Wellesley students have participated in the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) at MIT since 1974, which allows students to train to become military officers while they are in college. Today, they commute to MIT for their training, along with members from Harvard, Tufts, Endicott and other colleges in the area.

Wellesley does not have its own ROTC battalion. According to the financial aid statement on the college’s website, “ROTC admission criteria conflict with the nondiscrimination policy of Wellesley College.”

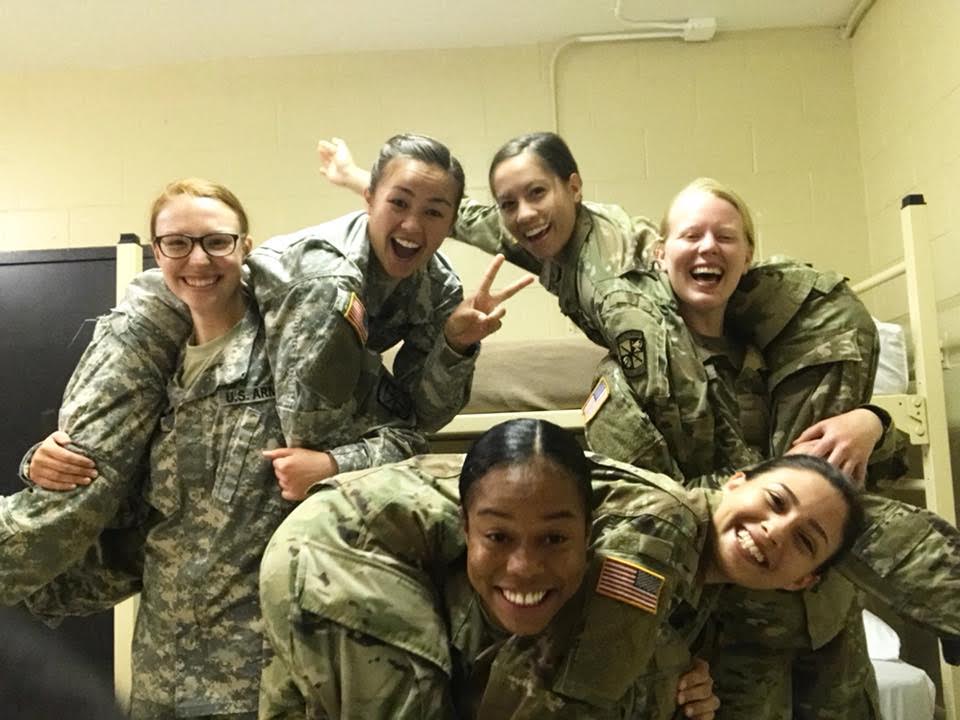

Some Wellesley students who participate in ROTC reflected on why they chose to join, how it might affect their career trajectories and if it has affected or connected with their political beliefs.

For Jessica Schuyler ’19, ROTC wasn’t originally part of her plan.

“In high school, I was dead set on applying and going to the military academy at West Point. I didn’t really see other schools until I got my rejection from them,” Schuyler said.

She became interested in Wellesley when her best friend from high school applied and told her some of the things that she loved about it. After learning more about the college, Schuyler thought she might find some of the things she had liked about West Point: “a supportive, strong community of women, rigorous academics, intelligent professors and a community like no other.”

Caroline Bechtel ’17 knew that she couldn’t have afforded Wellesley without ROTC, so she joined for the scholarship. For Emma Carter ’19, the decision to join ROTC wasn’t as important as the decision to stay. She said that she called the unit on a whim, missing the camaraderie and work ethic of her high school sports teams.

“I choose to stay because of the people and the mission,” said Carter.

Schuyler, Bechtel and Carter all chose Army ROTC over other branches, like Navy or Air Force. Schuyler saw it as a good branch where she could explore her options, and also the easiest branch to join at Wellesley because there were no senior cadets in other branches who she could look to for guidance. Bechtel felt drawn to the army’s history of leadership and service. Carter also liked the history of the army and cited the ability to make a direct impact.

“Being the ‘boots on the ground,’ having such a direct combat role was extremely attractive to me because I’ve always been a doer,” said Carter.

ROTC has a relatively small presence on Wellesley’s campus, and students commented on their somewhat unconventional decisions to both attend a historically women’s college and join the military. Schuyler found herself drawn to the strong community networks of both the army and Wellesley. She sees her position as a Wellesley woman in ROTC as a chance to break down barriers for other women.

“One thing that many women I have heard speak as trailblazers for women in the military is their emphasis to doing your job, and doing it well,” said Schuyler.

She hopes to use the confidence she gained at Wellesley to further this attitude among her peers and other soldiers.

Bechtel didn’t see a conflict between the choices.

“I never saw Wellesley and the military as at odds. Wellesley’s purpose — to educate women who will make a difference in the world — aligns perfectly with my goals in the military, which are to make a difference in the lives of soldiers and contribute to the sustainment of a rule-based and democratic neoliberal world order,” Bechtel said. “ROTC was incredibly empowering for me. Participating in ROTC pushed me outside of my comfort zone and prepared me for a future in the real world.”

Similarly, Carter also said that she hadn’t considered the potential juxtaposition of the military and Wellesley until she was participating in both; she sees the military as a way of fulfilling her take on Wellesley’s goal of empowering women.

Heather Gluck ’20, a student unaffiliated with the ROTC, said that feeling empowered by individual military membership doesn’t justify the potential harm.

“It’s not a question of whether or not joining the military empowers you, it’s about the death, destruction and imperialism that you participate in by joining the military. If you want to get empowered, do community organizing, fight for the lives of the immigrants being attacked by ICE at our southern border, do some work that helps people,” Gluck said.

While Wellesley ROTC members described the military as officially apolitical, they all noted some backlash or negative reactions they felt on campus. In Bechtel’s experience, most students have been supportive, and negative reactions are usually implicit rather than said outright.

Bechtel remembered once in class she felt like her Wellesley identity was called into question as the professor started a discussion about the militarization of college campuses after the “Sleepwalker” statue was dressed in military apparel. During the discussion, Bechtel was still wearing her physical fitness uniform because she hadn’t had time to change between her workout and class.

Schuyler commented that there have been times that ROTC has felt pushback from both students and administration. She finds that by encouraging dialogue and making connections with non-ROTC students, people tend to be more open-minded.

Negative reactions led to some ROTC students at Wellesley choosing to hide their affiliations. Bechtel spent her first few years hiding, then eventually became more willing to talk about her position.

“I grew proud of it when I realized that most negative reaction to the military is misguided; civilian decisionmakers create policies, and the military only executes those policies,” said Bechtel.

Gluck doesn’t see the U.S. military as apolitical, and takes issue with that claim.

“We wouldn’t call the Iranian military, the Chinese military or any other military in the world apolitical, so why would we make that claim about the US military? The fact that the US military doesn’t decide foreign policy is not relevant, because they enact that policy,” Gluck said.

Carter, on the other hand, expressed thoughts about misconceptions among civilians who ask her about current wars.

“I respond the military does not choose to go to war, you choose. The politicians you elect send us abroad,” she said, emphasizing her hopes to improve the institution from the inside and develop greater diversity.