Scientists in Britain are waiting for consent from government officials to carry out a procedure that will allow a baby to be born with genetic material from three people. Though this genetic manipulation is intended to cure hereditary mitochondrial defects, many are expressing ethical concerns about this experimental procedure.

A fear of eugenics has existed ever since the discovery of gene manipulation. Eugenics is the science of improving the human population by controlling for desirable hereditary characteristics. Controversy lies in what constitutes a desirable characteristic and who gets to decide this.

Despite these dilemmas, there are those who see genetic manipulation as an instrument of good. These people include a team of scientists working in Britain at Newcastle University. This team, lead by Dr. Doug Turnbull, is focusing on finding a way to combat the devastating effects of defective mitochondrial DNA. The organelle mitochondrion is a crucial part of all human cells. These organelles are the sites of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production. ATP provides “energy” for the cell and is essential for many molecular processes.

Interestingly, mitochondria have their own DNA. It is widely accepted that this is because mitochondria were once independent organisms, slowly developing from symbiont to a true, inheritable part of the cell. Because humans inherit their mitochondria, the mitochondrial DNA is derived from their mothers. In most cases, this fact simply provides an interesting connection to a person’s maternal history, should they want to explore it. For some potential mothers, however, there is a fear of passing on defective mitochondrial DNA to their children.

Though the severity of these problems can vary, babies who inherit mitochondrial defects often die just weeks or months after being born. Their cells cannot harness usable energy and therefore waste away. In order to prevent these tragedies, Dr. Turnbull and his team have come up with what they see as a potential solution for the problem.

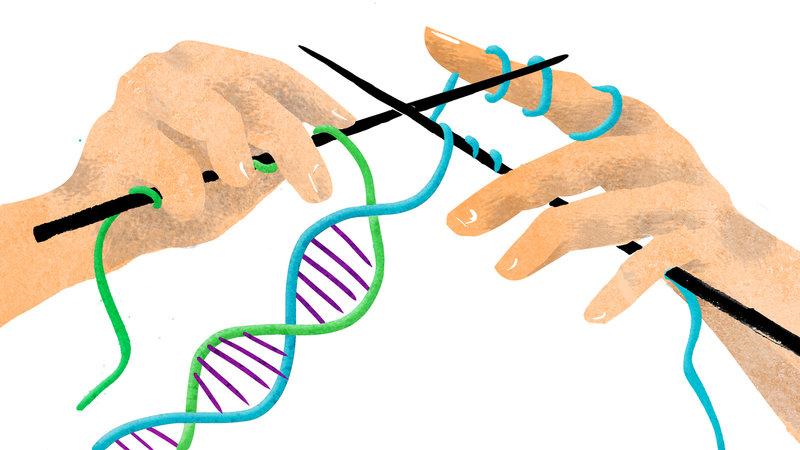

It is possible to collect healthy eggs from a woman with working mitochondrial DNA, fertilize it in vitro and then remove all of the DNA from the nucleus while leaving the healthy mitochondria behind. This nuclear DNA is the genetic material most people are familiar with. It determines hair and eye color, height and other characteristics. Once this nuclear DNA is removed, it can be replaced with the nuclear DNA from an embryo created by the would-be parents. This combination results in an embryo with both healthy nuclear and mitochondrial DNA.

There is, of course, a return to the question of ethics. The embryo contains the genes of three people, though in varying amounts. Additionally, the procedure is intended to improve a potential human being. Though it may not seem like a bad thing to prevent the premature death of a child, some worry this would set a dangerous precedent for the creation of so-called “designer babies.”

One such critic is David King, a molecular biologist who runs a watchdog group called Human Genetics Alert.

“You’re making changes which we may not know the actual consequences until that person is born, which could include damaging effects on that person’s health,” King said in an interview with NPR. “Those problems would be passed down the generations to that person’s descendants. And obviously that’s something that you don’t want to do.”

Due to these concerns, this procedure is being reviewed by British government officials, and their decision will determine whether the experiment is allowed to continue.

There is a strong and often valid fear of carrying out such experimental procedures on humans when the long-term effects are virtually unknown. Despite concerns, a new age of human reproduction is beginning, and this will not be the last case where ethics must be weighed against scientific capabilities.