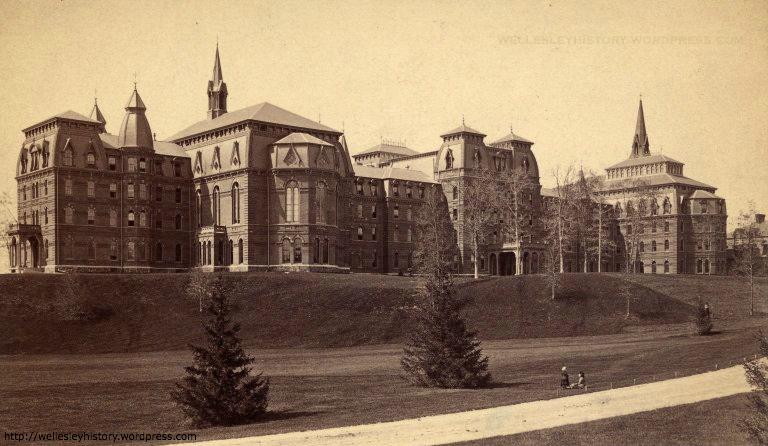

In the fall of 2017, Postdoctoral Scholar in Anthropology Elizabeth Minor ’03 and her students began an archaeological dig at the site of the former Wellesley College Hall, which burned down in 1914. The group had to stop digging once the ground became frozen last year. This past summer, however, Minor and the students enrolled in her anthropology course, “The Archaeology of Wellesley”, managed to uncover many more items lost in the fire.

Minor first began digging around Claflin Bakery and the Lake House parking lot in the fall, but she closed those areas as the group did not find many significant objects. She then redirected her attention to Tower Court.

“It was very difficult to get through. There were a lot of rocks in the top 40 centimeters, so we got about halfway down, and the ground was freezing, so we stopped,” said Minor.

By that time, Minor had started to think about creating a course during the first summer session that would continue the excavation.

“We found so much more in the summer! Part of archaeology is…you never know what you’re going to find until you dig,” said Minor. “From what we had seen before, we knew that the courtyard had the highest concentration of artifacts, and we found pretty much immediately that we had stopped just above the layer that the debris from the fire was.”

No former experience was required to enroll in Minor’s summer course. In addition to those who were registered, many other visitors and volunteers decided to help over the summer, such as the Davis Museum interns and staff from the Clapp Library. They worked from 8:30 a.m. until 1:30 p.m., three days a week.

Both Rachael Tao ’19 and McKenna Morris ’21 had been in other courses taught by Minor, so they knew about the College Hall project beforehand. Both of them felt so drawn to the work that they seized the opportunity to continue the project over the summer. Most of the class period was spent digging and sifting smaller objects, but there were other tasks as well.

“Keeping meticulous records is a fundamental part of archaeology, so a good portion of our day was spent measuring and recording depths, cataloging soil color and texture, photographing the units and processing finds,” said Morris.

Once the group reached a point about half a meter down from the surface, they started finding scorched brick, ash, rusted nails, melted glass and then, to everyone’s surprise, skull fragments.

Adam Van Arsdale, an associate professor in the anthropology department, was the one who identified the fragments through sifting. Though they were small—two the size of a quarter, and one the size of a silver dollar—he immediately recognized them as fragments of human skulls.

The fragments were found in the ash layer, but Minor knew that they did not belong to anyone living at the time, because according to historical records no one had died in the fire. They also knew that they did not come from an early burial site, because of the way the fragments were bisected.

“We could tell it was an anatomical specimen from the early College Hall natural history collection. There is an archival picture from the late 1800s of students looking at a similar skeleton in one of the classrooms,” said Minor.

In Massachusetts, if you’re excavating an area and come across human remains, you must report them to the police. The team talked to both the campus police and the town police, who turned the fragments over to the state archaeologists, but Minor hopes to eventually get them back for further study.

Though the skull fragments surprised Minor and her students, they were not the only interesting finds.

“The randomly preserved garbage is more informative in that way, because then you see what kind of activities people were really up to,” said Minor.

Minor, Morris and Tao were all amused by the sardine can key they found in Tower Court. Since students at the time were not allowed to have food in their rooms, the key implies that someone was sneaking in sardines.

“It shines a fun light on the students from the pictures of that era, who otherwise look very serious and stoic when they pose for the camera,” said Tao.

In addition to Tower Court, the group also excavated around Severance Hill during the second half of June, which is actually where they found the highest concentration of objects. These include minerals and geodes, likely from a geology lab, and a glass bottle stopper.

Minor plans to pick up where she left off at Severance Hill this fall. She will have a few dates in October dedicated to digging, which will be open to the community. Interested students should contact her if they’d like to take part. The students in Minor’s fall anthropology class will curate an exhibition of the project either in the Clapp Library Archives or in one of the display cases at Pendleton East by the end of the semester.

Both Tao and Morris were disappointed that their summer dig had to end where it did.

“We found more objects in the last two days of our excavation than we did the entire summer, and it was frustrating knowing that we would have to stop right when we had finally reached the heart of the fire,” said Tao.

Though Morris felt a similar frustration, she also felt the excitement of not knowing what she would uncover in the future.

“The best part about participating in a dig is the knowledge that today could be the day that you uncover something great,” said Morris. “The excitement you feel when you get a glimpse of something in the dirt that maybe looks like it could be something…there’s nothing like it.”