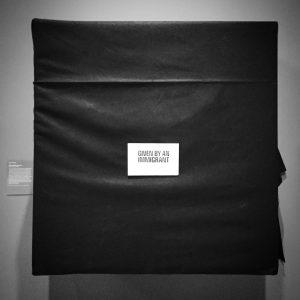

A walk into the Davis Museum at Wellesley College this past weekend might have been more empty than expected, as many exhibits were shrouded or missing entirely. The simple statement that met all visitors was “given by an immigrant.” Accordingly, pieces such as a Thomas Cole landscape, an Ana Mendieta wood-carving and much of the African collection have been made inaccessible to visitors.

On Feb. 16, the Davis announced that on President’s Day weekend, art created or donated by immigrants would be either covered or removed. According to their press release, the Art-less initiative applies to approximately 20 percent of the works in the museum. The Art-less initiative, which is intended to highlight the contributions of immigrants to the Museum, was inspired by President Donald Trump’s recent executive order banning nationals from seven predominantly Muslim countries and the administration’s broader anti- immigrant message.

“Their actions prompted us to reflect on what our collection would look like if the immigrant artists who created work that hangs in our galleries or immigrant donors—many who came to the U.S. as refugees—who gave generously to our collections had not been able to enter the United States” said Claire Whitner, Assistant Director of Curatorial Affairs, who initially proposed the idea.

Various news outlets have covered Art-less at the Davis, including CNN, Hyperallergic and Boston.com. The staff of the Davis who were involved in planning this event did not expect the media coverage that it received, but they “hope that it has prompted dialogue about the critical role immigrants have played in shaping the arts in America,” Whitner said.

Davis Museum Student Advisory Committee (DMSAC) president Caroline Dickensheets ’17 said that “art can be forgotten as a mode of political activism and I think this initiative moves it to the front as a way to protest actions we see as unfair.” DMSAC’s role so far has been to promote the initiative, especially among students. Dickensheets hopes that Art-less will have a role in shaping the museum’s future temporary exhibits and permanent collections.

Citing the example of the museum’s Spring 2015 exhibition of Parviz Tanavoli, widely considered the father of modern Iranian sculpture, Dickensheets said, “I believe this exhibit served as an example of the Davis bringing in non-western art on a large scale that should be continued, especially under the current circumstances.”

“It’s a powerful statement from a community that people usually don’t find political, which I think is valuable,” Bridget Peak ’19 said. “However, the Davis should go further with its activism. There are other aspects that they should address, such as the controversial means by which much art is acquired. They should continue to build upon the steps that they have already taken.”

Peak’s sentiments are reflective of the majority response to the project. While reception to Art-less has been mostly positive, the initiative has still garnered criticism from the community.

In an open letter published on Wellesley Underground, Annie Wang ’14 argued that while the Davis’ protest was well-

intentioned, tangible steps needed to be taken to add more immigrant voices to the collection. Otherwise, she asserted, the gesture was “well-meaning but ultimately empty.” As an immigrant from a non-Western country and an artist with degrees in Art History and Cinema and Media Studies, Wang emphasized that she disagreed with “shrouding the works of immigrant artists,” since she believed that it was neither “the most effective or compassionate way to make a statement” against the travel ban.

At the end of her essay, Wang included a list of three actions that she suggested the Davis commit to in the near future. First, she asked that they “double the amount of work by immigrant artists that will be displayed in the museum’s permanent collection over the next four years,” noting that “Wellesley’s community needs more access to immigrant perspectives, not less.” For this reason, such artwork should be “elevated rather than erased from the narrative.” In addition, Wang cautioned visitors against “seeing immigrants as valuable or important only after being inconvenienced by the void [their] lack of presence leaves behind.”

She added that the Davis should hold lectures that explain the colonialist origins of acquired objects to “restore context” and “dignity to the civilizations they came from.” As an example, she cited the African galleries, which, according to the museum, were shrouded “as a majority of the works -nearly 80 percent – was donated by the Klejman family, who immigrated to the United States from Poland after World War II.” For Wang, the Davis failed to discuss the colonial looting that such objects were subject to before they were gifted to the Klejmans, a process which stripped them “of all context that presents Africa as anything less than a monolith in the popular western imagination.”

Finally, Wang called upon the Davis to place “more women of color and immigrants in positions of leadership,” expressing that their perspectives should inform the future of the museum. She closed her letter by communicating that as the Wellesley community continues to diversify, the “arts institutions should reflect and perpetuate the College’s mission to provide women with an excellent liberal arts education so that they can continue to make a difference in the world…with the added benefit of plenty of exposure to immigrant art.”

With its stand against the travel ban, the Davis has turned art into a creative vehicle for political activism. It is the hopes of students in the greater Wellesley community that the Museum continue with its statement by making tangible steps towards a more inclusive collection of art.