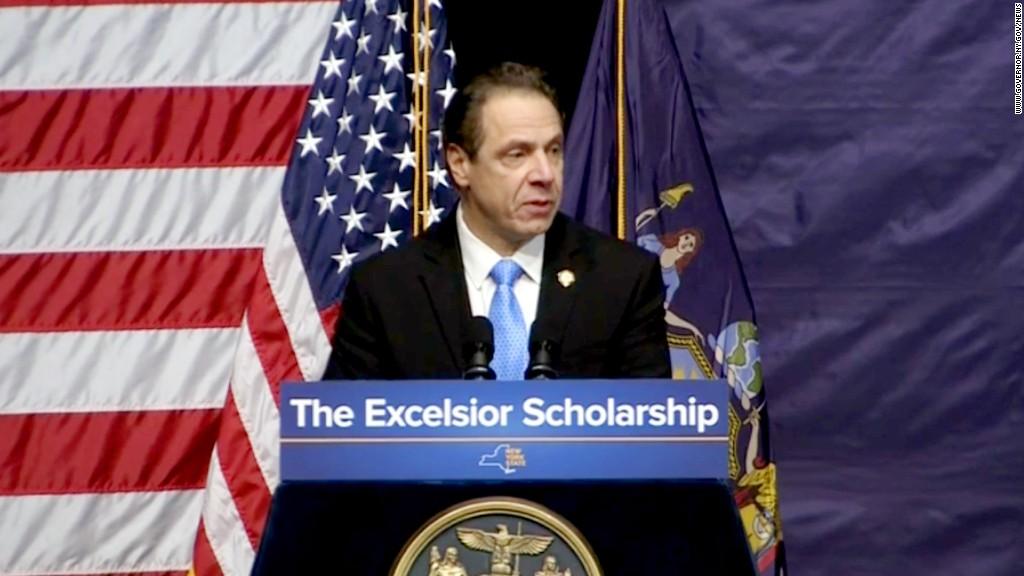

This year, New York State introduced its Excelsior Scholarship, granting free tuition to state universities for families making $100,000 or less. Lawmakers, such as New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, praised the initiative for being the first to offer free tuition to in state universities. While the Excelsior scholarship seems to be a near-perfect piece of legislation, upon closer investigation, the scholarship has a multitude of flaws that could ultimately hinder the population it claims to serve. What students need are scholarships without strict obligations and the chance for upward mobility after graduation. Sadly, the Excelsior scholarship offers neither of these things.

The first problem with the Excelsior scholarship is that it can be revoked any point while a student is completing their degree. The scholarship requires full-time enrollment and a grade point average “required to complete the necessary coursework.” While these requirements are ostensibly set to encourage participants to complete their degree on time, these requirements do not consider some of the external situations that students face. The Excelsior scholarship makes college more affordable, but not free for students. Tuition is currently $6,470 at four-year universities for Excelsior recipients. Without support, it is incredibly hard for young students to pay this tuition, which doesn’t include the cost of textbooks or living expenses. According to the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, 70 percent of college students work part time while completing their degree. Twenty five percent of students work full time while enrolled at school full time. The reality is that college is expensive and the costs need to be financed in addition to any financial aid. If students cannot afford the reduced tuition and extraneous costs not covered by the Excelsior Scholarship, should they be expected to work and be enrolled full time in school as well? Since the Excelsior Scholarship claims to serve families that are middle class and below, it should make the requirements more accommodating to these families and students.

The scholarship also requires that recipients reside in New York post-graduation for the amount of time it takes for completion of their degree. The scholarship does not require recipients to be employed in New York for the duration of this time, but recipients may not be employed in another state. This requirement is so that New York retains the graduates that it funded, however, this is the wrong method of doing so. If a recipient fails to meet this post-graduation requirement, the Excelsior Scholarship is no longer a scholarship, but a loan that recipients are then forced to pay back to the state. Instead of forcing recipients to reside in New York, perhaps the state should invent desirable incentives for graduates to remain. This requirement is probably the most unfair because it does not promote mobility for students. Oftentimes students are recruited to work in other states after graduation and may be forced to turn down a potentially high-paying job to meet the resident requirement.

Although this initiative is the first of its kind, the Excelsior Scholarship needs to stop flaunting this accomplishment. Private institutions such as Wellesley have spent years making college more affordable for students who need it, although not without fault. The sheer fact that the Excelsior Scholarship can turn into a loan is a ridiculous policy that helps no one but the state. If New York wants to help students affordably go to college, they should have more flexible requirements and help recipients find competitive employment that helps them remain in-state. While I applaud New York for making this first step, we must realize it is but a small step in a long marathon of making college affordable for those who deserve it.