When U.S. politicians, performers or celebrity figures attempt to paint themselves as morally righteous, they often do so by asserting their adherence to Christian values. Since 83 percent of Americans identify as Christian, this move may be motivated more by pragmatism than honest religious fervor. Nevertheless, these discussions seem to have made morally good acts of love and compassion tied to religious tradition to the extent that those who act lovingly and compassionately are assumed to be religious.

Certainly these conversations aren’t unique to U.S. celebrity culture. Since self-identified atheists constitute approximately 13 percent of the world’s population, it’s safe to say that most world leaders and activists either honestly practice a religion, falsely assert themselves to be practicing a religion or are uncomfortable admitting their lack of religious devotion. These numbers are not troubling by default. Religious institutions and spiritual practices play a significant role in improving elements such as individual communities, humanitarian causes and even mental health treatments. However, when religion comes to be tethered to morality such that a lack of religious tradition entails a lack of moral righteousness, we should be critical. This conflation of religious or spiritual devotion with respectable morals is a problematic one.

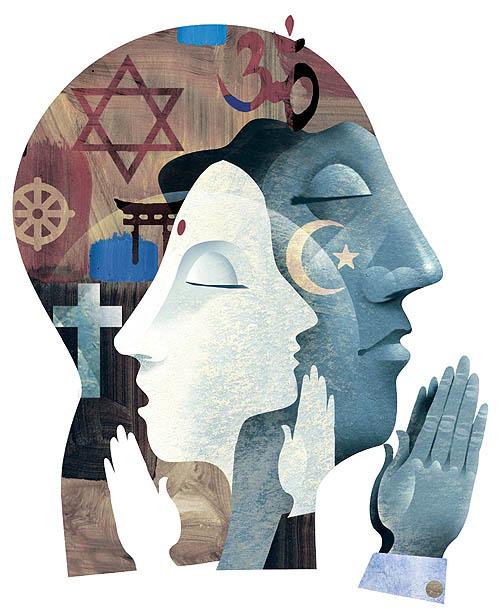

Even when read solely for historical inquiry, it’s hard to deny that texts such as the Bible, the Bhagavad Gita, the Torah and the Qu’ran all seem to be offering some sort of guidance for living one’s best life. While religious teachings are certainly capable of offering moral guidance, all ethical guides do not exist solely as a result of religious doctrines.

In order to separate religion from moral righteousness, it seems necessary to first define what exactly a religion is. While the diversity of worldwide religious thought is nearly unfathomable, for pragmatism’s sake we can define a religion as a system of faith and worship that involves some form of deity or deities. Thus western moral philosophy, which clearly lacks both deities and worship, seems to be an easy case for preserving ethics sans religion. Of course, religious thought precedes both western moral philosophy and other ethical paradigms. We could argue extensively about whether moral virtuousness existed before religious thought was formalized or whether modern ethical theories could have risen without their religious predecessors. However, I think it’s safe to say that at least in the present day and age, there must exist some non-religious methods of moral guidance.

The limits of human cognition prevent us from fully understanding the morals of others. With an awareness of these inhibitions in play, I’d argue that our window of perception lies in watching those around us prioritize. ‘Prioritize’ doesn’t mean simply to prefer one thing over another, but to place something at a level of fundamental importance. Most often, people whom we claim have admirable morals are those who prioritize empathy, compassion and love over self-absorption and vengeance. We admire these priorities because of a seemingly unspoken consensus that those admirable choices aren’t natural. When relationships fail, ideas don’t materialize or families separate, it takes effort and motivation to respond empathetically. Empathy necessitates an attempt to comprehend emotions other than our own and act accordingly, an effort that requires children to learn it and adults to practice it.

For 87 percent of the world’s population, this motivation likely has spiritual underpinnings, whether through explicit teachings or implicit cultural agreement. For the other 13 percent, these motivations must come from elsewhere. It seems untenable to entertain the idea that this 13 percent simply accounts for the portion of the population that lacks morals entirely. I don’t think I’m alone in attesting that some of the most loving people I’ve known have been agnostic, and I’ve certainly met some seemingly not-so-righteous people who have been religious devout. If loving is a morally good act, then those agnostics certainly aren’t in moral deficit.

How exactly ethics and religion are conflated is difficult to comprehend. It may be a centuries-old issue, but it is one that we should continue to examine with a critical and nuanced eye. It takes no more than a case study to prove this issue to still be a live controversy. Suppose there are two women volunteering at a hospital. Each woman has taken substantial time out of her weekly work schedule to do room visits, and each woman exudes an equal amount of thought, love and compassion to each patient. One of these women is a Christian, and she asserts her faith to be the motivation behind the joy she finds in her work. The other woman is an atheist, whose love for her work comes from an affinity she has for volunteerism and social interaction. Is one of these women more morally righteous than the other? The conclusion is not obvious. Rather, it seems there is ample room for discourse. If these conversations are open, then religion and ethics are not to be conflated.