On June 12, 2016, Omar Mateen committed a hate crime in Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. As reported by Ariel Zambelich in their article for NPR titled “3 Hours In Orlando: Piecing Together An Attack And Its Aftermath,” Mateen killed 49 people and wounded another 53, making it the deadliest mass shooting in recent U.S. history.

What mainstream media repeatedly failed to include in the incident’s coverage was that the victims weren’t just gay, they were also queer, trans and people of color. In an interview with “The Atlantic,” Ramón Rivera-Servera, author of “Performing Queer Latinidad: Dance, Sexuality, Politics,” says that on Latin Night, Pulse became a safe-space where hundreds of working class, immigrant Latinx could celebrate their Latinidad and dance their troubles away to reggaeton and bachata.

The media coverage following the incident was largely focused on Islamophobia, homophobia, terrorism and gun control, leaving out the fact that this attack targeted a very specific group of working-class, immigrant, queer Latinx. The lack of discussion about the ethnic/class/immigrant component of this incident from both the mainstream media and the LGBTQIA+ movement demonstrates the crucial need to consider the lives of marginalized groups as a whole with an intersectional point-of-view—the need to dissect the interconnected modes of identities and forms of oppression together, not independently.

Here at Wellesley, the efforts made by students to have multiple identity-based LGBTQIA+ orgs such as Familia and BlackOut have definitely mobilized this process for the administration. Even though Wellesley is a welcoming environment for LGBTQIA+ students, an intersectional approach in administering the diverse LGBTQ+ life at Wellesley is crucial, for there are ethnic-specific, class-specific and gender-specific ways to help LGBTQIA+ students navigate life at Wellesley.

As Kimberlé Crenshaw elaborates it in her article “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Anti-discrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” modes of identification and the systematic oppression, injustice and inequality they carry do not act independently of one another and instead interrelate, creating a system of oppression that reflects the intersection of multiple forms of discrimination.

The theory of intersectionality was first coined by Crenshaw, critical race theorist, lawyer and civil rights advocate based on the racism and classism that plagued the feminist movement since the first wave of feminism as explained in the article “‘Ain’t I a Woman?’: Revisiting Intersectionality by Avtar Brah and Ann Phoenix.”

Mainstream feminism has largely been focused on the oppression experienced by cis, white, middle-class women, maintaining the idea that all women share the same life experiences and prejudices, but oppression is identity-specific. Intersectionality hopes to reject a hierarchy of oppressions and achieve equality through difference.

In their book, “Communicating Gender Diversity: A Critical Approach,” Victoria Defrancisco and Catherine Palczewski elaborated on Crenshaw’s argument, stating that for Black women the intersectionality experience is “more powerful than the sum of their race and sex” and that any observation that does not take into account the interconnections cannot accurately address the way in which these women are subordinated. With the efforts made by Black feminists, intersectional theory can be and has been applied to combating and understanding all forms of systematic oppression.

As Horacio N. Roque Ramirez investigates in his article, “Gay Latino Histories/Dying to Be Remembered,” history privileges the stories of white middle-class bodies. When the mainstream media and LGBTQIA+ community co-opted the shooting and stripped it of its Latinidad, they erased the stories of these struggling working-class immigrants, and continued the historic “othering” queer Latinx face in the U.S. by both U.S. mainstream white LGBTQIA+ culture and by their heteronormative Latin cultures.

When the Spanish surnames of the victims were announced, this shooting became a Queer Latinx point of discussion, allowing us to speak of the ethnic-specific and class-specific issues that queer Latinx face in this country. Racism and xenophobia are present in both the queer community and out. Homophobia and heteronormativity are present in Latin cultures as well as others, and in order to combat against these oppressive forces, Latinx must fully understand how and why the oppressive forces Latinx face work the way that they do.

Wellesley has often been called upon to speak for the wider LGBTQIA+ umbrella. Our administrators and the LGBTQIA+ community at Wellesley are overwhelmingly white, cis-gender, able-bodied men and women. While they may not be discriminating against anyone, it is problematic that they are representative of only one aspect of the Wellesley community.

Given the popular portrayals of the LGBTQIA+ community as white, it is obvious why the appropriate actions needed to provide a welcoming community to LGBTQIA+ minorities at Wellesley might be neglected or not rightfully fulfilled.

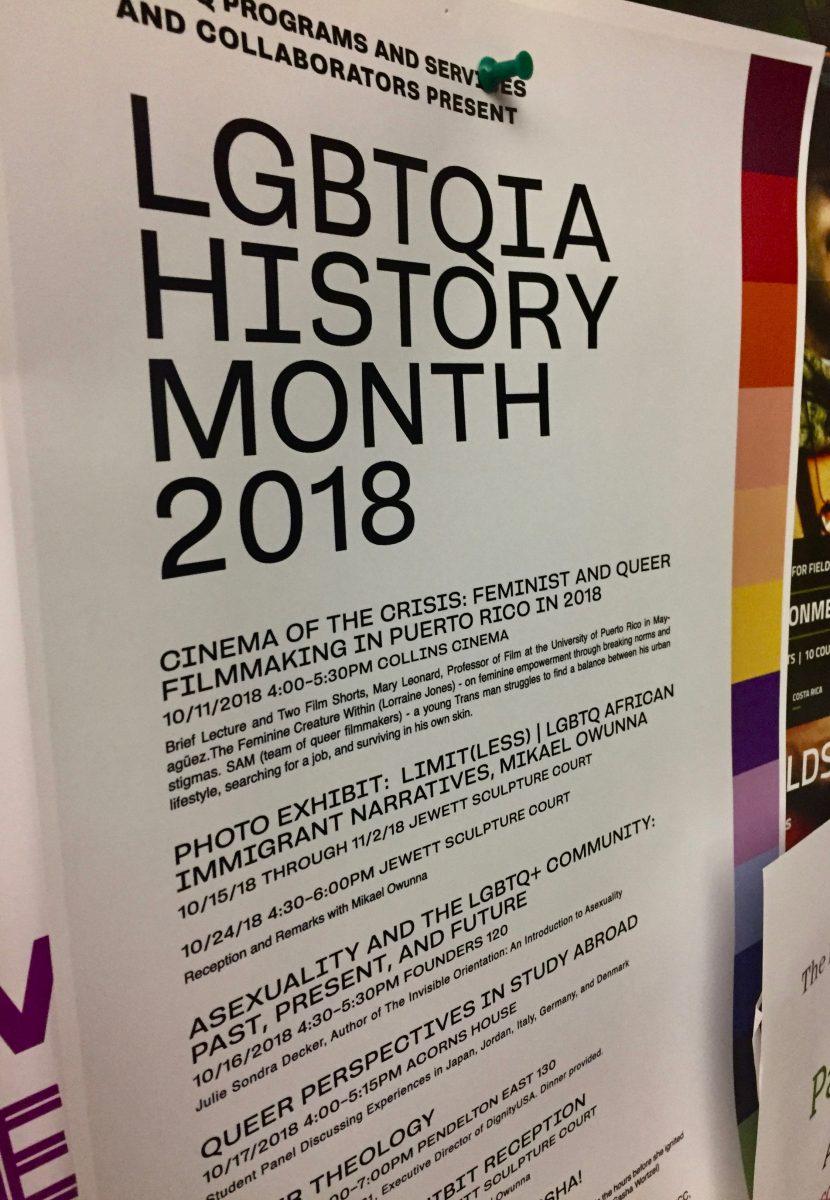

One way of applying an intersectional approach is through Queer Council Advisory Board’s role at Wellesley (QCAB). QCAB was created in order to serve as a liaison between the multiple LGBTQIA+ groups on campus and the Assistant Dean of OICE and LGBTQ Programs & Services. QCAB helps us to ensure that we are not overlooking the challenges of people belonging to multiple minorities, which means continuing the moves we have made but also improving upon them we move toward the goal of a fairer campus and society.