Louise Glück speaks the way she writes: with an unapologetic boldness. “To compose poems, I wait and I listen,” she explains. “Not to the world, but I wait for a sound that doesn’t sound like the old sounds. I wait for a new world, one that I can explore. I like to go on a long voyage.” Each word is carefully chosen, a testament to the masterful precision of her language. Her poems are succinct, exposing the most intimate aspects of human thought with astonishing accuracy. “I just plow forward,” she admits. “I continue drawing breath and I hope.”

At 73, Ms. Glück’s tremendous career spans 16 books of poetry and boasts an array of awards, including the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the 2001 Bollingen Prize. Hailed in literary circles for her technical skill and insightful empathy, she is widely regarded as the most accomplished contemporary poet. This fame is of little consequence to Ms. Glück though. “I don’t look backward, rubbing my stomach contentedly and appreciating the monument. I think obsessively about what I hope for the future,” she says.

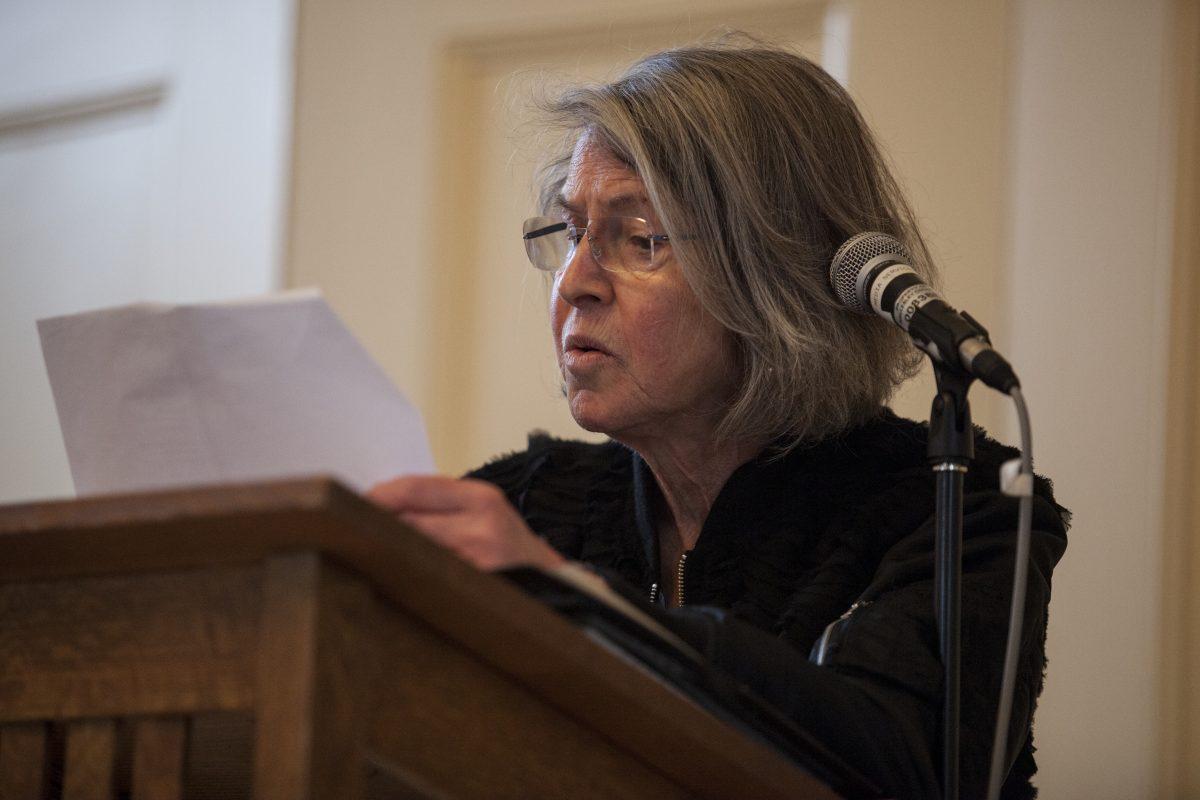

When I called Ms. Glück on a rainy Thursday morning, she was fresh from a reading at Wellesley the night before. She had selected works from her previous books, skipping over those that least lend themselves to being excerpted. Pulling her poems into a cohesive unit is a technique in itself. As she describes it, “it’s like tracking prey in the forest. You don’t analyze it and then figure it out. You sniff it out.”

For Glück, whose poetry tackles difficult topics such as anorexia, divorce and loneliness, the experience of writing is never cathartic. Instead, she considers these hardships easiest to discuss since all the information she needs is already present in her mind. The process “is not a sort of volcanic purification of the self,” she explains. “Not a vanishing from the self of these evil spirits. It’s more trying always to make experience mean something, to signify some importance and weight and value.” Composition is the ability to turn suffering into an advantage.

Glück is also notable for her incorporation of mythological narratives. Averno, for instance, explores the seizure of Persephone and her subsequent trip to the underworld. Glück reopens the canonical story by questioning the intentions of the characters. In a way, she humanizes the divine. Though her proclivity to these figures is natural, given that she was exposed to them as a child, she admits that using them could be a mistake: “I think it tends to look as though I’m propping up my trivial poem with grand references, as though to sort of endow that foolish little poem with a dimension and weight and gravity that it hasn’t really discovered on its own.”

However, she acknowledges that every now and then, the classics are the only way to examine something. Using Persephone, for example, is a way in which to contextualize her relationship with her mother. “I much more identify inwardly as a daughter than as a mother. I am both, but the daughter experience was more forming. Actually, it was pretty horrible but it stayed with me.” For her, poetry is a way of discovering the self, and as Ms. Glück insists, she wants to be discovering again.

As she continues to write, Ms. Glück has no reservations about the perpetuation of the art form. Poetry is flourishing. The medium has lasted for centuries of human history. She claims, “people who love the form, love it. They love it desperately. That’s an extraordinary thing.” Poetry, she notes, is a craft that will survive darkness, because it is made for darkness.

With her talents focused on composing another book, Ms. Glück is prepared for a restoration of her inventive capacity. There is no reliable mechanism by means of which this will happen, but the experience is transcendent. As she puts it, “I feel as though I’m being dragged forward by some force I can’t seek out actively or identify.”