfort of political beliefs and emphasizes the legitimacy of the opposing side. It equips students with the skills to defend, evaluate and develop their own beliefs, opinions and arguments. It provides mentorship and room to grow. Why? Because diversity supports an environment of questioning and investigation, whereas homogeneity is acceptance of the norm. Further, the argument that conservative ideologies are erroneous, and ergo, should not be among academics, assumes that students are incapable of differentiating their own beliefs from those of the professors. It assumes students derive and reproduce professorial ideologies, and are incompetent at developing their own opinions from a buffet of beliefs. And that is a dangerous condescension.

If conservative opinions are considered to be far from your own truth, they are still inherently important because they question comfortable assumptions and instigate investigation. The presence of conservative opinions in all ranks of academia is crucial because it affirms unconditional diversity, supports questioning and allows students to solidify and separate their own beliefs from derived ideologies. Truly, many of my conservative peers seem more convincing in their defenses and assertions. They merely have had the practice of debate or dialogue and do not operate in the same comfort allowed to liberal students — a comfort of political acceptance that does not exist beyond Wellesley. If we value professors not merely on their research or resume, but their ability to challenge students, then a diversity of political ideology should be reflected in academia. The imbalance of ideology — one that surely does not represent America — indicates an environment of close-mindedness. Therefore, if we preach diversity at Wellesley, we must see it in all of its forms. If we detest far right individuals for turning a deaf ear to liberal views, what makes liberals who likewise reciprocate any more academically respectable?

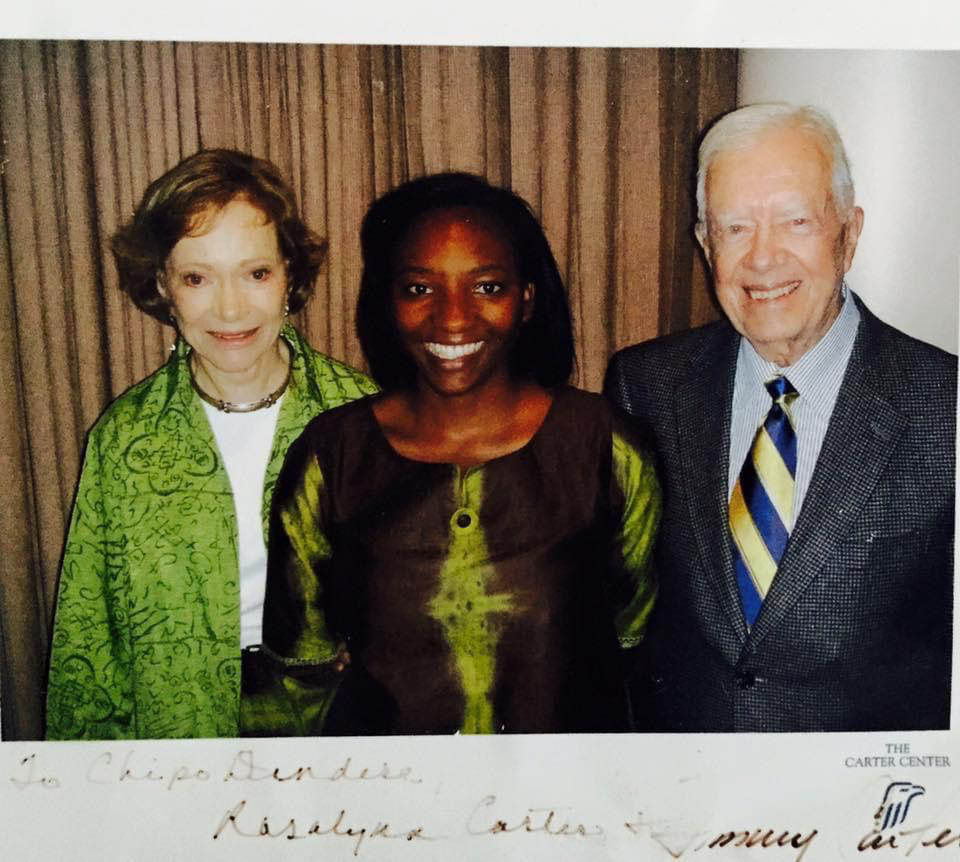

Photo courtesy of Politico