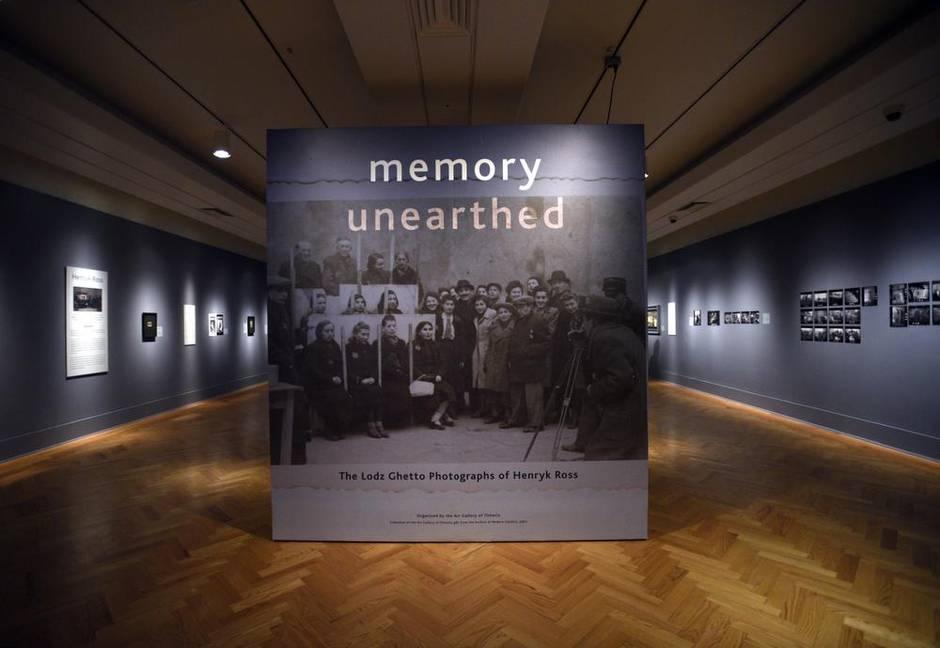

I stumbled onto the Boston Museum of Fine Arts’s contemporary exhibit, “Memory Unearthed,” completely by accident. I had gone with a friend to the museum to fulfill the terms of an assignment with the aim of seeing another artist’s work. My friend, who is not a Wellesley student and who graduated last semester, resisted my dutiful impulse to see the installation I had originally planned to analyze, and instead dragged me across an upstairs hallway into this photographic testament to the lives and suffering of Polish Jews under the Nazi regime. My experience of the art was changed by the fact that it was shared.

Henryk Ross (1910-1991) was a Polish Jew who, along with thousands of others, was rounded up and forced to live in the Jewish ghetto in Lodz, Poland. As a photographer, he was employed by the Nazi-controlled Jewish council (the Judenrat) to officially document the members of the ghetto, both living and dead. His duties included taking photographs for Jewish ID papers, cataloguing unidentified corpses and participating in the production of propaganda through the documentation of Jewish forced-labor initiatives. Unofficially and at enormous personal risk to himself and his family, Ross surreptitiously documented not only the Nazi atrocities within the ghetto, but also the daily lives of its inhabitants, managing to capture moments of life and joy alongside terrible suffering. Before Ross was transported to Auschwitz around 1944, he managed to hide all of his photo negatives in iron-lined jars, which he buried and later dug up when he was rescued at the end of the war. The wall text in the exhibit explained his reasoning in his own words: he wanted an “historical record of our [i.e. the Jewish] martyrdom.” And indeed, that is what the exhibit accomplishes.

In the exhibit, there are images of mass suffering: countless photos of corpses, of mothers being loaded into carts with their children to be transported to their deaths, of of starvation and of forced labor. I saw old women talking through a fence, their faces wrinkled in concern. On one side of the fence was life, and on the other, death, but the wall text did not indicate which was which. Amongst these images, and in an order chosen by Ross, there are pictures of families, portraits of young people and images of celebrations. A young woman looks in a mirror. One figure helps a man stand up after he has collapsed in the street. The pictures are neither sensitized nor sensationalized; they are meant to be viewed side-by-side, a testament to the precarious existence of Lodz’ Jewish community. In many Holocaust narratives, there is a feeling of distance, both a sense that this could never happen here and a sort of dehumanizing force created by the sheer volume of the dead, whose silenced voices cannot speak for themselves. In Ross’ photography, his subjects speak. They are individuals. Their suffering does not take away from their humanity; it outrages ours, as well it should. Ross’ talent as a portrait photographer shines in his ability to capture the spirit of the people he depicts. Most heart-wrenchingly, his own voice speaks through the lens of his camera, mourning on behalf of the lives of people he could only watch, but not save.

This exhibit is particularly relevant, as I suspect the MFA curators intended, in light of the staggering injustice and dangerous public policy that plagues our country and our world. The crushing mechanisms of oppression pay no heed to individuals. But we, the people, the individuals, we watch them. We document their offenses, and we bear witness, and that is our power. After the war, Ross’ photographs and his testimony led to the conviction of Adolf Eichmann, one of the masterminds behind the Holocaust. In comparison to the millions of lives Eichmann’s actions had helped to end, it was a bitter sort of justice. Nonetheless, it was a concrete effect of Ross’ artistic and personal bravery, one that is easy to quantify. More difficult to describe is the human impact of this witness. It is never enough to say that someone’s death was not in vain because we keep them in our memories. I don’t know the people in Ross’ photographs, and I never will, because they were senselessly murdered by a corrupt and evil political regime before I was born. Likewise, most of the people viewing the exhibit with me would never have had a chance to know these people — and yet we feel their loss as we witness their individuality and personhood. Their suffering, relentlessly captured through the agonizing efforts of one man, is engraved on our collective consciousness. Will that be enough?