In the past several years, scientists and doctors have been exploring ways to treat cancer with immunotherapy, a treatment plan that uses a person’s existing immune system capacities to fight cancerous cells in the body. Scientists know that the immune system is able to prevent the majority of cancers from taking hold. The cancer cases that go on to harm or kill are the few that slip through the immune system defenses. Strengthening the immune system could be one way to combat cancer.

Doctors and patients want to explore this type of treatment in order to delay having to use chemotherapy. Because many cancer treatments decrease the quality of the patient’s life, there is a strong incentive to find treatments that are less damaging and more effective. At the very least, doctors could rely on a combination of treatments to lessen the effects.

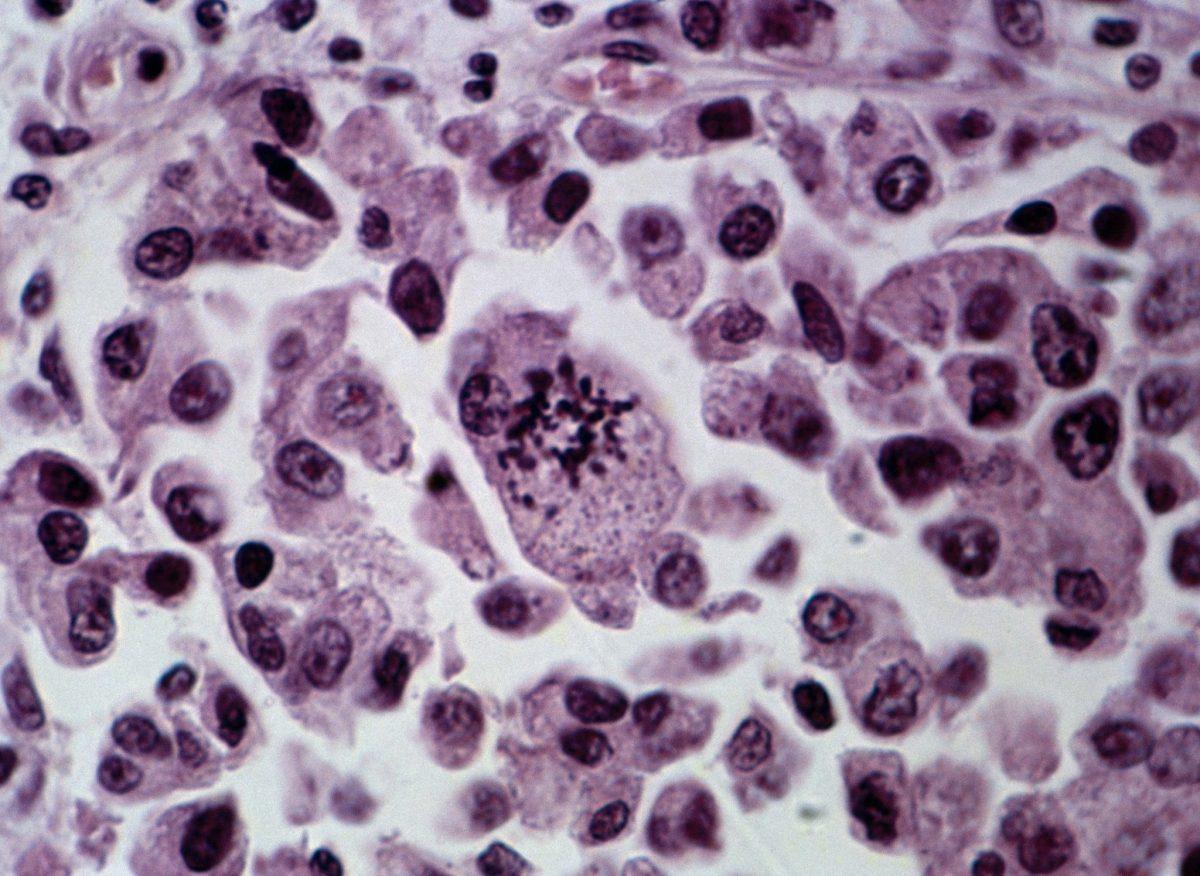

There are two main types of immunotherapy that have proved most effective. The first is called chimeric antigen receptors (CAR) T-cell therapy, an experimental form of therapy that engineers T-cells from a person’s own body so that they recognize and attack specific cancerous cells.

The second type of immunotherapy is called checkpoint inhibitor therapy. When the body’s cells are functioning properly, there are checkpoints built into the immune system to prevent the body from attacking its own cells. Failures in this system result in various autoimmune diseases like diabetes. Cancerous cells can also send out signals to turn off immune responses in these systems in order to promote cancer growth. Drugs for checkpoint inhibitor therapy help to reactivate the immune response so that the body can effectively fight cancerous cells.

These treatments may play a significant role in the fight against cancer, but there are problems attached to immunotherapy as well. Most significantly, it does not always prove successful and scientists cannot figure out why. For example, CAR T-cell therapy seems to be very effective on blood cancers like leukemia and checkpoint inhibitor therapy serves as an effective option for melanoma. But this is not the case for all melanoma patients, and certainly not for all cancer patients. A trial of the drug called Opdivo, for example, was ended in its early phases because there was not enough of an effect on lung cancer patients for it to be a viable option.

Additionally, the risks of these treatment forms are uncertain. While people are often well-acquainted with the negative side effects of chemotherapy, they know little of immunotherapy’s potential drawbacks. For now, some evidence suggests that it may cause chronic arthritis and fatigue.

In part because of these imperfections in the immunotherapy realm, scientists and healthcare professionals are exploring options for more personalized cancer treatment. They are investigating the reasons why immunotherapy works on some people and not others.

Current theory says that patients with higher levels of checkpoint proteins respond better to checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Another possibility is that the order in which drugs should be administered during treatment needs to be better determined. Despite these unknown factors, immunotherapy and other alternatives to chemotherapy and radiation seem to be taking over the conversation about how to treat cancer more effectively.