After six years, 125 global artists and around 62,450 frames, Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman’s product, “Loving Vincent” is worth every brushstroke. The world’s first fully oil-painted feature film is a complex cinematic narrative that not only brings Van Gogh’s portraits and landscapes to life, but also works to destigmatize the mental illness that takes the forefront of most narratives of Van Gogh’s life story and turned him into perhaps the most iconic representative of the tortured artist archetype.

It’s important to note that “Loving Vincent” is essentially an animated museum—a moving exhibition focused on using Van Gogh’s paintings and letters to question Van Gogh’s supposed suicide, rather than a documentary that gives a blow-by-blow of Van Gogh’s misery. The film addresses the legends around the artist’s suicide in a more diaristic form, using Van Gogh’s letters as a foundation. It also gives a fictionalized murder mystery narrative involving young Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth) who wishes to find the proper recipient for the last letter Van Gogh had written for his soon-deceased brother.

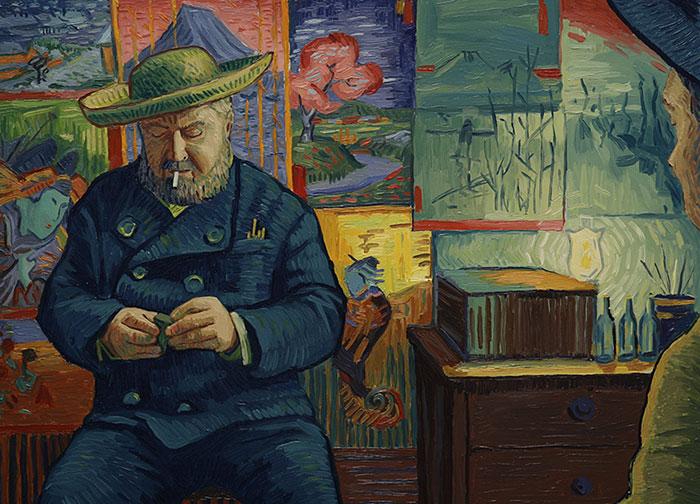

Through interviews with characters from portraits Van Gogh painted in real life, the film crafts a Poirot-like crime story that traces and maps the differing stories of villagers to uncover the “true” happenings that led to Vincent’s death, as well as the type of man he was—quiet, humble and lonely with a warm heart and curious soul. The film uses family history, friendships and village acquaintances enlighten viewers on the roots of Vincent’s depression, his love for his brother Theo and his relationships with the people he painted that truly recognized his talent, such as Dr. Gachet (Jerome Flynn) and Père Tanguy (John Sessions).

Rendered off of Van Gogh’s own idiosyncratic modernist style, the film’s paintings bring its characters to life, embodying Van Gogh’s dedication to expressing man and nature’s inner spirituality. As the textured and gestural brushstrokes depict the psychological dynamism of Van Gogh’s own life, so do they also express the emotions and perspectives of the various characters, transforming two-dimensional artwork into a psychedelic story that breaks the traditional boundaries of film animation. Past and present are strictly distinguished by transitioning from paintings that resemble his smoother and more traditional early works to those possessing the rhythmic and vivid chaos of his iconic later works.

The film seeks to do with its paintings what Van Gogh sought to accomplish with his: to “touch people with [his] art” and to show the depth and tenderness of his feelings. By looking at his life via flashbacks of those who knew him and lacing the film with narration of personal letters, “Loving Vincent” presents a deeper and more complex picture of Van Gogh as a human being that goes past “that artist that chopped off his ear.” Viewers can marvel at the beauty of each and every frame, but they can also enjoy a cinematic experience that reverses the typical portayal of the artist’s self-destruction, instead using Van Gogh’s tradition-altering work as a means to appreciate his life and struggles.