As millennials running the competitive race to the top, we swallow stories of failure and success thirstily, desperate to quench our ambitions and survive the daunting distance between our current inadequacies and ultimate goals. We huff and pant over figures like Steve Jobs, who dropped out of college, lost his own firm and still transformed the world of technology, and JK Rowling, who published her bestselling series after several rejections.

We waste our breaths in sharing stories of millionaires who scattered a trail of failed startups in their wake, of athletes with damaged ankles and knees who later seized a handful of Olympic medals. Failure sticks to our sides like an old, albeit irritating, friend – we link arms and cheerfully stumble our way to the finish line.

The public demands failure. Understandably, no one wants to hear about someone who calculated each detail, equipped themselves properly and emerged successful with no embarrassing stories to share over midnight cocktails. The problem here is not only society’s selective self-validation – in choosing to ignore “dark matter” in favor of stars, or the majority whose failures lead nowhere – but also the prevalent idea that persistence trumps over all, regardless of class, gender, and race.

Failure has become the catchphrase of the upper middle class, who possess the wealth, connections and background to experiment and err; furthermore, they risk little when they announce their former struggles, unlike minorities or disenfranchised members of society whose failures are often attributed to inherent laziness or incompetence.

We need to shift conversations of failure away from inflated rhetoric of individual persistence and trial and focus instead on breaking barriers, in addition to acknowledging the level of privilege that comes with failing one’s way to success.

The concept of trial and retrial prevails in startup culture, where many budding entrepreneurs flaunt their failures like Boy Scout patches, but refuse to acknowledge the same privilege in people of disenfranchised circumstances. Kate Losse highlights the infatuation with failure in the New York Times, arguing that “telling the story of what went wrong is a way to wring insight from failure, but it’s also a way of proclaiming membership in a community of innovators who are unafraid of taking risks.”

A successful entrepreneur charms her way into the desired industry and obtains millions in investment for her business, and as much as we love to imagine Silicon Valley as the egalitarian playground for innovators, where a wide-eyed, unconventional businesswoman with a zest for big ideas and witty turns of phrase can launch a billion dollar company, the nitty-gritty reality works differently.

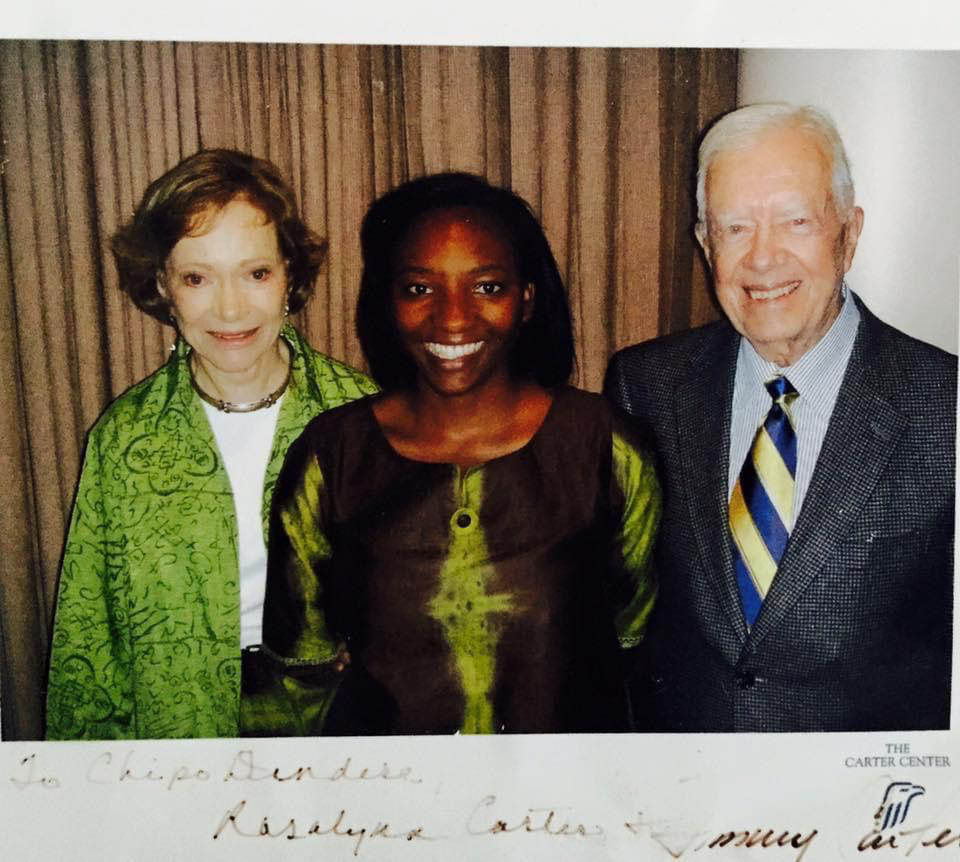

The ones with the most access to capital and networks are upper-middle class white men from elite universities who are already part of an unofficial fraternity formed around startups and tech firms. According to Losse, research firm CB Insights reports that of all Internet startup founders who have received significant venture funding, 87% are white, and that black women raise a paltry $36,000 as opposed to the $1.3 million that funds the average startup.

Of course, the statistics do not take into account comebacks from failures – data already shows that minorities are less likely to receive funding for their startups and are even less likely to receive another opportunity after a failed startup.

In part, this results from ingrained prejudice within society; while a history of aborted startups can boost a young, white man’s proposal, the same damages any chances a woman or a minority may have. A male entrepreneur can boast his failures because they indicate his enthusiastic, risk-loving nature, while a female entrepreneur even with a shorter list of errors, is unreliable and incompetent.

Our scrutiny of failure bleeds into academia or college life as well – for many of us, failure, or an inclination to experiment, is simply not an option, because we carry the burden of representing our entire ethnicities or gender when enacting the smallest labor. It is too easy for people to taunt the failures of minorities while pedestalizing those of a select group. The discrimination can take forms in subtler ways – for example, those on financial aid or college scholarships often have to tread cautiously, because a single failure could snatch away their chances at a brighter future. “Model minorities,” on the other hand, are expected to perform better than the majority – for them, the bar for failure is set much higher.

The millennial age invites only a select few to fail, and by extension, to explore different options and learn through mistakes. We know society has progressed when failures become milestones instead of egregious imperfections, but at the current moment, failure has become a privilege instead of simply an inevitable human condition. The focus on individual persistence and courage in face of failure has its merits, but detracts from important discussions on how to overcome exterior barriers to success.