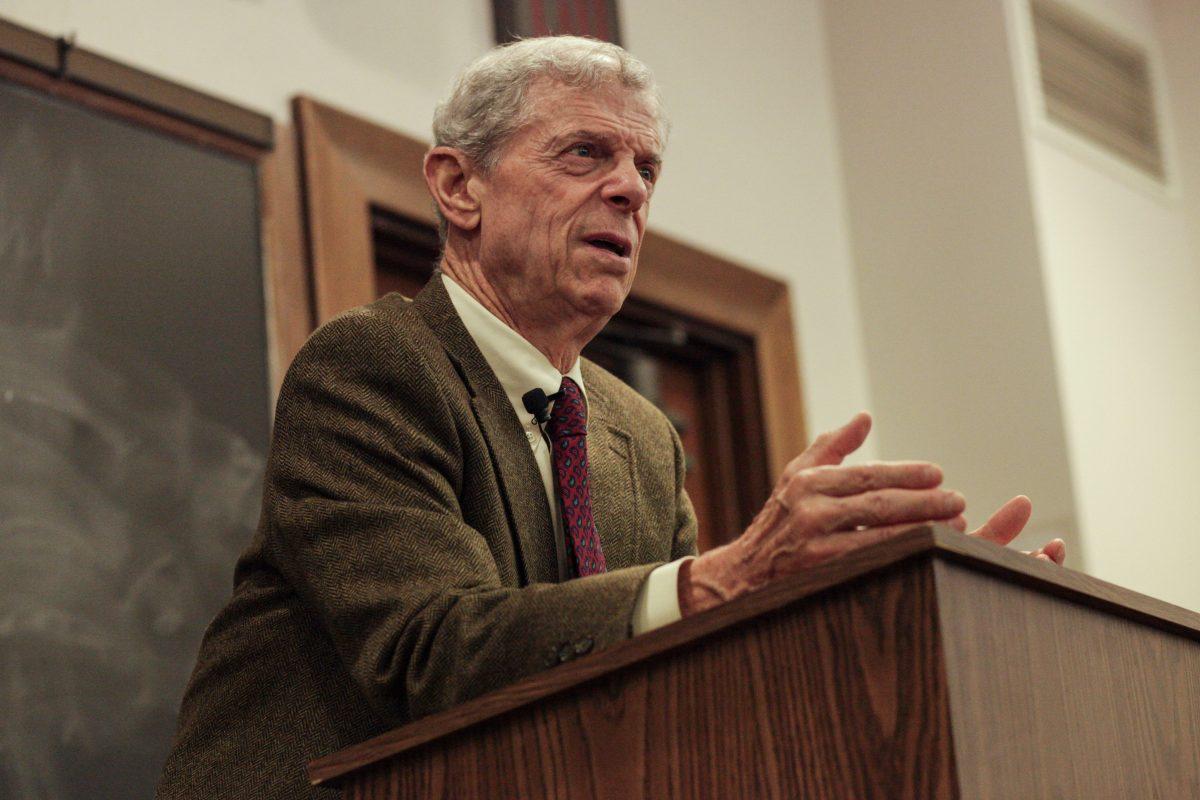

Peter Davis, Academy Award winning filmmaker, has always wanted to write a novel. As the son of two screenwriters, his home was filled with literature and scripts to be discussed around the dinner table. “I had lots of writers in my life, including my first wife, and I always enjoyed their company.” Davis reminisces fondly as he sinks into the plush sofa of the English department common room.

What makes Peter Davis so richly unique in the world of creative expression is that he seems to have a natural affinity for any project on which he embarks. He has worked for the New York Times, CBS News and PBS, and written three successful nonfiction books. His documentary film, “Hearts and Minds,” won an Academy Award in 1974 for its vivid portrayal of the Vietnam War. So when, at the age of 78, his first novel came onto the scene, many were delighted—and a little surprised.

“Girl of My Dreams,” published in 2015, takes place in 1930s Hollywood when both the Great Depression and the Communist Party weighed heavily on the hearts and minds of the American public. In Davis’ novel, a hopeful young screenwriter named Owen Jant navigates this scintillating world of movie stars, tycoons, murder, romance, strikes and scandal. With snappy fresh prose Davis loads his book with iconic images from Hollywood’s Golden Age, making it a thrilling and informative read. “I had heard a lot of stories growing up about this golden age of filmmaking that coincided with a decidedly un-golden age in the country around it. And I wondered how these two things could coexist,” Davis explained when asked about his intention in writing the book.

Last Tuesday, I sat down with Davis before the book talk being hosted by the English Department to talk about his intriguing career path. He maintained that after reading every single issue of the daily show-business publication “Variety” from 1933 to 1935 and extensive articles and books, the story he was trying to write couldn’t be nonfiction. “What I realized was that all these articles and books about the ’30s never really got inside the minds of people who lived in those days. If I wanted to get inside, I would have to make it up! So my new reality, at least the truth as I was able to tell it, became my novel.”

“Her star had risen,” Davis writes. “By 1934 she was who women wanted to be. And men wanted.” In this quote Davis introduces the controversial character of Palmyra Millevoix, a multifaceted woman working as an actress and songwriter in the novel. Naturally, the conversation drifted to women’s roles as writers and actresses in the film industry. “At the beginning of the silent film era, most of the screenwriters were women because they wrote stories that other women wanted to go see. And also, actresses were just as important as actors back then—everyone would go to see a movie just because it had Greta Garbo or Joan Crawford. They don’t go now to see a Julia Roberts movie. That isn’t the way it works. Even great stars like Roberts or Streep are usually in movies with a male co-star who gets paid a little bit more. It’s terrible.”

When asked why, Davis accredited this to the shift in entertainment from large movies to the myriad of streaming options available at our fingertips today. He talked about “tentpole” movies, industry jargon that is used for the five hundred million grossing movies like “Batman vs. Superman.” “These films are made to appeal to males aged 14-20 because they know that those kids will not just see them once or twice—they’ll go five times! I know, of course, there are girls that see them too, but the industry assumes the boys have brought the girls along. Unfortunately, women screenwriters just aren’t generally hired to write these blockbuster action movies.” Davis lamented the dearth of female screenwriters in Hollywood, and named Nora Ephron, an old friend, and Anita Loos as two of his favorites.

The book talk itself began with glowing introductions by Professors Yu Jin Ko, Yoon Sun Lee and Marilyn Sides of the English Department. They praised Davis’ prolific career along with his keen ability to capture the essence of many of America’s historical moments.

Davis, full of charm and quick wit, talked about his family’s experiences in California. “My parents didn’t really like Hollywood. They always said it wasn’t interested in reality, blew smoke, had unrealistic expectations and everyone wanted to get rich. So when I finished majoring in English at Harvard I went to work in journalism, partially to get away from the make-believe world my parents were writing for and partially because I thought that was what really mattered—facts. I was wrong about that. Reality is also poetry; it’s W.H. Auden and Elizabeth Bishop.”

Davis read aloud excerpts featuring the unfortunate demise of a stuntman, songs written by the beautiful Palmyra Millevoix and even an erotic telegram, much to the delight and amusement of the audience. Afterwards, Davis opened the floor to questions from the crowd. He was asked about his writing process, the effect of including a romantic storyline in such an era and, in classic Wellesley fashion, the validity of Palmyra’s humanity under the guise of such an idealized female figure. Perhaps not quite expecting such intense questioning, Davis seemed flustered but ultimately impressed by the audience’s queries.

Davis has a deeply personal connection to Wellesley and has loved it all his life. His aunt was a student during the time Madame Chiang Kai-Shek was attending. His first wife, Johanna Mankiewicz Davis graduated in 1958 and there is now a prose prize given to the best short stories every spring in her honor. His daughter Tonia Davis, now vice president of Chernin Productions—responsible for many episodes of “New Girl,” “Ben and Kate” and “Terra Nova”—is a member of the class of 2004. On the subject of Wellesley, I asked Davis what specific advice he might have for the aspiring authors and filmmakers at Wellesley.

“For an aspiring author—read, write and major in something that interests you. It doesn’t necessarily have to be English or Comp Lit, but something that really interests you. Majors like anthropology and history mean you’re going to be reading great texts anyway.” The novel and story writing will follow, he assures.

“For filmmakers,” he chuckles, a mischievous gleam in his eye, “I have a somewhat unorthodox piece of advice—DON’T major in film. Film is only one hundred years old. Take the wonderful film courses at Wellesley, but just don’t major in it. Major in a field that has a collected body of knowledge and work going back centuries. It doesn’t even necessarily have to be within the humanities—there are good filmmakers that majored in physics! But most of all, look at the great films of the last century and get out there with a camera.”

Davis’ zeal for his craft and his unwavering confidence at following his instincts make his newest endeavor ring as genuinely as “Hearts and Minds” did back in 1974. Whether exposing the realities of warfare on the battlefield, authoring nonfiction books on Nicaragua and small-town America, or imagining the daily happenings within Hollywood, Davis brings the energy of a director and the vision of a master storyteller. Those harboring ambition to break into the world of film, nonfiction or fiction can all find inspiration in Peter Davis’ extraordinary career.

Photo by Audrey Stevens ’17, Photo Editor