The cornerstone of the liberal arts education is developing critical thinking skills fostered by the free exchange of ideas. In recent years, the culture of this institution has become increasingly intolerant and unwilling to engage in conservative dialogue. In some ways, our sensitivity has made us reluctant to examine the world outside of ourselves.

In its letter, The University of Chicago upheld its “commitment to freedom of inquiry and expression.” As a result, they no longer condone the display of trigger warnings. By definition, a trigger is anything that provokes a negative emotional reaction, most often towards those with post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. Victims of PTSD can be triggered by anything from smell to noise and thus must be treated with sensitivity. In fact, higher educational institutions should have the obligation of providing their students with the resources to combat and overcome their difficulties. What the institution fails to realize is that you can be egalitarian while also supporting free speech. Providing such information gives everyone an equal chance for success and comfort.

At the same time, it is unfair to say that everyone who has suffered from trauma benefits from trigger warnings. In a 2015 letter to The Atlantic, one woman argued that the lack of one had actually helped her overcome a family suicide. Not having the warning, she asserted, allowed her to openly discuss the content. In addition, she believed that she had finally been treated like everyone else, and the experience allowed her to move past the personal obstacle. Therefore, it is important to acknowledge that confrontation may be a solution for some, though it fails for others. No individual can decide what is best for another’s mental health, which seems to be the attitude we have adopted lately. Perhaps to better support our community, we ought to reevaluate the way in which we present triggers.

In addition, a 2015 article in The Atlantic, “The Coddling of the American Mind,” discussed the adverse effects of trigger warnings on mental health. According to social psychologists, “avoiding what you fear is misguided,” which suggests that trigger warnings are, in fact, counter-productive. Instead, they advocate for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a treatment which forces patients to focus on common distortions in their everyday lives, and therefore see the world more accurately. Such critical thinking skills, especially in relation to your own emotions, are the fundamental values higher education seeks to impart.

We do not denounce trigger warnings in this article. Rather, we mean to suggest that people recover from traumatic incidents in a variety of ways. Although we treat TWs as a panacea for mental illness and trauma, the solution is not so simple. We must use them responsibly, by exploring and understanding methods of recovery before resorting to evasion. Together, we should reconsider our approach to content labels.

At various colleges, students have demanded trigger warnings be placed on art and literature, so that they can be avoided. Not long ago, Wellesley College removed “The Sleepwalker,” an art installation of a naked man placed on campus grounds after it was deemed triggering. Additionally, the work of art, which was the creation of living artist, was vandalized by a student on campus. At Columbia, an English class demanded labels on “Mrs. Dalloway” and “The Metamorphoses” for mentions of suicide and sexual assault, respectively. Art and literature, by their very nature, are meant to provoke emotional responses, prompt critical discourse and, at times, inevitably incite controversy.

For much of human history, such mediums have fomented revolutionary and productive dialogue. Consequently, trigger warnings have had the effect of placing a lens over articles, speeches and other forms of information, influencing our perceptions of uncomfortable subjects and thereby detracting from intent and message of the piece. By priming the students’ minds with this sort of expectation, confrontation with the same issues post-graduation may even exacerbate their emotional responses.

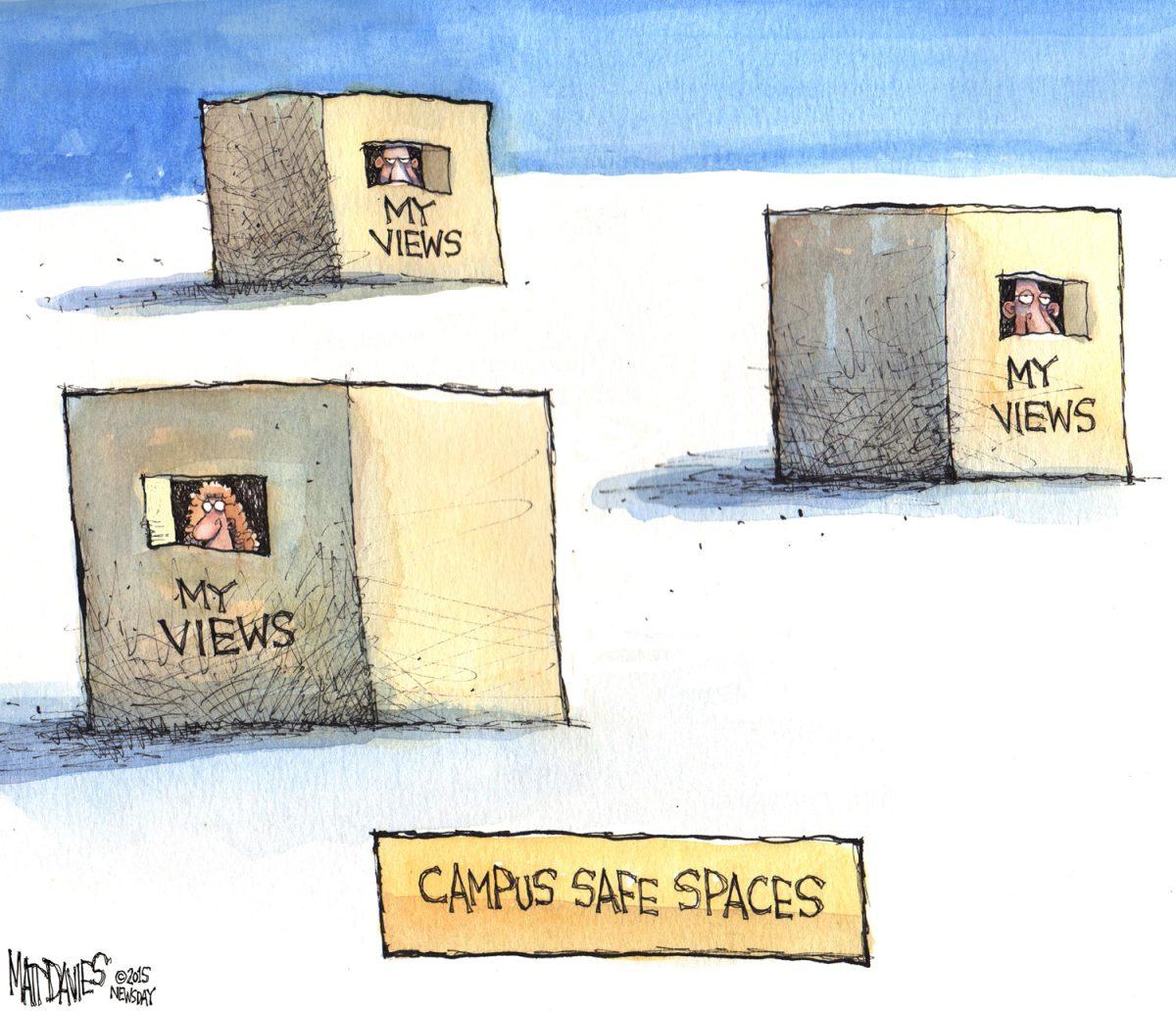

The University of Chicago continued by criticizing “intellectual ‘safe spaces’ where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.” The minority opinion of the Wellesley News maintains that safe spaces are important places for reflection and discussion, but only in specific situations. In areas of dialogue or discourse, such a label infringes on freedom of speech by indicating that the opinions of some are valued more than others. This in itself constitutes an issue in a higher education institution that promotes the free flow of ideas amongst its student body.

The Atlantic noted that safe-spaces are “creating a culture in which everyone must think twice before speaking up, lest they face charges of insensitivity, aggression, or worse.” Our cultural definition for safety has devolved into the absence of contrasting perspectives rather than a place for respectful discourse. On various college campuses, students have used safe space as a blanket term to exclude controversial speakers, journalists and even political organizations.

Even if an opinion is far from one’s personal beliefs, engaging with controversy allows students to separate their personal thoughts from derived ideologies. It is our academic responsibility to investigate the opposition, especially if we are to be culturally, socioeconomically and politically diverse. In theory, although safe spaces are simply areas where like-minded individuals can reflect on pertinent experiences, they have, in practice, become places that do not welcome the opposite opinion.

Isolating oneself from opposing viewpoints is dangerously counterproductive. In an article for New York Magazine, author Jonathan Chait asserted that the “left is proposing to change the norms of discourse within progressive spaces in a fundamentally illiberal way.” That is, students use safety as an excuse to suppress dissenting ideas. You can have a safe space in a place of sharing experiences, at a talk-back or in a gathering. However, calling a debate a safe space suggests protections for a minority opinion, thereby fostering intolerance for a counterpoint. We too often define safety as protection from the opposition, shielding us from understanding the arguments of those around us. Respect can exist in a debate setting, as it should. Nevertheless, everyone’s point of view should be challenged and argued with.

College is an opportunity for us to gain exposure to a multitude of ideas and viewpoints, so that we may better develop and understand our own. Banning controversial speakers on the principle that they might discuss disagreeable topics does not in fact protect these students, but counterintuitively shields them from some of the realities of the world. Of course, such talks should be optional, but is essential for us to understand that opposing points of view are valid and permissible. Engaging with the counterpoint will allow us to be more productive members of society by promoting a diversity of opinions. Intellectual rigor and challenge is the cornerstone of social change.