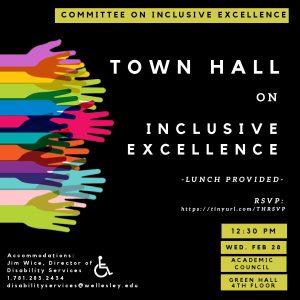

On Wednesday, March 28, the Committee on Inclusive Excellence held the first of its series of town hall meetings to take on the issue of making academic achievement at Wellesley more accessible to students of marginalized backgrounds. The committee, which is comprised of students, professors and administrators, called the town hall a “first step.” Participating community members gathered in the Academic Council Room to discuss how this institution perpetuates what is sometimes called the “achievement gap”—the fact that, at Wellesley and many other elite institutions, students of color, low-income students and first-generation students who enter the institution just as qualified as their white, wealthier counterparts end up with lower grades than would statistically be expected.

The town hall was designed as an open forum for students to voice the ways they have experienced discrimination at this institution as well as the ways in which Wellesley has failed to support them.

“The idea is really to open up the conversation about what inclusive excellence should look like at Wellesley because a lot of the current academic practices really aren’t inclusive and disproportionately affect students from marginalized backgrounds, students from low-income backgrounds, students who are first-gen and students of color,” said Dina Al-Zu’bi ’19, who, along with Caitlyn Chung ’20 and Kamaria DeRamus ’18, is a student representative on the committee. At the town hall, the normal setup one would see in a classroom was reversed: here, the students were the ones speaking, while all professors in the room were asked to remain silent and listen to understand instead of listening to respond. The room was packed, with many students, professors, and staff members sitting on the floor when chairs ran out.

“It’s to give students an ease of mind,” explained Chung. The town hall “isn’t a place of discourse or retaliation on the students, and it’s not a place where we’re trying to leverage power differences. Because there is a big power difference between students and professors. It’s a place where we wanted students to be able to freely voice their opinions, voice their experiences, without having that limitation of worrying what my professors will think, worrying what will come as a backlash immediately after. So we’re trying to mitigate emotional response, in a sense,” she continued.

The town hall was a place for students to speak to their own experiences, Al Zu’bi said. Those experiences, for students of color, first-gen students and low-income students, are often much more difficult than those of others, especially during their first few semesters at Wellesley, as many students articulated during the town hall.

“If you are taking a class that has a lot of p-sets [problem sets] like computer science or neuroscience or economics and you have to spend at least 10 hours on a p-set, while also working a job or managing three workstudy [jobs], it’s very clear to see how that would disproportionately affect students of low-income backgrounds or first-gen students as opposed to students who have the privilege of not having to work on top of that,” Al Zubi explained. “Also, another example that comes to mind is when issues that are political happen in the world or in the U.S. and have students of color exerting tremendous amounts of energy and emotional labor not only processing the trauma and dealing with it but also organizing actions and responses on campus. All of that is time spent outside of the classroom focusing on things that aren’t academics,” they added.

Chung also noted that, while some professors are supportive and understanding, others are decidedly less so.

“I think if we’re going into the nuances of emotional labor, there’s in-classroom discussions as well,” she said. “A lot of professors who do not embody whatever’s happening right now in the political sphere—they sometimes unknowingly or sometimes knowingly push this emotional labor onto students of color within their classrooms. So they ask their opinions, they ask what’s happening and they sometimes tread upon things that they shouldn’t. And I think that an issue of putting responsibility on the students that they didn’t ask for and they weren’t willing to take on beforehand.”

At the town hall, the facilitators asked two different questions, with response periods of 35 minutes each. First, they asked the students in attendance how they perceive their own backgrounds and identities as affecting their experiences here. Then, they asked students what faculty members have done, and what faculty could do in the future, to improve student experiences.

Students praised the efforts of some professors to get to know them well, while also noting that other professors didn’t seem willing to account for the experiences of marginalized students in their classrooms.

Professor Yu Jin Ko, chair of the Committee on Inclusive Excellence, believes that the conversation allowed professors to see a side of the student experience that they normally would not. “The faculty that I’ve spoken with are thinking of this as a first step in a longer conversation, that will eventually lead to thinking about solutions to many of the concerns or the challenges that students talked about.”

Many students brought up a desire for more faculty of color in our classrooms. Dominique Lafontant ’19 said that there is an expectation for students of color to advocate for themselves and that professors often don’t step up to advocate instead.

“Stop forming committees and start enacting policies,” said Anjali Benjamin-Webb ’18. “We expect more.” (The full text of what BenjaminWebb said at the town hall is published in our opinions section this week.)

Ko says that this town hall has made some things that this school needs very clear.

“A number of first-gen students, for example, talked about how unfamiliar they were with even the concept of office hours,” Ko said. He believes that this, along with the lack of faculty members of color, is something that the institution can work to fix. “So Dean Velenchik is rethinking how we do first-year orientation. I’m sure she’d be very happy to make giving information about office hours to students part of orientation.”

The town hall was, as Chung put it, designed to be “a space where students would feel comfortable saying things that are uncomfortable, and that professors might not want to hear.” Ko said that, while the things students said about their treatment here at Wellesley may have shocked some professors, they were things that professors needed to hear.

“I’ve heard from a number of faculty, for whom it was a culture shock. They didn’t realize the extent of the pain that a lot of students felt. They also were unaware of the anger that a lot of students felt. So I think it was very instructive, it was eye-opening.” While professors at the meeting were not allowed to speak, it was deeply instructive for those faculty members who attended. In addition, according to Ko, there are activities, panels, and even a retreat planned for faculty to teach them about inclusive pedagogy.

The next town hall, at which both faculty and students will be speaking, is scheduled for March 13 at 4:15 p.m.