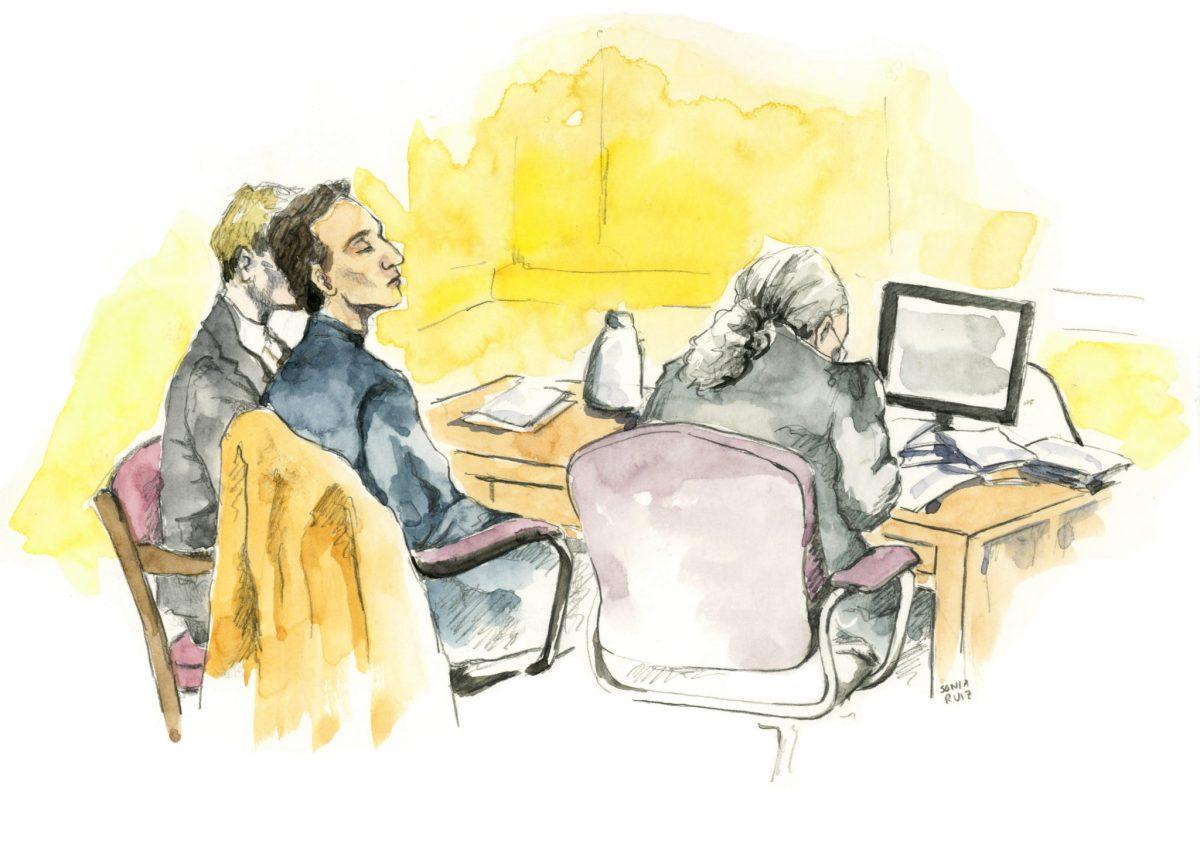

On Feb. 26, Saifullah Kahn, a former cognitive science student at Yale University, sat in a New Haven courtroom and listened to his alleged victim’s emotional testimony. Jane Doe, the pseudonym given to the alleged victim in court documents, accused Kahn of raping her after the 2015 Yale Symphony Orchestra Halloween Show. Doe reported the alleged abuse to law enforcement the following day, and Kahn was arrested and suspended from Yale that November.

Yale is one of the many universities that employs its own police department. Though the Yale Police Department carried out much of the investigation against Kahn and arrested him in November of 2015, the Connecticut state attorney’s office was responsible for prosecuting the case in a court of law. Kahn’s original trial was set for the fall of 2017. However, the judge declared a mistrial after the Yale Police Department introduced pieces of evidence from its investigation that were never made available to the defense. Kahn’s attorneys are now arguing that Yale University’s bias against their client is interfering with his constitutional right to a fair trial.

Kahn’s case has re-ignited the controversial debate over what role colleges and universities should play in handling sexual assault cases that occur on their campuses. Samantha Harris, the vice president for Individual Rights in Education, feels that Kahn’s case exemplifies why colleges and universities should leave sexual assault investigations up to police departments that are not affiliated with their school. “It seems like kind of the worst-case scenario, where the university’s processes may have affected the ability of the criminal justice system to function properly,” Harris told The New York Times.

I agree that if a student chooses to report a case of sexual assault to law enforcement, the investigation should be handled by a police department independent of the college or university to ensure that both parties get a fair and unbiased trial. However, colleges and universities should continue to be held accountable for ensuring the emotional and physical well-being of their students in the aftermath of sexual assault.

Kahn’s defense team is arguing that the Yale Police Department’s investigative role in this case is preventing him from receiving a fair trial. I cannot speak to the agenda of the Yale Police Department, if they have one at all, but previous cases of sexual assault that took place on college campuses show that affiliated police departments are capable of letting biases impede their investigation. However, in most cases these biases harm the victim far more than the accused.

One example is the story of Erica Kinsman, who was a student at Florida State University, where she was sexually assaulted. She immediately went to her campus police department and had a rape kit exam done at a nearby hospital. The police identified her alleged rapist as football star Jameis Winston but closed the case without questioning the accused or any other key witnesses.

Ultimately, colleges and universities are businesses with high stakes in these cases. While there are schools that are willing to do the right thing and take reports of sexual assault seriously, others are willing to brush these cases under the rug to protect the names of certain students, as well as their institution’s, names. Though independent police forces certainly do not have spotless records in dealing with sexual assault cases, leaving the legal investigations to them might help to eliminate some of the biases.

While I believe that sexual assault cases should be investigated by independent police departments, I recognize that colleges and universities can provide survivors with accommodations and resources that the justice system cannot. For example, college administrators can make students feel safer on campus by providing them with access to therapy or allowing them to switch rooms if they are currently living near the site of the attack. Administrators can also aid survivors’ academic success by contacting professors to excuse them from missing class or turning in assignments late. Such resources and accommodations are necessary to ensure that survivors can continue their college educations in the aftermath of sexual assault.

Investigating and trying sexual predictors is a complicated process. Given the difficulty of investigating and trying these cases, the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network estimates that only six out of every 1,000 reports will result in jail time for the perpetrator. Even when a rapist is convicted, it is a lengthy process that oftentimes takes several years. For these reasons, college administrators should reserve the right to remove accused sexual predators from their campuses if there is sufficient evidence to do so, and they deem it appropriate. This will ensure the physical safety of the victim as well as of other students on campus.

Ultimately, the justice system and schools must play different roles in handling sexual assault cases that take place on college campuses. Members of law enforcement who are not affiliated with the school should be held responsible for collecting evidence, trying the case in court and enforcing the appropriate legal punishment. Colleges, on the other hand, should be held responsible for ensuring the emotional and physical well-being of their students in the aftermath of sexual assault. Both of these roles are necessary for making college campuses, and society, safer.