“THE DONOR OF TOWER COURT MADE KNOWN,” proclaimed the front-page story of the June 21, 1917 issue of The Wellesley News. The piece goes on to describe a ceremony, following the 1917 Commencement exercises, in which a memorial tablet bearing the name of Ellen Stebbins James (1833-1916) was placed above the fireplace in the Great Hall of the newly-built Tower Court.

Stebbins, who died a year before the dedication ceremony, was neither an alumna nor a member of the College’s faculty. Rather, it appears she was simply a humanitarian who took a special interest in Wellesley College and provided two large anonymous donations to Wellesley, including one after the 1914 College Hall fire for the construction of a new dormitory—which would become Tower Court.

“It has ever been my hope that this beautiful building would stand as a monument to her character, strong enough to defy the ravages of the years, complete in every detail; rich in design, yet full of grateful simplicity, it exists, as did she, ever ready to minister to the needs of all who come within its shelter and need its protecting warmth and cheer,” expressed a close friend and representative of James in a speech at the ceremony.

However, Tower Court’s name makes no reference to James, or to anyone, for that matter. What about the numerous buildings on campus with names that do? Surely, those that bear the surnames of alumnae, faculty and benefactors are even more overt monuments to these people and their memories. What exactly goes into the naming of a building at Wellesley? Historically, it seems that no particular protocol has existed, but rather that building names have been dictated by various factors over the years.

Construction on Bates and Freeman Halls was completed in 1952. At the time, the new dormitories met a pressing need for additional on-campus housing for Wellesley students. The construction project was carried out with careful consideration of functionality and modernism, but also with attention to Wellesley’s history and identity.

The chairman of the Board of Trustees, the Reverend Dr. Palfrey Perkins, announced in the buildings’ September 1952 dedication ceremony that the two halls had been named in memory of Alice Freeman Palmer (1855-1902), president of Wellesley College from 1881 to 1887 and a national advocate for women’s education, and Katharine Lee Bates (1859-1929), class of 1880, professor of English literature for many decades and the poet who authored “America the Beautiful.”

An article in The Wellesley Alumnae Magazine from November 1952 includes an excerpt from Perkins’ speech at the ceremony: “The Board of Trustees found that the choice of names was no more carefree and easy a task than it is sometimes for the parents of a new baby. During the past few months, many suggestions have been made from many quarters. The wisest method seemed to be to submit the list of suggestions in referendum to the trustees, who expressed their choice in order of preference, with many deliberately not considering the names of living persons. . . .Two names led all the rest. They are the names of two women who in their lifetime gave Wellesley faithful service, and to whom the college owes a great debt.”

A less meditative process took place in the naming of Green Hall, officially called the Hetty H.R. Green Hall. Though plans for the administrative building were drafted in 1918, construction did not take place until 1931.

Green Hall was financed by Hetty Sylvia Ann Howland Green Wilks and Edward Howland Robinson Green, in memory of their mother, Hetty Howland Robinson Green. Hetty Green (1834-1916) was an iconic Gilded Age investment banker who was once considered the richest woman in America. Nicknamed the “Witch of Wall Street,” she was also famous for her miserliness.

Though Green had no connection to Wellesley, after her death her children donated her fortune to various institutions across the United States. According to the Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey of Wellesley College Buildings and Grounds, their donation agreement with Wellesley College was such that “each would contribute $50,000 per year for five years if the College would construct a building to be known as the Hetty H.R. Green Hall.”

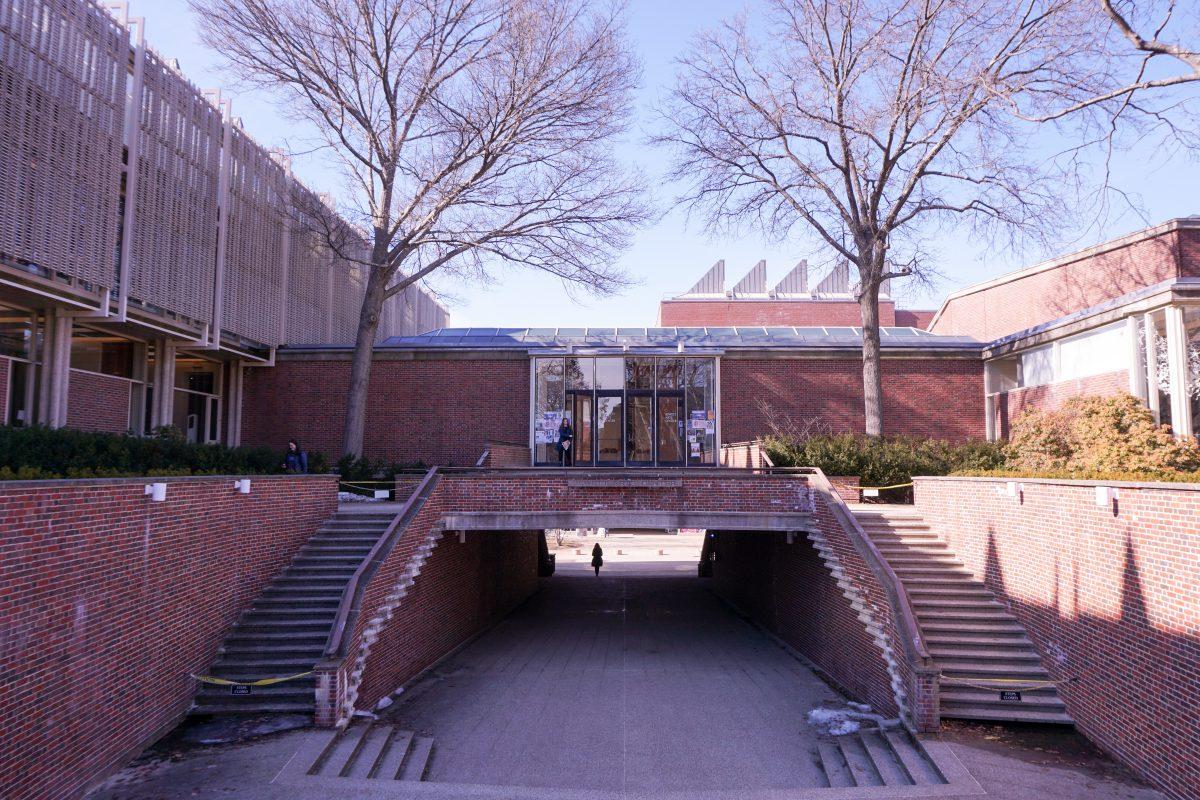

Wellesley’s Jewett Arts Center was also named for its primary benefactors. Made possible by a gift from Mary Cooper Jewett and George Frederick Jewett, Sr., who had close ties to Wellesley, the building met a long-standing need for an arts center to replace the Farnsworth Art Building, which lacked enough space and facilities for Wellesley’s growing arts program.

Initial proposals had been for an expansion of the Farnsworth, but those eventually evolved into plans for an entirely new structure. The Farnsworth, which opened in 1889, had its own eponymous significance. According to Martha McNamara, director of the New England arts and architecture program at Wellesley College, the building had been named for Isaac Danforth Farnsworth, a childhood friend of Wellesley College founder Henry Fowle Durant.

“It is probably the case that some people were against the destruction of Farnsworth, but the Art Department was adamant that a new building — not an addition to Farnsworth — was needed,” said McNamara.

The Jewett Arts Center was completed in 1958 and is actually named for two members of the Jewett family: the art wing for Mary Cooper Jewett ’23, a Wellesley College Trustee, and the music wing named for George Frederick Jewett, Sr.’s mother, Margaret Weyerhaeuser Jewett, who attended Wellesley from 1882 to 1885.

Today, as in the past, protocol for dedicating buildings on campus is not strictly outlined. Committees seem largely to be formed ad hoc, and processes vary between projects. In financing these projects, though, the College takes careful steps to preserve Wellesley’s historical choices and patrons and also to recognize contemporary donors.

Bridget O’Connor Garsh ’04, senior director of marketing and donor relations at Wellesley, explained, “In most cases, the College identifies giving opportunities that donors can support and determines whether the donor’s name will be included during the planning phase of a building project.”

Donors who supported specific giving opportunities during the recent renovation of Pendleton West, for instance, were able to name the spaces they supported, but the overall building name honoring Ellen Fitz Pendleton, a past president of the College, remained the same.

Garsh also noted that the wishes of donors who are granted naming rights vary. “Some prefer to have their name used for a particular space while others may choose to honor someone meaningful in their lives, and others may choose something entirely different,” she said.