The Zika virus continues to dominate the news cycle as new information emerges about its effects, its transmission and attempt to find a cure.

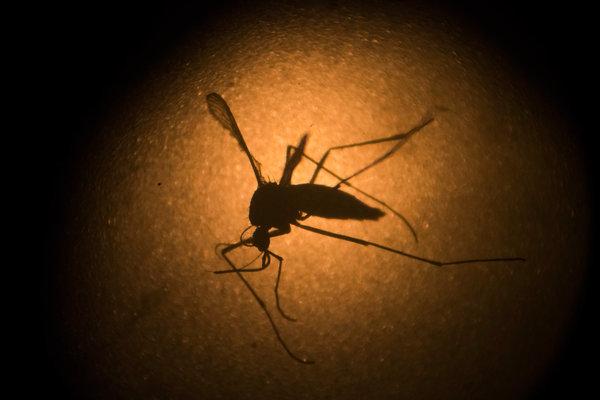

Zika is a virus transmitted through infected mosquitoes of the Aedes species. It has recently been found that the virus can also be transmitted sexually. Though the virus usually causes an unpleasant, feverish disease similar to dengue fever, it is manageable in many groups. For many people, however, the most concerning aspect of Zika is the effect it has on unborn fetuses. If a pregnant person contracts the virus it can be transmitted to the fetus with very serious repercussions, namely microcephaly.

Because the virus is most common in a swath of countries around the equator, the current WHO policy is that couples in these countries should have access to birth control and receive information regarding the potential risks of becoming pregnant while Zika is a threat. The CDC has campaigned for contraceptive donations to Puerto Rico from corporations in the United States and has advised that pregnant women avoid traveling to high-risk countries.

Unfortunately, the danger of Zika infection and microcephaly cannot always be forestalled. It has been discovered that the virus can stay active in sperm for up to six months after infection, even if the infection is devoid of symptoms or if the person has recovered.

Many drug and vaccination companies are rushing to research a Zika vaccine, but the product cannot be realistically expected for several years. One issue researchers face is administering the vaccination to pregnant people. This means that the ideal vaccine would be of the inactive variety, meaning that the viral particle used to stimulate an immune response would be grown in a lab and then killed off before being used in the vaccine. And, like in any drug or vaccine development, there is a stringent process for gaining approval to actually produce and distribute the treatment. This involves multiple trials that last for years to test for longer range effects. Other prevention techniques include genetic recombination, which makes the virus inactive through a modification to its genetic material (often RNA).

Of course, these long range trials also require funding, and there is currently a crisis in funding for Zika research and prevention. The CDC has been bankrolling many research projects and efforts to spray for the Aedes mosquitoes in places like Florida. However, Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the head of the agency, recently told reporters the CDC had spent $194 million of the $222 million allocated to fight Zika. Congress scheduled a vote to allocate more funds to fighting and researching the virus, but it was blocked due to political concerns about additional attachments to the bill. The attachments included a stipulation that Planned Parenthood could not contribute to the effort to provide contraception and education surrounding the sexual transmission of Zika. This has made the issue of Zika funding profoundly political, and has contributed to the stall in fund replenishment.

The National Institutes of Health, as well as several international corporations and private companies, have begun testing of potential vaccines. Inovio Pharmaceuticals has one that is approved for human trials in 2016. Moving forward, the issues of funding will be continually revisited and the world will wait for results of the clinical trials that have begun in the search for a vaccine.