In Professor Wes Watters’s office in the Whitin Observatory, the emblems of a life of learning and passion are the meteorites, little fragments of the cosmos scattered in boxes and arranged proudly on a tiered shelf. These remnants of geological processes here on earth and far out in the solar system beckon visitors to recall the universe’s vastness.

The image of a conventional office punctuated by little bits of wonder suggests something about Watters’ work. He researches “impacts,” collisions that occur at tens of thousands of miles per hour to create impact craters. Not only are these the most prevalent geological feature in the universe, but this process is also, he says, “the most fundamental geophysical process, because this is the process that built the planets.”

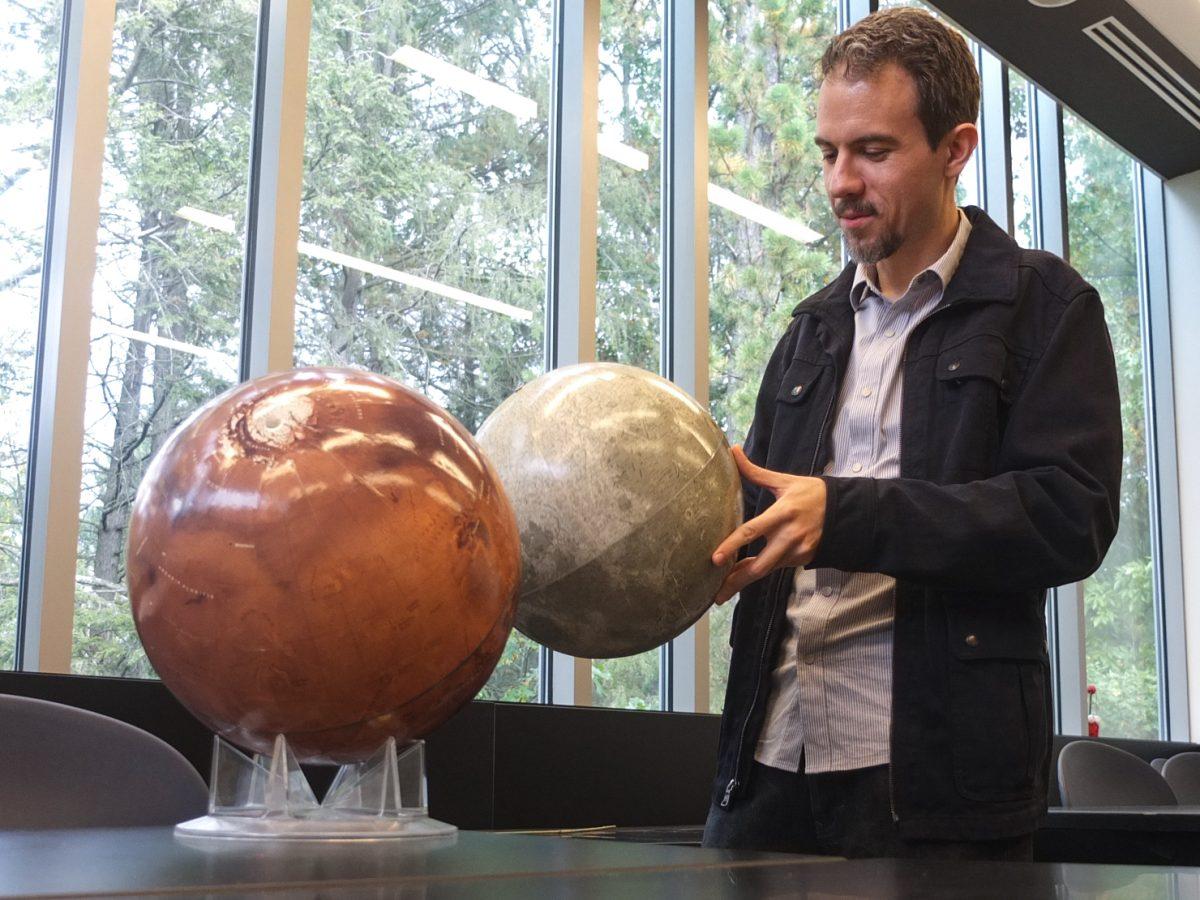

Watters’s research includes fieldwork at earth’s impact craters, most notably Meteor Crater in Arizona. However, he uses mainly spacecraft data; makes 3D models from images made by spacecraft orbiting around Mars and the Moon; and runs and analyzes computer simulations of impact crater formation. New missions like the Mars rover, Curiosity, provide new data for his projects.

Watters, who is originally from Oregon, received his degrees at MIT. In the first semester of college, he took a course in the Philosophy of Science thinking that the class would confirm his ideas and cement his conviction that, through science, one could find the answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe and Everything.

The class was not what he thought it would be. Rather, “it completely undermined a lot of the assumptions I made about science.” He gives this course credit for opening his eyes to other bodies of knowledge.

“It was a fascinating sort of leveling … because I no longer thought of science as the most important discipline. It made me think, well, all of these disciplines are ways of knowing that are equally important,” Watters said.

As the widespread appreciation for popular astronomers like Neil Degrasse Tyson and Carl Sagan show, Watters isn’t the only one who finds the “story of science” so moving. But for most who tune in to Cosmos as a study break, or pepper their mass transit rides with pages of mainstream science nonfiction, it is largely the universe’s immensity, complexity and infinite capacity to surprise that make these particular scientific stories so spellbinding.

For some, working with and explaining these wonders might take away their mystery. For Watters, it does not. He likens his work to those of other scholars, saying, “If you study a lot of literary theory, and you understand what the author is doing to you, does that interfere with your appreciation of the work? You could say the same thing for landscape or for the night sky, and so on. I think, in general, it enriches my experience of the world. It adds a lot of depth and richness to my experience of sheer life,” Watters said.

“Sheer life” is the phrase just about captures the breadth of Watters’ interests. In college, part of the reason he was able to choose math and physics as his majors was the notion that the things he learned in those pursuits would overlap with some of his other interests, namely art and music, though he admits he has less time to explore them now than he used to.

For him it’s “not just the tools, but also the principles. A lot of the mathematical ideas have applications in both areas as well,” and that “that was certainly something that informed my thinking. By pursuing a career in science, I would learn about all kinds of skills that I could use to explore other areas.”

It wasn’t until Watters was doing postdoctoral work at Cornell University that he encountered the serendipitous turn that would lead him here. There, he met Wellesley Astro alumna Melissa Rice, who knew of an opening in the Astronomy department and recommended Watters for the position.

“She walked into my office one day and she said, ‘There’s an opening at my old department, I think you should apply, I’m writing you a letter.’ It was really nice. And I didn’t have to think about it very long at all. I mean, by the evening, I thought, ‘Wow, this would be fantastic if it worked out,’” Watters said.

Watters has now been at Wellesley for five years. Being in an environment that focuses equally on teaching and research has allowed him to teach thrilling classes like “Hands-on Planetary Exploration.” The course enlists its students in building probes to explore “difficult” environments, requiring that they undertake research and proactively figure out how to print 3D parts and program Raspberry Pi computers in order to drive, fly or launch their projects.

He may love Wellesley, but having spent both his undergraduate and graduate degrees in Boston and Cambridge, he also loves that area. When asked the best spots, he easily rattles off a small alternative guidebook: the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, the MIT Museum, the Brattle Theatre and the Harvard Film Archive. He also recommends the Scientific Instruments Collection at Harvard because not too many seem to know about it.

Asked about how he manages a balance between work and life, Watters describes spending most of his time on his research, exercising and getting adequate amounts of sleep. However, the real heart of his answer is unexpected, although, perhaps it shouldn’t be – not for someone whose ideal dinner party would include the eclectic collection of Mary Shelley, Virginia Woolf, Doris Lessing, Marcel Duchamp, James Joyce and Douglas Adams.

“There’s a convention today, where people try very hard to separate their lives from their work … But there are other ways to think about it. You can mix life and work. And it works out fine, actually, especially if your work is something you’re very passionate about and that you love,” he said.