Wellesley College, along with the town of Wellesley, is built on unceded land belonging to the Massachusetts people, who since the 1600s have seen their territory taken away by force by European colonizers. This history of violent colonization and land theft is what is now widely agreed upon by historians — but it isn’t one that is often taught in our schools, or acknowledged in the popular narratives of how the United States came to be. For the over 37,000 Native American people living in this state, the yearly celebration of Columbus Day is often a painful reminder that a genocidal historical figure is being celebrated, while the Indigenous history of this place and these people is being forgotten.

A coalition in the town of Wellesley is aiming to change that, by petitioning the town to officially recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day instead of Columbus Day.

Joan Aandeg, who is an Anishanaabe woman of the Lac Courtes Oreilles band of Ojibwe people, was disappointed when, last year, she saw ‘Columbus Day’ labeled as a day off on her first-grade daughter’s school calendar in Wellesley school district. She had recently come back from a healing gathering at Standing Rock — the site of the 2016 Dakota Access Pipeline protests, in which Native American protestors faced off against the U.S. Army in an attempt to stop an oil pipeline from being routed through sacred Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Lands — and had reconnected with her own Native American heritage there.

“It was really transformative for me. It really solidified what I had been learning and what I had been feeling about the importance of this Indigenous movement,” Aandeg said. But then, when she got back to Wellesley, she saw that her daughter’s school calendar didn’t recognize Indigenous people, but instead had a day off dedicated to a man who was to blame for their genocide.

“I was gravely concerned that my daughter not be inculcated with the colonial myth that Columbus ‘discovered’ America.” Aandeg said. “I feel deeply the injustice of a colonial power decimating the populations of this land, dispossessing the people of their homes and life ways, depriving them of their languages and their cultures … and then teaching their children that the first genocidal maniac to land on our shores was an adventurer and hero who ‘discovered’ what was subsequently stolen from us.”

So, Aandeg joined forces with Michelle Chalmers, president of the local organization World of Wellesley, which organizes events promoting awareness and acceptance of diverse communities within Wellesley. But as the two of them planned, someone began acting faster than them: twelve-year-old Annie Hodge, who published an op-ed in the local newspaper the Wellesley Townsman, declaring that based on what she had learned in her social studies class, Columbus Day should be replaced immediately with Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

Hodge joined the World of Wellesley committee working on the project, with permission from her parents, and the petition which is now circulating to recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day in Wellesley was sent out. To date it has collected over 200 signatures, in large part due to Annie Hodge’s father, Wellesley College Professor of Russian Thomas Hodge, who sent it out to Wellesley students in an all-school email.

“I think if it’s that clear to a twelve-year-old that Columbus Day is a misguided placement of our respect and honor for the past, we should take steps to remedy that,” Thomas Hodge said. “So now I’m essentially working as an assistant for my daughter, helping her to spread this signature drive.”

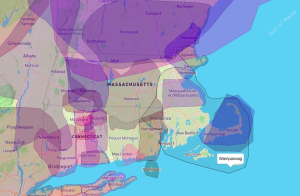

Wellesley is not the first town to take up this cause. Many municipalities in the area have officially switched to celebrating Indigenous Peoples’ Day in recent years, including Brookline, Cambridge and Somerville. Some here at Wellesley College hope that the college will follow the town’s lead in choosing to recognize Indigenous people rather than their colonizer. Kisha James, who is the leader of the Native American Students Association here and an enrolled member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gayhead Aquinnah and the Oglala Sioux Tribe, has worked on Indigenous Peoples’ Day campaigns before with her mother and hopes to bring that here, too.

“Indigenous Peoples Day is about more than a name change,” James said. “It’s a refusal to allow the genocide of Indigenous peoples to go unnoticed, and a demand for recognition of Indigenous humanity. It is also a way to correct the harmful myth that Columbus ‘discovered’ America (news flash: you can’t discover something already inhabited by millions of people) honor Indigenous peoples and begin to correct some of the countless atrocities committed against Indigenous peoples of this country.” James said that, even here at Wellesley, the prejudices created by years of narratives like the one surrounding Columbus day are noticeable — and that the historically inaccurate things people have told her about her own heritage demonstrate the need for an Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

“I have been told by people on this campus that what Columbus did was acceptable because ‘Native Americans were scalping and eating each other anyways,’ and that we were ‘savages’ who needed Christianity. I have also heard many people make excuses for Columbus, calling him a ‘product of his time,’ and some professors have told me to ‘stop trying to revise history,’”James recalled. James asks students on campus to sign the Wellesley Indigenous Peoples’ Day petition, and to sign the Wellesley College version of that petition that the Native American Students’ Association intends to create.

Many other colleges have chosen independently of their municipalities to celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day in recent years, including Cornell University, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Harvard University and Tufts University. James hopes Wellesley will follow in their footsteps, and that, in addition, the College will release an official land acknowledgement, which will acknowledge that Wellesley is built on stolen and unceded Massachuset land.

Indigenous Peoples’ Day, Michelle Chalmers of World of Wellesley says, is only a first step. “We understand that this is a symbolic gesture,” she said. “This is something that will change a couple of calendars in the town. But we want it to be more than that.” So, per Joan Aandeg’s suggestion, the day will be spent on Indigenous cultural education and environmental clean-up projects. Recognizing Indigenous ways of relating to the Earth, Aandeg believes, is not only a way to paint a more accurate picture of history, but a way forward in a future of climate collapse.

“It is a time of planetary, ecological crisis,” Aandeg said. “Climate change, mass extinctions, ecosystem collapse — all caused by humans living out of balance. I don’t know how we are going to fix it, but I do feel that regaining our connection to the Earth, living in respectful relationship with all life, is necessary if we are to survive this crisis.”

The Indigenous Peoples’ Day recognition petition can be found online at www.worldofwellesley.org.