Standing in the middle of the Wellesley College new student orientation last August and seeing all of the Welcome Class of 2019 signs and yellow strewn everywhere, one would guess that the only new students in attendance were first-years. However, there were also twelve new transfer students who began their first week as Wellesley students this year. These students were a select group of sophomores and juniors from universities all over the nation and homes all over the world who came here in search of a fresh start and the new experiences Wellesley could offer.

These yellow class events that transfer students attended were the first of many instances that pointed out the ambiguous nature of being a new transfer student.

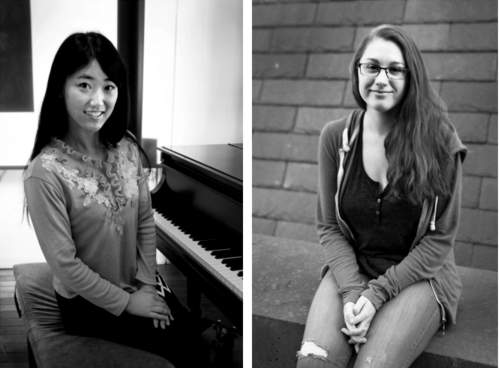

“I think our experience is different because we’re old, compared to the freshman, but we’re also new. So I think we’re in kind of an unusual position and being such a small part of the student population highlights the difference in our academic experience,” Amanda Kraley ’17 pointed out.

There are very few transfers accepted into Wellesley each semester.This puts them in an interesting position as they do not get all of the same privileges other upperclass students get but they are not fresh-faced first-years.

The transfer student acceptance rate is currently 10 percent. They have class standing as sophomores and juniors, but know little more than first years. This may result in missed opportunities, such as not getting to sign up for a specific class or not knowing about a networking event until it is over. Therefore, these students must work overtime to compensate.

“As a transfer student, I do not feel excluded, but a little disadvantaged by not knowing enough people on campus,” Cindy Heng Liu ’18, an international transfer student, said.

Finding their niches on campus, while difficult for fall-transfers, is even more difficult for spring-semester transfer students. This small group enters the school after Wintersession and does not get the luxury of a week-long orientation or an organizations fair. It can be a struggle for these students to figure out life at Wellesley.

Lorna Wu, ’16 spoke about her difficulties as a spring transfer student.

“The process was difficult because I arrived on campus without a support network. All spring-transfers lived in different halls, so we were isolated from each other,” Wu explained.

Spring-semester transfers share a weekend-long orientation with exchange students from Slater but do not get enough support as a group.

“Hence, our first impression of Wellesley was that it didn’t care about transfer students at all,” Wu said.

The transition process may be something of disappointment for the spring-transfers, but Wu is now overwhelmed with her euphoria here and served as the transfer-student mentor group leader this fall, welcoming a new group of transfers to Wellesley.

On the other side of the spectrum, many cite the fall orientation as being overwhelming. Liu admitted that while the orientation was fun, the activities were excessive and disconnected. Most events were geared towards first- time college students and face-time with administration was scarce. Liu also found the administration to be somewhat detached.

Fall-transfers are clumped together alphabetically as opposed to by interests/habits. Yet, like all new students, they must fill out the roommate preference form. The result is that they are paired with people with whom they may have little in common.

Wu also explained that spring transfer students may also find Wellesley’s grade deflation policy disheartening. This policy, which does not take place at most universities in the U.S., certainly takes some adjusting

“The grading policy was an issue because I work hard and my former college grading policy was easier. I was distressed by that for a while,” Liu admitted.

Kraley explained that she first knew pressures were high here when she saw two girls crying in a corner, and another girl screaming over a paper. This level of stress and competition, she noted, simply does not happen at most other schools.

The lower level of stress certainly appeared to be the case at University of Miami (UM), where Margaret Lees ’18 attended for her first year.

“UM has a sports centered culture and the campus is influenced by the Miami party culture as well,” Lees explained.

Here in “the bubble,” however, an overwhelming majority of the emphasis is on academics. Lees has found a way to look at the bright side of this situation.

“I feel like grade deflation will benefit me in the long run; it will force me to take the emphasis off my obsession with perfect grades and put my energy into learning as much as I can … at least, that’s what I hope,” Lees said. “Wellesley can be stressful, but even under a pile of deadlines and assignments, I find myself incredibly grateful that I can study here.”

The same applies for Kraley, who applied twice to get into Wellesley, first after her freshman year at New York University and then after her sophomore year at Boston University. Wellesley was her dream school, so she kept applying until she got in. Often, transfer students choose Wellesley because their former institutions were too big and impersonal. They felt as if they were just a number in a sea of thousands of undergrad, graduate students and

“Being such a small school, Wellesley does have an advantage. You’re treating a transfer pool of 12 compared to a school such as BU, which had a transfer pool of about 3,000,” Kraley pointed out.

Lees agreed, finding that introverted people may struggle more at a larger university. Although many transfer students find the grade deflation shocking and the environment different from what they have experienced at their other schools Liu, Kraley and Wu find that because of their previous experience they are able to provide a unique perspective on the Wellesley experience.