In a world that still seeks to legislate women’s sexual and reproductive rights, Wellesley College offers a unique space for women to embrace and discuss their sexuality. Wellesley works towards an acceptance of women and gender-nonconforming student’s sexual urges regarding men, but often fails to address the darker reality of sex: unethical pornography, sex work, the intersection of sexual expression with race, religion and accommodation for sexual assault victims. We must remain vigilant and critical regarding sex-positivity and its implications. We need to rethink the way we talk about sex by acknowledging two things: one, freedom to choose does not necessarily entail or even demonstrate freedom from patriarchal influence, and two, engaging in frequent sex and ‘kinkiness’ is not an option for everyone.

A 2014 study published in the Archives of Sexual Behavior revealed a negative correlation between the amount of porn men watch and the satisfaction they find in intimate relationships. Aside from negative effects on real-life relationships, pornography often combines sex with violence, frequently showing the physical humiliation and debasement of women, and one of the most popular categories of 2015 is ‘teen.’ The popularity of barely legal teenagers should disturb us all, especially when one considers that 67% of men aged 31 to 49 have admitted to watching porn at least once a week, and that there are 116,000 searches on child pornography daily. This does not even go into the trauma and abuse faced by adult video (AV) actors and actresses; according to a UCLA study in 2014 that looked at 366 performers, one in four pornographic performers has had gonorrhea or chlamydia, while more than 16 percent reported that they had experiences where they did not receive pay for their work. The study, focused on a small but significant pool, reflects a larger trend in the porn industry and reminds us that not all involved in the industry are mindful of performers’ sexual health and safety, or even respectful. Unfortunately, discussion concerning pornography at Wellesley rarely extends beyond the ‘choice’ argument. Arguing that pornography is ethical because its consumers and workers choose to engage in it erroneously assumes that the larger patriarchal system has no influence on people’s choices.

Pornography brings up another uncomfortable side of sex-positivity: the way patriarchy bleeds into the bedroom and other aspects of intimate life. While the environment at Wellesley encourages informed consent and exploration of one’s sexuality, it also refrains from conversations about the role of sex within romantic or sexual relationships. Too often, the media informs women on how to please their boyfriends or husbands without taking into account women’s sexual anxiety or desires. The Wellesley community needs to talk about the lack of communication and resulting power imbalance within relationships, especially when society and media press women to be uncomfortable for the sake of their male partners. Wellesley students should consider some questions: how important is sex in a romantic relationship, and is there a pressure on young women to conform to certain sexual expectations with which they may or may not be comfortable? If so, how do we ensure that ‘choice’ or ‘consent’ are not just extensions of male sexual desires and whims?

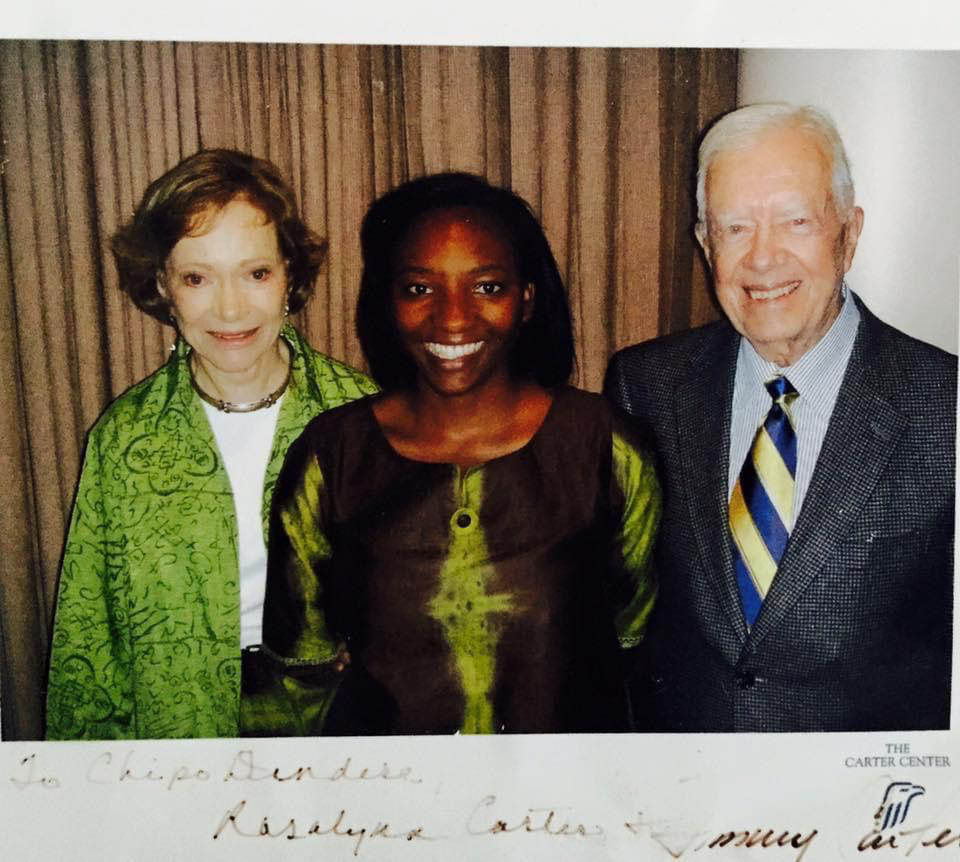

On a broader level, the sexual discourse at Wellesley caters mainly to a specific subset: upper-middle class, white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant or atheist. The uncomfortable truth, the underlying hypocrisy of sex-positivity, is this: more often than not, a sexually active white woman will not face the same kind of public defamation her nonwhite counterpart would face, simply because the bodies of women of color are hypersexualized and degraded in a way white women cannot perceive. Of course, the issue extends beyond race; women who face greater financial struggles cannot afford birth control or other preventive measures that would make a healthy, sexually active life possible. Furthermore, the pressure to engage in casual sex alienates women who may wish to remain sexually inactive for religious or personal reasons; the discourse at Wellesley mainly caters to women who frequently have sexual relations with men, and not to abstinent or gay or transgender women. The first step towards a collegiate environment that is truly sex-positive is inclusivity. Before lauding its own sexual freedom, Wellesley needs to start incorporating the narratives and experiences of those who do not fit into an acceptable category, whether they be virgins, religious, queer, or abstinent.

There are many narratives that exist at Wellesley regarding sex, especially those that are not exactly celebratory of it. The solution is not to sweep discourse of intimate matters under the rug of ‘choice,’ but to allow ourselves to talk freely about pressing concerns generally avoided in the real world.