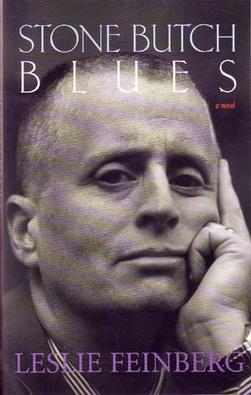

Note: Leslie Feinberg used both she/her and zie/hir pronouns over the course of hir life. This article follows the style of Feinberg’s literary executor and uses both sets of pronouns.

The online 20th Anniversary Edition of the late Leslie Feinberg’s 1993 novel “Stone Butch Blues” includes a lengthy author’s note. It contains, among other things, Feinberg’s explanation about the long process zie went through to recover author’s rights, hir intentions to keep the novel available for free and a blanket response to requests for permission to make adaptations or derivative works. That response reads, in part: “No permissions, no contracts, no commercial use, no derivative use, no digital rights…No adaptations: don’t tell me you’re honoring me by saying you can tell this story better than I did.” She goes on to specify that she does not give permission for film adaptations, writing, “I don’t believe any movie can be made true to the intention of the book.”

However, an independent studio called 11B Productions is planning on adapting “Stone Butch Blues” anyway. A casting call was recently placed on Backstage.com for the role of the main character, and 11B Productions has listed the film on its website, with no information other than “coming soon.” The casting call has raised difficult questions about the nature of intellectual property, about respect for the legacies of artists and about how, if at all, a film adaptation of this novel could be successful.

“Stone Butch Blues,” a semi-autobiographical novel about a butch named Jess Goldberg who comes of age in the 1960s and has a complex relationship with gender, still holds great importance in the literary world, in the lesbian community and in the LGBTQ community as a whole 20 years after the novel’s publication and four years after Feinberg’s death. Among the many powerful aspects of the novel is its willingness and ability to talk about the complexities of gender, particularly for butch lesbians.

It’s also an incredibly heavy novel, dealing with rape and police brutality. As Feinberg wrote in the author’s note, “I worked briefly on a movie version of ‘Stone Butch Blues’ until I discovered that the producer’s prospectus was trying to raise capital from investors by offering a sexual fantasy: an invitation to watch butches being raped by police. I requested that no movie be made.”

Slate, an online publication that covers culture, and a few online commenters have speculated that the soon-to-be-film stemmed from this past, abandoned project. But we don’t know enough about the circumstances that led to the casting call to know whether or not the current project is legal. However, assuming that it is, this is still disrespectful to the author’s legacy.

Feinberg is hardly the only author to request that no film adaptation be made of hir work. J.D. Salinger was famously, vehemently, against any film adaptation of “Catcher in the Rye” and Gabriel García Márquez only wanted a film of “One Hundred Years in Solitude” under very specific — and nearly impossible — conditions: two minutes of film would be released each year for 100 years. Two core ideas often motivate authors to retain film rights for their novels: distrust of the film industry, as in Salinger’s case, when Hollywood’s mishandling of an earlier work of his led to him swearing off it forever, and the belief that some stories are better told the way they are. Feinberg notes both of these beliefs in hir author’s note. At the end of the day, however, it can be seen as worrisome when an author’s work is co-opted after their death, no matter the reason. Feinberg’s work is hers, and she requested it be kept solely in novel form to preserve her vision. Going against hir wishes after hir death, especially for such a historically important piece of work by a marginalized creator, feels disrespectful.

There’s also the issue of Hollywood mishandling LGBTQ stories. “I’d like to think that a successful, respectful and sensitive film could be made of ‘Stone Butch Blues,’” Wellesley College professor of American studies Paul Fisher said over email. “But the question in the abstract is different from the actual practice of the film industry, which doesn’t have a great track record, especially in representing trans stories and characters.” The fact that the filmmakers want to cast a transgender actor as Jess is at least a step in the right direction, considering how many Hollywood movies cast cisgender actors to play trans characters, most recently in films like “The Danish Girl” (starring Eddie Redmayne) and “Anything” (starring Matt Bomer).

Yet doing so is problematic in its own way. While Jess is definitely on the trans spectrum, the entire novel is about how complex their gender is. The casting call specifically calls for actors who are trans men and transmasculine nonbinary people and does not mention butch lesbians. This is in spite of the fact that many butch lesbians have journeys similar to Jess’, including going on hormones, getting top surgery and even transitioning, and then detransitioning. The fact that butch lesbians are excluded from the casting call could suggest a better-than-average understanding of issues of trans representation in Hollywood, but it could also suggest a flattening of Jess’ gender identity.

The fact that the role only calls for Caucasian actors is also an issue. It isn’t whitewashing per se: while Jess is Jewish, their race is left ambiguous. However, this ambiguity is important in the novel, as Feinberg writes: “For derivative artists, intent on making derivative art using a narrative I have written, this means that they take their individual idea of who is Black or white, fat or thin, able-bodied or disabled— and the derivative artist flattens and concretizes their own interpretation for all time, as if that’s the truth of ‘Stone Butch Blues’ for all time and all readers.” Insisting that Jess must be white also oversimplifies their character and tells a particular story – one that is less ambiguous and less complex than that in the novel.

Regardless of what happens with the film, “Stone Butch Blues” will always be an important novel. “Leslie Feinberg’s books have done a lot for trans liberation, and it would be great if a film could continue that work,” said Fisher, “but that’s a tall order.” He added, “Whether or not a film gets made, everybody should read the book — and they should read it before seeing the movie!”